I feel like a fraud when I give the address to the taxi driver. It’s silly, really, but I can’t help it – I mumble the name “Complete Fertility” under my breath like an awkward teenager asking to be dropped off at the sexual health centre.

The reason for my embarrassment? I’m not the “typical” client associated with a fertility clinic. I’m neither pregnant nor trying to get pregnant. I’m not here with my partner, because I don’t currently have one. I’m simply a single, 38-year-old woman staring down the barrel of my fast-closing fertility window, wanting to feel like I can exercise some control around what feels like the biggest life choice I’ll ever – or never – make. Motherhood.

As a woman, I’ve found that the majority of life thus far seems to have revolved around my womb and its potential. In the first post-puberty years, periods were the irksome monthly event that prevented the wearing of white jeans and caused panic attacks about bleeding through gym shorts in PE. In my twenties, they morphed into something more closely resembling a friend – a sign that, thank God, I had once again swerved unwanted pregnancy, a fear so ingrained through overzealous “sex ed” classes that I felt a surge of relief even during spells of celibacy.

But then there was the inevitable tipping point that hits many women in their thirties – when we go from worrying about accidentally getting knocked up to wondering whether it’s even possible.

For a good few years, I didn’t think I wanted children. Then I found myself gently tugged into the grey area – ambivalent, unsure. Maybe I could be tempted if I met someone who really wanted them. And then, for reasons I still can’t fathom, this year I felt myself becoming actively drawn towards the idea of becoming a parent – quite possibly my body’s last-ditch “Hail Mary” attempt to get me up the duff. No definitive decision had been made, but it started to occupy my mind more and more.

When you’re not married or in a committed long-term relationship, the issue begins to weigh heavily on dating decisions. Should you ask someone their views on starting a family within the first five minutes of meeting them? Issue a quiz to determine whether they’d make a good parent? Request a copy of their bank statement to check that they can help to provide for any future progeny – or a full medical history, Gattaca-style, to ensure good genes for this imaginary offspring?

Yes, this may sound crazy. It is crazy. But female biology, with its inbuilt hard deadline for baby-making in the form of the menopause, can feel like it necessitates such blunt candour.

Unlike males, females are born with all the eggs we’re ever going to have. That means our eggs are as old as we are – they age, just like the rest of the body. Every month, from puberty onwards, a batch of them mature and go head to head, with only the best one selected to be released when we ovulate. The rest of that cycle’s contenders get discarded. The older we get, the fewer eggs we have to take part in this monthly battle, and the less likely it is that the top dog is of sufficient quality to create a healthy baby.

A woman in her twenties will have around 20-30 eggs competing each month, with one out of every four to six likely to be “normal”, resulting in two to three good eggs each month. By the age of 40, the average number of competing eggs has dropped to 10-12, with a likelihood that one in 15-20 will be normal – resulting, some months, in there being no good eggs. The chance of conceiving drops accordingly (and that’s before we even get into the male side of the equation: sperm quantity and quality also decrease with age).

Many people are ignorant of the most basic science behind reproduction; we blithely assume we’ll be able to get pregnant at the drop of a hat until proven otherwise. A survey of 2,000 people by Complete Fertility revealed that 78 per cent of respondents were completely unaware that heterosexual couples over the age of 35 have less than a 30 per cent chance of natural conception on their most fertile day each month.

Meanwhile, we are leaving it later and later to have children, and the fertility rate for England and Wales has plummeted to a record low after falling for three consecutive years, according to recently published Office for National Statistics data. More women than ever before are reaching the age of 30 without having become mothers; the average age of new mums in England and Wales climbed to 29 in 2024; and the standardised mean age of mothers has hit 31 – the highest since records began. This is reflected in fertility treatment: the average age of women starting IVF for the first time passed 35 last year, and the number of single women in the UK undergoing solo treatment more than tripled between 2012 and 2022.

Women want the ability to act before things feel out of their control

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that more of us are also wanting to get our fertility checked, regardless of our relationship status. Hertility Health, which offers at-home hormone and fertility testing kits, has seen an increase in women and people assigned female at birth using its services, “not always because they are ready to conceive, but because they want to better understand their reproductive health and future fertility options”.

In its annual ReProductive Report, based on data from 610,654 women, 142,048 respondents listed “just curious” as their primary reason for completing the brand’s online health assessment. “That includes many women who simply want clarity about their reproductive health before it becomes urgent,” according to a spokesperson.

