Spirited Away came out in 2001, when I was 8. After watching it in a Japanese cineplex, I stumbled out into a wall of late-summer heat, shaken by what I had just seen: the grotesque transformation of parents into pigs, the vomiting faceless monsters, the evolution of a sniveling girl to a brave heroine. The way a dragon could be a boy magician and also a river, how the story seemed held together by association and magic. Yet I also felt the compulsion to return to the cool dark, to plop down in the upholstered seat and submerge myself in the director Hayao Miyazaki’s world, taking it in again and again.

That summer was my first time back in Japan since my family had moved to the United States earlier that year. Everything felt fraught and fragile. After seeing Spirited Away, I shifted my anxiety onto the film, somehow certain that I’d never watch it again, at least not in the U.S. This was an era before Netflix, when we were lucky to find a battered VHS copy of Studio Ghibli’s Castle in the Sky at the local rural-Illinois Blockbuster, Anna Paquin’s twang dubbed over Sheeta’s voice.

Thankfully I was wrong: 14 months later, Spirited Away was released in the U.S. Showing in just 26 theaters, it made a measly $450,000 in its opening weekend with minimal promotion. By comparison, the film spent 11 weeks at the top of the Japanese box office. But months after its U.S. premiere 20 years ago, Spirited Away became the first and only Japanese film to win Best Animated Feature at the Oscars. The once-niche movie became a sleeper hit. By the end of 2003, the film had played on more than 700 American screens, pulling in more than $10 million.

[Read: Hayao Miyazaki and the art of being a woman]

I never saw Spirited Away in a theater again, instead rewatching it in the homes of friends and American family members. One memorable winter break, I played it on loop in my parents’ basement, dozing off and waking up when the film ended and the DVD menu popped up. Because the movie gained recognition well after its initial theatrical release, by the time Americans wanted to see it, they already had the option to rent or buy it on VHS and DVD. I could always count on seeing Chihiro gazing plaintively at me from video-store shelves, or on being able to reference Miyazaki in casual conversation as “you know, the guy who made that movie Spirited Away.”

Still, between Spirited Away’s video-store ubiquity and today, 18 years passed during which Blockbuster went out of business and the only way to watch Miyazaki’s films was to buy a physical copy. Now Americans can see Studio Ghibli films on HBO Max whenever they want. When I first read that the streaming platform had secured the rights to all Ghibli films, I emailed the article to my husband with the subject line “!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!” Thus began a new era of the Studio Ghibli rewatch, not as an occasional treat but as a commonplace ritual, and I’ve learned that these jewel-like films take on a new shine when you revisit them. For me, rewatching Spirited Away isn’t an experience of settling into a soothing story; rather, each viewing is an opportunity to notice new symbols and to consider new narrative possibilities.

