About two months ago, a slow fall hit rock bottom for Richard Hodgson and his son Kaleb Hodgson when a white pickup truck drove through the middle of an elk hunt on their property in far northwest New Mexico. Elk scattered, their hunting clients left, and the Hodgsons realized that the oil companies that had drilled their land for decades might not be their friends after all.

“It just drives me totally insane,” Richard said.

He’s the patriarch of three generations of Hodgsons who live on a spread he started 42 years ago in the high, dry country he loves. Richard was born and grew up in nearby Farmington but always wanted to be a cowboy in the San Juan Basin, among the region’s green and tan mesas under an electric blue sky.

As a young man he bought the ranch’s initial parcel with money made from driving trucks and working as a roustabout for oil and gas companies. In lean ranching years he’d go back to the oil patch for the money, using that to buy more land.

Today the family runs around 200 mother and calf pairs on the 5,600 acres it owns and roughly 32,000 it leases from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. And everywhere you look on that land, there’s an oil or gas well — the family doesn’t know how many. “I don’t know if we really want to know,” said Kaleb, Richard’s eldest son. “It’s kind of overwhelming, honestly.”

Kaleb said a movie crew came to the ranch a few years ago to shoot scenes for a film and loved the place — but won’t be back. Crew members told him it cost too much to digitally remove all the wells that appeared in the background.

Father and son think they have room enough to run another 60 to 100 cow-calf pairs, but recent droughts have shriveled the forage and dried up the natural watering holes. The oil and gas that come out of the ground in the San Juan Basin contribute to the changing climate that’s drying the region. This summer, the dust was so thick on the grass that it wore down the cows’ teeth. “It takes years off their life,” Kaleb said.

“Everything’s an uphill battle out here,” Richard said. “All I ask for is respect.”

Kaleb Hodgson, Luke Whitley and Richard Hodgson stand in a pasture on the Hodgson ranch. Years ago, the well tanks behind them leaked and flooded the pasture with produced water and oil.

And the family feels it isn’t getting any from its biggest neighbor, Hilcorp Energy Co. The Houston-based company is one of the largest privately held oil and gas producers in the country, with operations in nine states. In 2017 the company began a massive acquisition campaign in the San Juan Basin when it bought ConocoPhillips’ assets. In the New Mexico portion of the basin, it now operates 11,400 wells. Roughly 1,600 of them pepper the area on and around the Hodgsons’ lands.

Hilcorp and the Hodgsons are close neighbors because of a legal quirk called a split estate, under which the property rights to the surface land are separate from those of the minerals that lie beneath. The Hodgsons own the surface rights, and the federal government owns the underlying mineral rights, which, in this area, it leases primarily to Hilcorp. By law, landowners must allow subsurface rights owners to have access to those minerals. For the Hodgsons, that access takes shape in a spiderweb of roads and wells stitching their thousands of acres of pine-dotted mesas and valleys.

For years, that arrangement between the Hodgsons and Hilcorp worked — until very recently, when it didn’t.

Hilcorp did not respond to Capital & Main’s repeated requests for comment.

Over the years, relations with oil companies were manageable, if not always great.

Richard recalled his days as a roustabout and truck driver decades ago and what he called the industry’s almost complete lack of environmental controls at the time.

One example: He said that companies used natural gas to flush out newly drilled wells, then lit the polluted mixture on fire in massive flares. “This whole country at night was orange,” he said. “It was so wasteful.”

Another example: Wastewater from oil production — often called produced water and laden with hydrogen sulfide — was dumped in ditches and ponds throughout the region. “I done it. I was sent out to do it,” Richard said. He’s sure that all of the ground beneath waste pits near older wells are contaminated from that dumping.

Another example: A few years ago, he watched a neighbor’s cow drink from a puddle of filthy water pooled beneath a pumpjack. The cow stumbled off, bellowing, then fell in a ditch and died.

And another: On a hot summer day, before he could grab its collar, one of Richard’s dogs jumped into an open waste pit to cool off. The dog swam around and came out covered in grease, immediately got sick and went deaf. The dog lived for a couple of years before it was run over by a truck it couldn’t hear.

One more: In November, 2023, there was a spill at a well he could see from his front door. He worked for a whole day alongside a crew hired by Hilcorp to dig out 1,000 yards of petroleum soaked soil. “We got out of the hole, and everybody had a headache [from the fumes]. It was that dirty,” he said.