“Clarity” is a motivating factor for Lily*, 35, who recently found herself single again after getting out of a nine-month relationship. She knows that she wants to be a parent, but has no idea whether it can happen naturally. “I’ve spent years in conflict with my body, tangled in a negative relationship with food, exercise, body image struggles and eating disorders, and consequently, I carry guilt about the damage that I am likely to have left behind,” she says. “As I move out of my mid-thirties, I feel a growing urgency to finally understand what’s happening inside my own body – something so personal, yet still such a scary mystery to me.”

Lily went through the NHS and was forced to lie to get a fertility health check. Typically, only heterosexual couples are referred for fertility testing once they’ve been trying to conceive naturally for a full year (although this timeline can be speeded up for women aged 36 or over). It feels like a strangely antiquated approach when even the British government is spooked enough by the declining birth rate to be encouraging us to have more children.

Those who are in heterosexual relationships are turning to testing, too. Sarah*, 31, is engaged; she and her fiance know they want kids in a few years, but not yet. As this will take them into their mid-thirties, they both privately paid to get tested “to see if there’s anything we might need to do before that time, such as freezing eggs. After all, knowledge is power.”

Sarah calls it a “positive experience”; a consultant confirmed that both she and her partner appeared to be fertile. “We are now feeling very confident in waiting a little while longer until we feel ready to start a family,” she adds. “It’s worth the money for the peace of mind, in my opinion – though I suppose it’s not a guarantee that I’ll get pregnant in a few years’ time.”

As Hertility puts it, increasingly women “want to be proactive – seeking the information they need to take potential issues into their own hands. They want the ability to act before things feel out of their control.”

This could certainly sum up my mindset. I’ve never tried to conceive, nor had the merest glimmer of a pregnancy scare, and realised I was flying blind – attempting to make big life decisions without any of the relevant information to back them up. Shutting down a potential relationship with the guy of my dreams because he wasn’t interested in procreating only made sense if I was able to procreate, didn’t it? Surely, heading into this next chapter of life might feel less stressful if I were armed with all the available facts?

As I move out of my mid-thirties, I feel a growing urgency to finally understand what’s happening inside my own body