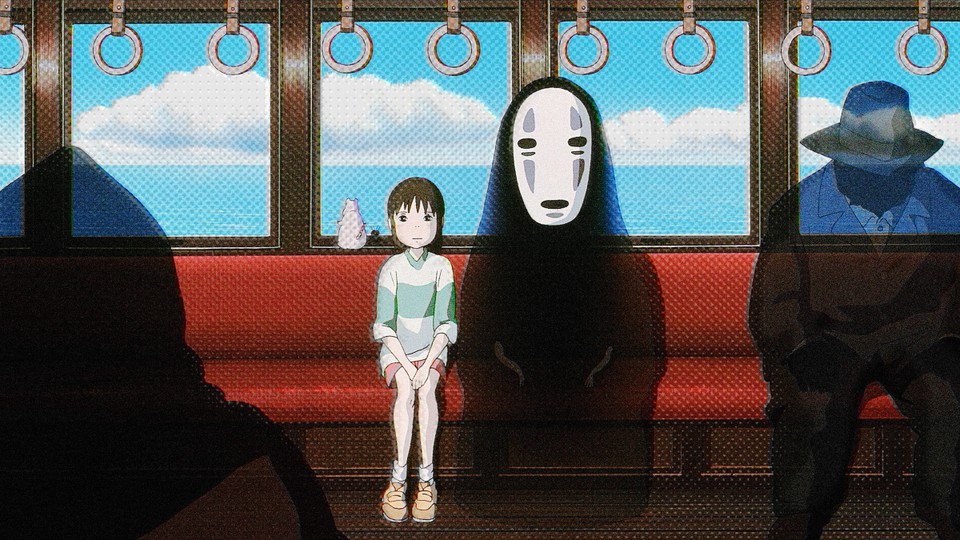

Twenty years ago, I would’ve been able only to summarize for you the main plot points of Spirited Away: A girl finds herself in a spirit world and must work at a bathhouse operated by a witch in order to save her parents, who have been turned into pigs. I could probably also tell you about the individual moments that burned themselves into my mind: the scene where Chihiro, given the new name Sen, sobs as she eats onigiri underneath tall flowering bushes, overwhelmed as the reality of her isolation sinks in. Or the sequence where No Face, a dark spirit who follows Chihiro on her journey in the spirit world, regurgitates a tidal wave of black goo. Or the gorgeous scenes that take place on the mysterious train line, pensive, mournful, and somehow evocative of the experience of crossing the river Styx after death.

But only now can I tell you about the texture of the world Miyazaki created—for instance, the flickering neon signs advertising pork on the lane where Chihiro’s parents first turn into hogs. During one recent rewatch in a double feature with Howl’s Moving Castle, I noticed the choice to dress Yubaba, the witch who puts Chihiro to work, in gaudy Western attire despite her Asian-bathhouse surroundings, similar to Miyazaki’s later rendition of Howl’s Witch of the Waste; in both cases, he uses the women’s occidental stylings to highlight their tasteless greed. On another occasion, I realized that Rin, the young bathhouse worker who becomes Sen’s friend and guide, shares a resemblance to Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke and Satsuki from My Neighbor Totoro—they all fit the Ghibli big-sister archetype. Only in rewatching did I start to see and appreciate the connections between characters in the Miyazaki Cinematic Universe.

[Read: Remembering animation’s legendary Isao Takahata]

Without putting Spirited Away on in the background as I folded laundry, I would never have noticed that the film begins not with an image or a title card but with a sound: Joe Hisaishi’s unresolved arpeggio sets the stage before Miyazaki even allows us to see his animation, asking us to consider the uncanny, alluring world we’re about to enter with a moment of music. In a recent episode of the podcast The Stacks, the writer Ingrid Rojas Contreras talked about hearing repeated stories from her mother: “When somebody tells you a story over and over again, the details of the world-building start to emerge.” So, too, does Spirited Away change upon being revisited, from an interaction with narrative and plot to a momentary immersion in a fantastical, yet somehow familiar, world. Now, as an adult, I recall my childhood horror at No Face, even as I feel intrigued by his blank, smiling visage. I revisit these past selves scattered across the film, greeting them as I notice new things and delve deeper.

Then again, it’s a strange time to consider the staying power of animation, given that HBO Max just unceremoniously erased 36 animated shows from its platform. Specifically, I’m thinking about Infinity Train, a four-season series by Owen Dennis, each season of which follows a character who finds themselves on an endless magical train. When I first watched the series, the callbacks to Spirited Away and Miyazaki were crystal clear: There’s the Steward, a terrifying robot who resembles No Face. There’s the main character of Season 1, Tulip, a plucky but unhappy young girl trying to adjust to a major life change, just like Chihiro. And then there’s the unexplained train itself.

Even though streaming is what transformed Studio Ghibli films into objects of daily wonder for me, it now forces me to consider again the precarity of media when they depend on the whims of their distributor to exist. Infinity Train, alongside many other animated titles, was thrown into the vault as an apparent cost-cutting measure, an outcome not dissimilar to those lost years that followed Blockbuster’s closure. I watched the four seasons of Infinity Train once through, and marveled. Naively, I assumed that because the show was hosted on a streamer I’d be given some time to go back and dive into Dennis’s world, to notice the universe beyond the main story line.

Instead, I’m left with the old ephemeral feeling, anxious about something I may never see again. I wonder about the wistful train that cuts across watery tracks in Spirited Away. If I watch it carefully enough, maybe I will notice other universes it enters, even that of shows like Infinity Train. For now, I let the train car, with its burgundy seats and shadowy customers, fill my view, Chihiro and No Face staring back at me.