Richard said he left for a few hours. When he returned, the company had fenced off the pit and said their work was done. In April, 2024, Richard called the New Mexico Oil Conservation Division — the state’s primary oilfield enforcer — to get Hilcorp to remove more contaminated soil. Nothing more was removed, and two weeks later Hilcorp submitted a closure report to the Division, saying the company had finished its cleanup work. The Division closed the case the same day. The Division’s response read, in part, “Since the release occurred within an area reasonably needed for production operations (on-pad), the reclamation report will be due after the gas well has been plugged and abandoned.” That may be a while. Last year the well produced 25,500,000 cubic feet of natural gas, worth roughly $56,000.

When a previous company wanted to put a well atop the untouched mesa behind Richard’s home, he offered a spot at the base of the mesa, 500 feet from his front door. “I’d rather have that than destroy this last piece of land we got,” he said. There are now 30 active gas wells within a mile of Richard’s house.

The family coped with all of it over the years with different companies.

“We did have a good working relationship to them,” Kaleb said.

And the Hodgsons do a lot of work in their three main businesses on the ranch: raising cattle, hosting elk hunts and maintaining the maze of dirt roads connecting all the wells on the property. That maintenance happens — happened — through a long-running series of agreements with oil companies going back years.

Richard and Kaleb said that earlier this year, a new landman — the person companies hire to deal with landowners — began slowly cutting them off. They don’t know why. The landman didn’t take their calls. He said if the Hodgsons had anything to say, they could call Hilcorp’s lawyers.

The Hodgsons said Hilcorp also canceled its agreement with them to maintain the roads on the property. In addition to clearing access to the wells, that work channeled the region’s intermittent — and occasionally torrential — rains off the roads and well pads and onto surrounding grasslands. The work was good for the oil crews, good for the Hodgsons and good for the livestock and wild game. Plus, there was no way the Hodgsons could afford to do the work without the contract.

“They come up fighting like I’ve never seen an oil company do after 40 years,” Richard said. “I’ve never had a company just stomp their feet … and say, ‘We ain’t going to deal with you.’”

In September, after months of deteriorating relations with Hilcorp, a line was crossed.

The Hodgsons nurture the elk population on their land. “We take care of them all year round,” Richard said. “We provide feed, shelter and water. And then we do harvest some.” Hunters pay thousands of dollars for that privilege. But it’s not easy to track wild animals over thousands of acres, and successful hunts aren’t guaranteed. Many factors can spoil a hunt.

To keep some variables in their favor, every year Richard and Kaleb have negotiated with Hilcorp and its predecessor companies to keep trucks off certain roads in the early mornings and early evenings. That allows elk to gather in herds to eat and drink, increasing the chance that hunters can find them amid the mesas. Kaleb said he texted the landman the day before a scheduled bow hunt, asking Hilcorp to keep trucks away from specific areas, and the landman agreed.

It was 6 a.m. the next day, just before dawn. One of Kaleb’s nephews was walking slowly between pine and cedar trees in the faint light atop a mesa, leading a small group of bow hunters. They had spent the night in a camp to be ready at first light. At that point, they could see elk gathering in the valley below.

Then they heard a truck, and the elk scattered.

The nephew texted Kaleb to explain what happened, but the damage was done. The hunters hiked to the next valley over, hoping to find more elk, but didn’t.

“We’ve had these hunters for five years,” Richard said. “They’ve always paid a deposit for next year, and [this time] they didn’t pay no deposits. I don’t think they’re coming back.”

The spoiled hunt was a clarion call for the family. “It showed us that they put a bullseye on us,” Richard said.