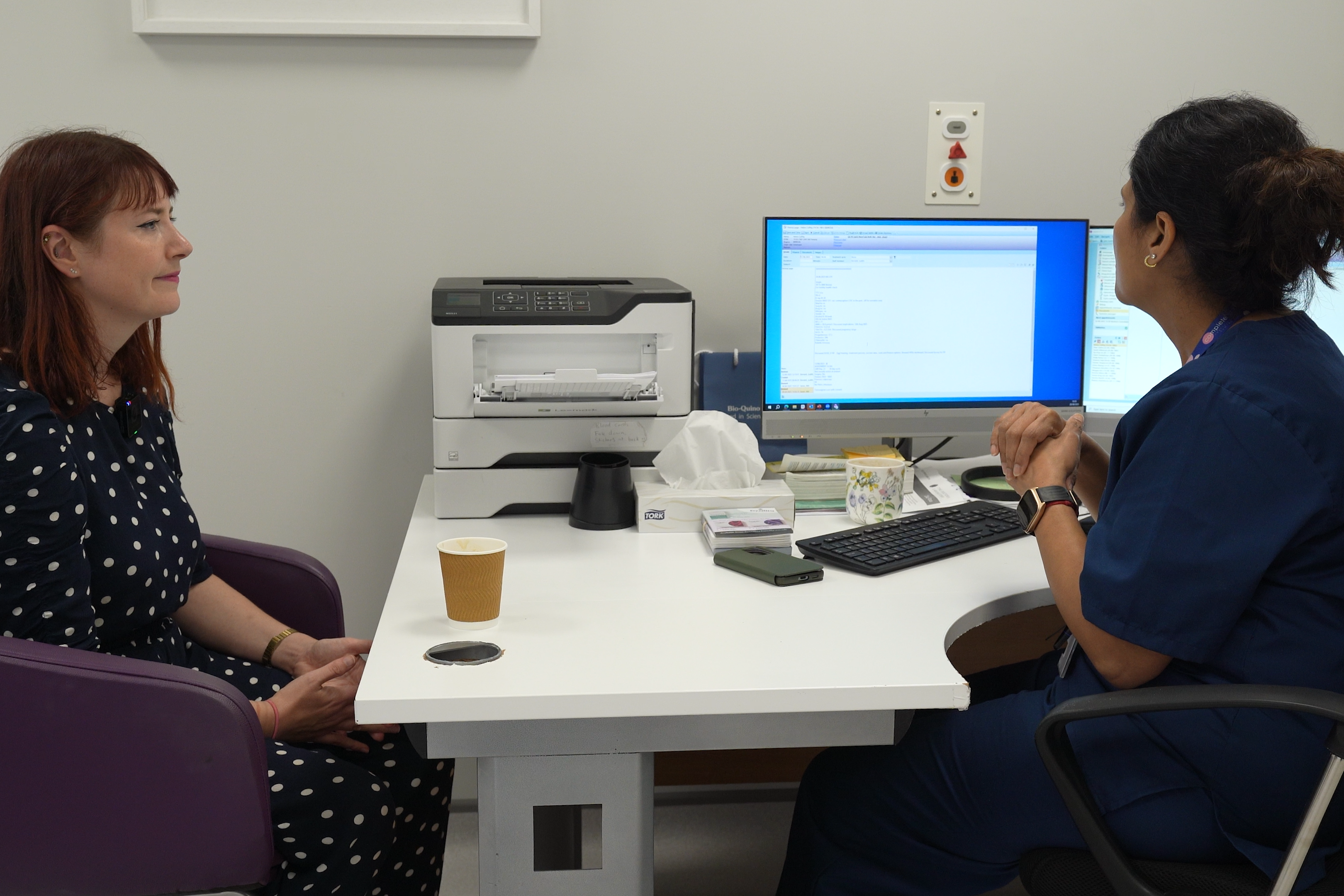

Hence my trip to Complete Fertility near Winchester. The clinic offers a full range of fertility services, from testing, to egg and sperm freezing, to IVF, IUI and ICSI. A standard female fertility health assessment costs £495 for an Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) blood test, a transvaginal scan, and a consultation with a specialist. The premium package, at £825, also includes a test on day 2-4 of your cycle to measure levels of follicle-stimulating hormone/luteinising hormone (FSH/LH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), T4 hormone, vitamin D, and prolactin, as well as checks for rubella and chlamydia, plus a test on day 21 of your cycle to measure progesterone. I opted for the latter for a fuller picture.

The blood tests have to be sent off for analysis, but I can see the results of the transvaginal scan on screen in real time for myself. This procedure involves inserting a specialised probe into the vagina, which uses sound waves to create images of the uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes. The sonographer checks the shape of the womb – all normal – and for signs of issues like scarring, fibroids, cysts or endometriosis. And then, crucially, she counts the number of antral follicles visible in each ovary.

These small, fluid-filled sacs each contain an immature egg that will come to maturity that month – it’s from these that one will be crowned the winner and released into the fallopian tube. How many there are gives a good indication of ovarian reserve – the number of eggs you have left – and the average antral follicle count (AFC) goes down as you age.

People in my age bracket can expect an average of eight to 15 across both ovaries. As it turns out, I have more than might be expected, with 18 visible on one side and 13 on the other: 31 in total. “That’s a very good number for a 38-year-old,” the sonographer says encouragingly, and I feel a little thrill of unearned pride.

AFC results are frequently mirrored by blood test results, and so it is in my case. When I sit down with Complete Fertility’s medical director, Mili Saran, she tells me that everything looks largely positive. The battery of blood tests have shown that I’m still ovulating and have a healthy egg reserve for my age, indicated by my high/normal AMH level. But what I really want to know – the actual quality of those remaining eggs – is impossible to say. There’s no magic test to tell whether they’re A* students or total slackers; whether they’re more dregs than eggs. “We unfortunately cannot test for that,” says Saran. “Unless we get them under a microscope – and even then, it’s not conclusive.”

She asks me whether I know what I want to do: sit with the results and think about next steps? Freeze my eggs? Go straight to exploring fertility treatment using donor sperm? I realise I haven’t a clue. Part of me always assumed that my ovaries would be a dusty, barren wasteland, based on nothing more than the fact that I don’t feel particularly maternal about other people’s babies. Though devastating, there would have been a kind of relief in that – the choice being out of my hands. The backbreaking heft of the decision taken off my shoulders and laid gently at my feet. Discovering the opposite has raised more questions than it’s answered. Massive, earth-shattering questions like: could I envisage pursuing motherhood alone? Aside from the financial and practical obstacles, would I really be up to the task? Could I really make a good mother?

I don’t immediately have the answers, yet I don’t regret facing one of life’s biggest unknowns head on. Knowledge might not quite feel like power, but it certainly feels more empowering than passively waiting for the motherhood question to become a full stop.

*Names have been changed

How to tell when your child is being bullied – and how to help

‘This trade-off isn’t worth it’: Working moms are leaving their jobs in droves

Tia Mowry sparks debate after saying it isn’t parent’s job to ‘make kids happy’

The five ultra-processed food ingredients to avoid – and what to buy instead

The best and worst outfits celebrities and players have worn at the US Open 2025