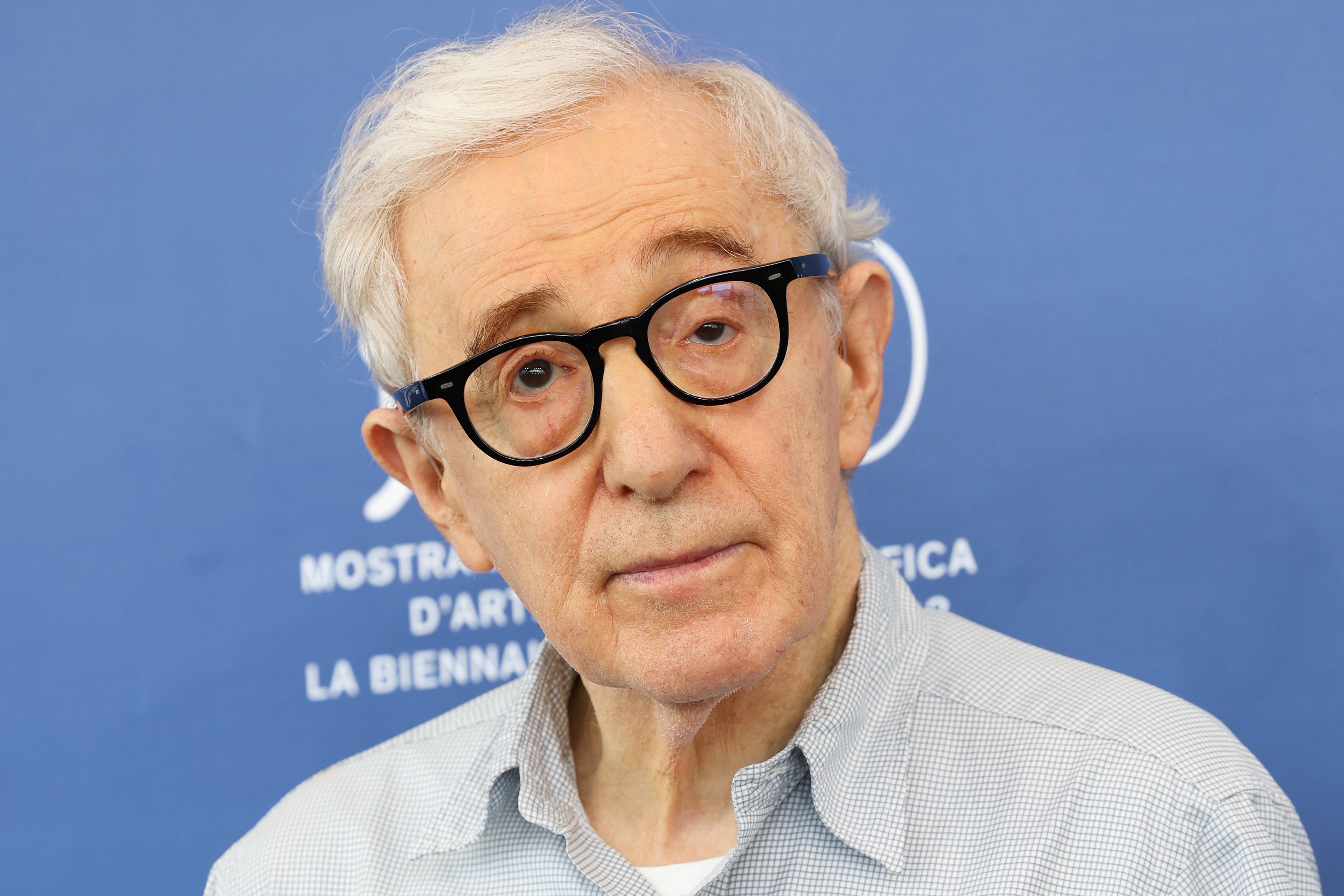

If someone were to pluck What’s With Baum? from a bookshelf without knowing who authored it, what would they make of it? They might think that it’s a slight, forgettable novella detailing the midlife crises of a neurotic, vaguely lecherous writer – a John Updike plot, minus the magical clarity of Updike’s prose. A book that gestures towards provocation, but does not commit. In other words: they’d think it straightforwardly unremarkable. But, of course, we do know the author of Baum. And that author is 89-year-old filmmaker Woody Allen.