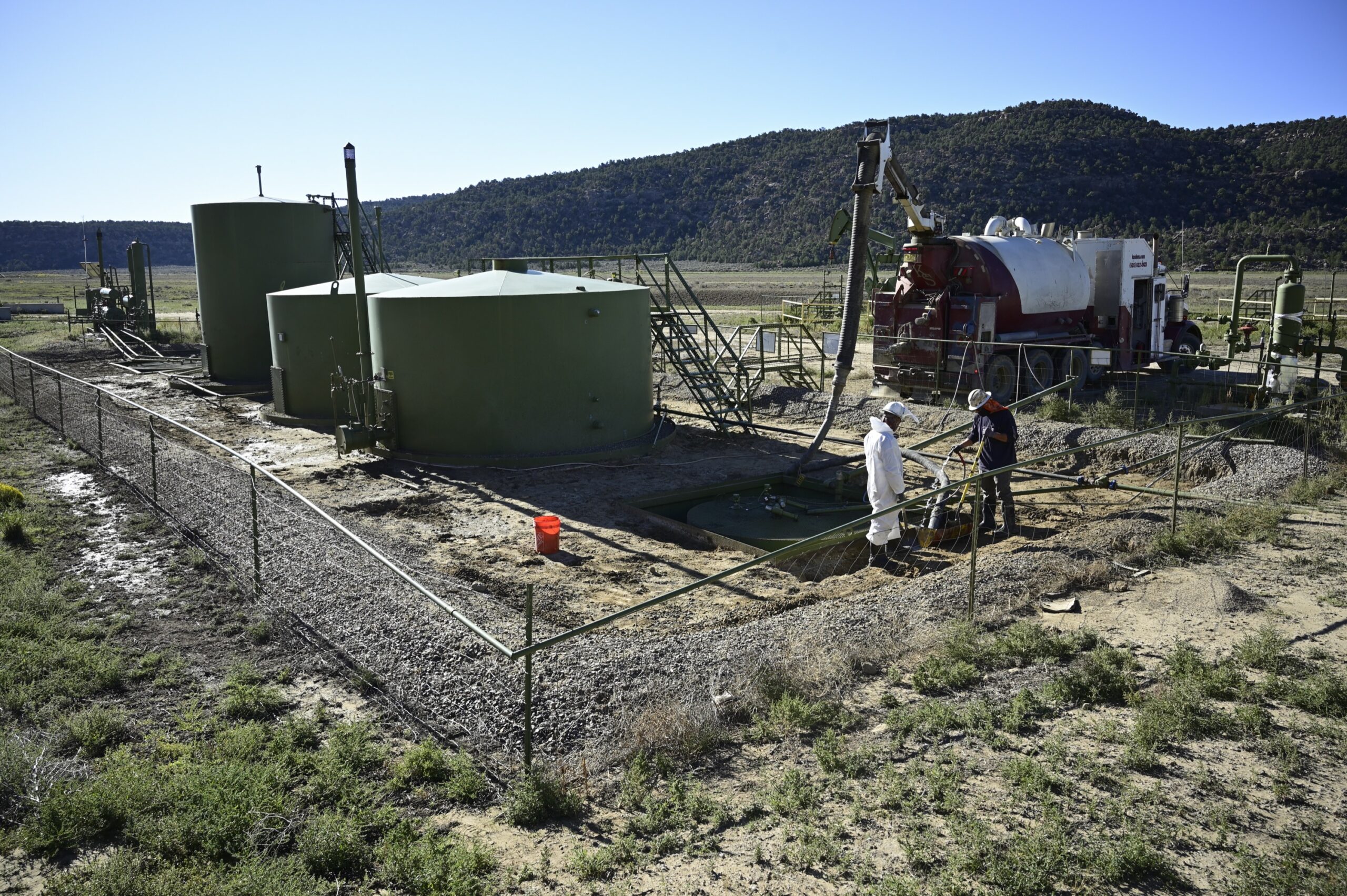

Meanwhile, other problems grew. A week and a half after the botched hunt, water from a colossal cloudburst ran off the mesa behind their houses, washed over one of the untended roads and flooded a well pad with two and a half feet of water. The water flushed the sludge from two open-top below-ground storage tanks, creating a pond of black goo. Kaleb kept a mason jar filled with a sample, which had the consistency of old motor oil.

Several days later, while standing next to the muddy well pad, Kaleb explained how much waste Hilcorp told him was flushed from the tanks. “They say it was only 21 barrels, but it covered that whole entire berm,” he said. At two and a half feet deep, the 5,400-square-foot area inside the berm could hold roughly 2,400 barrels of liquid.

Kaleb said that much of the oil and water simply sank into the ground. As he spoke, workers from a cleanup company shoveled contaminated soil into a vacuum truck that could hold 80 barrels, the second that Kaleb had seen at the site.

“Contaminated dirt should have been dug out,” he said.

Kaleb said he sees the resulting problem as twofold. There’s the obvious groundwater contamination from the spilled sludge, and then there’s the wasted rain water. If the roads had been maintained, the runoff would have bypassed the well pad and filled a pasture the Hodgsons have nurtured over the years, turning two hundred acres of scrubby dirt to a grassland that feeds cattle and other animals.

“We wasted all that water,” Kaleb said. And the waste may have polluted the land where the family’s cattle and elk graze.

Though Hilcorp didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story, after Capital & Main visited the ranch, the Hodgsons said company representatives asked them if they had been talking with journalists. “I think we somewhat got their attention,” Richard said.

He said Hilcorp sent a new landman, who allowed the Hodgsons to fix the washed-out road near the flooded well pad so it wouldn’t flood again. Hilcorp also tested the soil there. “They did some core drilling, but I won’t accept that,” Richard said. “We’ll have to dig it out and find out what we got.”

He said Hilcorp also hired a company to take care of another spill he recently came across. After months of problems, Richard and Kaleb are skeptical of the quick about-face.

“They’re getting really worried about these spills because they know that I’m upset, and I’m going to make some noise,” Richard said.

“I’m not saying, ‘Do not drill.’ I’m just saying, ‘Do it reasonably,’” he added. “I mean, hell, the country’s making you just very, very wealthy. Why would you not put a little bit back into what you tear up?” he asked. “That’s all I want these companies to do. Just be reasonable.”

After the Hilcorp truck spoiled the elk hunt, Richard and Kaleb got in touch with their nearest neighbors, Don and Jane Schreiber, who live about 15 miles away. “There are not very many of us that live out here,” Richard said. “So anybody who can live out here and appreciate the land is a friend of mine.”

The Schreibers are known for fighting oil and gas companies that thoughtlessly drill or poorly maintain wells on their land. And like Richard, Don grew up in Farmington and harbored a dream of running a ranch. Also, like the Hodgsons, the Schreibers’ own land is split-estate.

The Schreibers bought their ranch in 1999 and over the years they have slowly sold off their cattle and leased the land to other ranchers. “I turned my back on my dream,” Don said. Instead, they spend much of their time raising awareness about how oil and gas drilling has degraded the landscape in the northwest corner of the state.

“We had two blissful years out here,” Don said of their earliest ranching days. “But then the fights started.”

He said a childhood friend who worked for an oil company explained to him what companies thought of the Schreibers’ ranch and lands like it: “Pard, I don’t want to hurt your feelings, but we’d just as soon have this S.O.B. paved.”

After a half-dozen years of contesting sporadic oil and gas well proposals on their land — which they lost — the Schreibers’ big fights with oil and gas companies began in earnest in late 2007, when a company proposed drilling 44 new wells on their property. The Schreibers thought most of those should be “twinned,” by adding the new wells to existing well sites, which would preserve untouched ranch land from more well pads and connecting roads. After an “intense fight,” the company put in just 22 new wells, all “twinned” on existing pads, Don said.

“So in the end, we did win,” he said. But, he added, “I mean, every time you drill a well, you lose a bit.”