Baum is Allen’s first novel, written at a time when his prolific film career – reputationally hobbled by resurfaced sexual abuse allegations and a long run of incidentally dismal movies – has seemingly tailed off. (Allen has repeatedly and vehemently denied the allegations of abuse by adoptive daughter Dylan Farrow, and was previously cleared of charges following an investigation.) He has yet to film anything since 2023’s French-language melodrama Coup de Chance (a real sacre bleu of a film), his last American venture being the excruciating Rifkin’s Festival (2020). Baum is not, however, Allen’s first foray into fiction; his writing career dates back to 1971’s stories and essay collection Getting Even. Joke-heavy, unserious and leaning heavily into the absurd, that book was in keeping with the tone of Allen’s early comedy films; in much the same way, Baum feels of a piece with his more recent directorial efforts. It has the same comic leadenness, the same lapses into melodrama, the same stubborn cultural atavism.

The novel’s narrator, Asher Baum, is an archetypical Allen protagonist – an erudite, libidinous nebbish. Baum, Allen writes, is a man “born into loneliness the way one is born into autism”. He is a writer of limited renown, overshadowed by the success of his stepson Thane, a supposed literary genius. (There’s something unsubtly Oedipal about Baum’s family unit: Thane is perhaps a little too close with his mother, Connie, while exchanging with Asher only cold animosity.) Early in the novel, Baum is informed that a damaging newspaper interview is about to reach publication. In it, a younger female Japanese-American journalist paints him as a predator, alleging that he tried to forcibly kiss her, made a sexual pass at her, and then, while falling over, grabbed her breast. In Baum’s slightly unconvincing retelling, there were benign explanations for all of this.

In between hypochondriacal musings, Allen spends much of Baum dancing around taboos – including the messy intersections of family and romance. Near the beginning of the book, Baum says that he suspects his brother of sleeping with Connie. A previous marriage was ruined when Baum had an affair with his then-wife’s identical twin. At one point, Connie remarks of her doted-after son: “Is it any wonder every woman falls in love with Thane? I could if the law allowed.” A good chunk of the book is also devoted to Baum’s infatuation with a beautiful younger woman named Sam – who happens to be dating his step-son.

All of this is somewhat tongue-in-cheek, a purposeful provocation. But Allen, who dedicates the book to his wife Soon-Yi Previn, the adoptive daughter of his former partner Mia Farrow, does not help himself. Women are referred to multiple times as “creatures”. Baum describes his wife in one instance as a “complex thoroughbred”, in another as akin to “the wicked queen in Snow White, a nasty babe but hot”. It’s all a bit wince-inducing, even if it weren’t coming from Allen’s pen. There are times when Baum hints at becoming a sort of bitter treatise on cancel culture – “You know what craven sheep people are,” Asher remarks at one point – but, mercifully, shies away from this.

Like much of Allen’s late film work, Baum is compulsively exophoric, name-checking as many of the writer’s cultural passions as possible. George Gershwin; Hannah Arendt; Buster Keaton; Cole Porter; Ingmar Bergman: the references come thick and fast, but add little to the story, while also reaffirming Allen as a man out of time. But for a singular reference to cinema tickets now costing $15, Baum seems stuck in a perpetual American midcentury.

None of these problems are helped by Allen’s prose style – inelegant throughout, and sometimes abjectly clunky. And yet, in brief moments, Allen does touch on something worthwhile. Baum is no work of autofiction, but there is a lot of its author in there, unhidden – and at times, he seems, through Baum, willing to engage in ruthless self-scrutiny. By the end, Baum is an utterly unsympathetic figure, a befuddled, vindictive also-ran. “You are not Dostoyevsky,” a publisher tells the character towards the end of the novel. “Though it is clear you would like to be. And even he had great humour. As did Kafka. But why talk about geniuses. You are not one. I’m sure you realise that. I don’t mean to imply that you don’t have your own limited gift, occasional flashes of wit and imagination. My candid opinion is that you have too much anger and it is another reason your writing becomes dull.”

Whether or not Allen is intentionally addressing his own writing here, these are words that ring true while reading Baum. The shame is that Allen was once a great artist, one whose wit and imagination went far beyond flashes. But Allen is by this point steeped in artistic mediocrity – a creative rough patch that has lasted the better part of three decades. Ultimately, Baum is just another shrug to throw on the pile.

‘What’s With Baum?’ is published by Swift Press; out 25 September