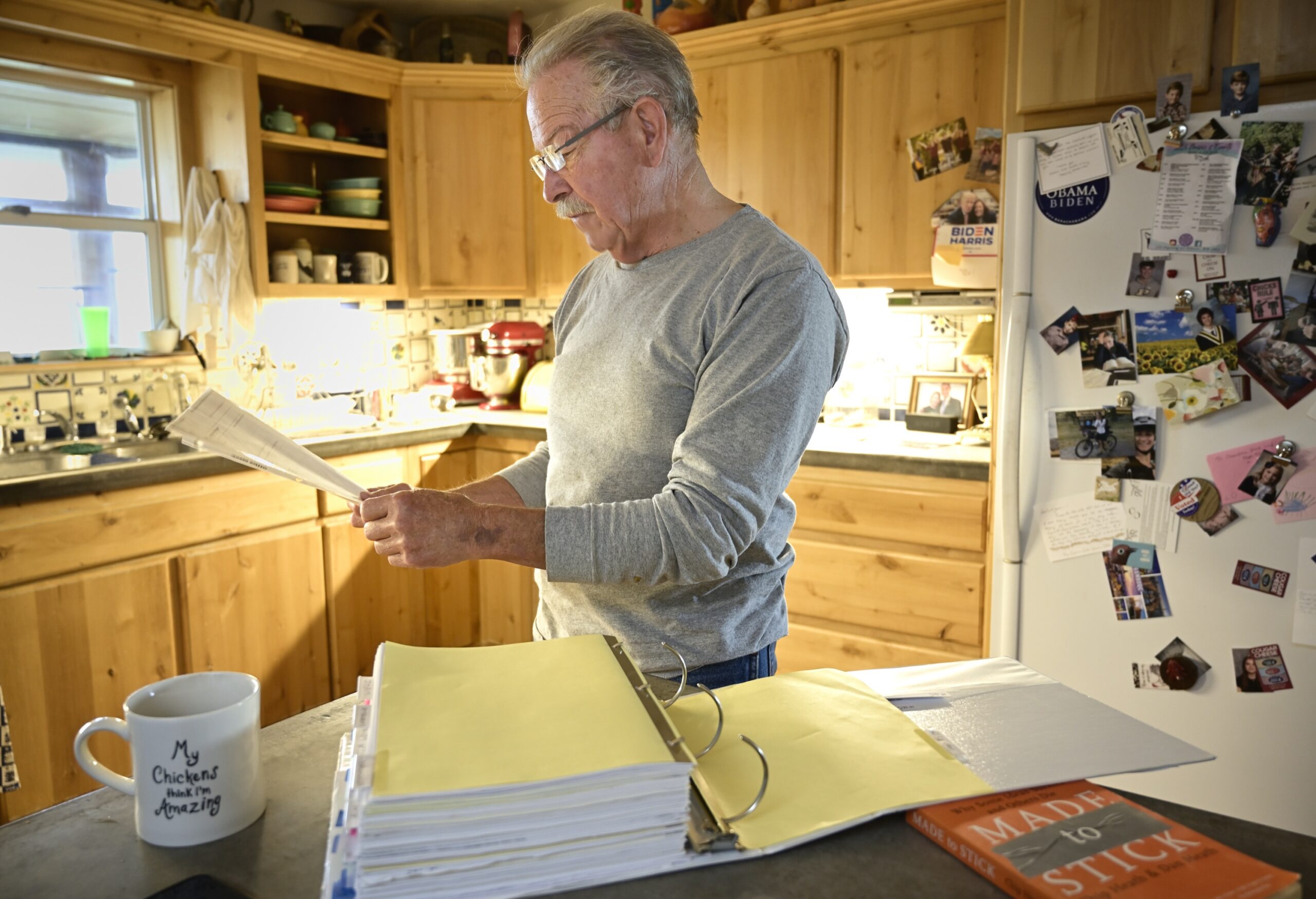

Over the years, Don and Jane recorded each tussle, filling binders with letters, emails and documents recording the slow but relentless fights to protect their land. Don also keeps a small display with photos of nine separate incidents in which he got a company to clean up an unacknowledged mess or unnecessary well. He shows it off at public meetings and to company representatives at their first meetings. He said its message for them is clear: “I don’t know if it’s gonna take four years or 14 years — we’re gonna beat you.” In his experience, constant, determined pressure gets a company to do what you want it to do.

It’s a style of work familiar to the Hodgsons.

In late September on an afternoon spent driving to a far corner of the ranch, a thin column of diesel smoke from a distant fracking site was the only thing that marred a crisply blue sky. The San Juan Mountains in southern Colorado sketched a dark jagged blue line on the horizon. Richard, his grandson Luke Whitley and Kaleb were out to round up some cows that had wandered off a pasture.

Aside from their Ford dually pickup and cellphones peeking from their pockets, the three could have walked off a Western film set a century ago. Each wore a cowboy hat — Kaleb’s in black felt — as well as scuffed boots with worn spurs. Later, they donned scarred chaps to protect their pants from the sage, juniper and piñon trees. Three calm horses and a clutch of excitable ranch dogs rode in the trailer behind. The leather on the horses’ saddles was dull on the sides and polished in the seats from years of use.

As he drove, Kaleb described how he and his family trained horses — an integral part of running the ranch.

“Horses are very smart, complicated animals. But also they’re very simple,” he said. “They react off of your pressure.” Pressure from the reins, pressure through the knees. Pressure and release. Slowly pressure the horse in the direction you want it to go — then release the pressure.

“You do that a few times. And then you ask for half an inch. And then you do that a few times and you work your way up to an inch. Then you’re asking at the end of it for a foot,” he said.

Kaleb said all horses react to pressure and release in some way. “Even bucking horses,” he said. “They’ll react to pressure and release if you’re just consistent with it.”

Eventually, no matter how big or powerful the horse, careful, determined pressure gets it to do what you want it to do.

The same principle appears to be working in their relationship with Hilcorp.

After meeting with the Schreibers and calling Capital & Main, the Hodgsons said Hilcorp honored their recent late-September elk hunt hours and have been working on the spill sites. But Kaleb and Richard remain ready to apply more pressure.

“I don’t know where we’re going to go with all of it,” Richard said. “[We’re] just not letting anything lie.”