Data revealing tens of thousands of lung-penetrating microplastics are suspended in the air we breathe underscores a critical need for further research, an Australian plastics expert says.

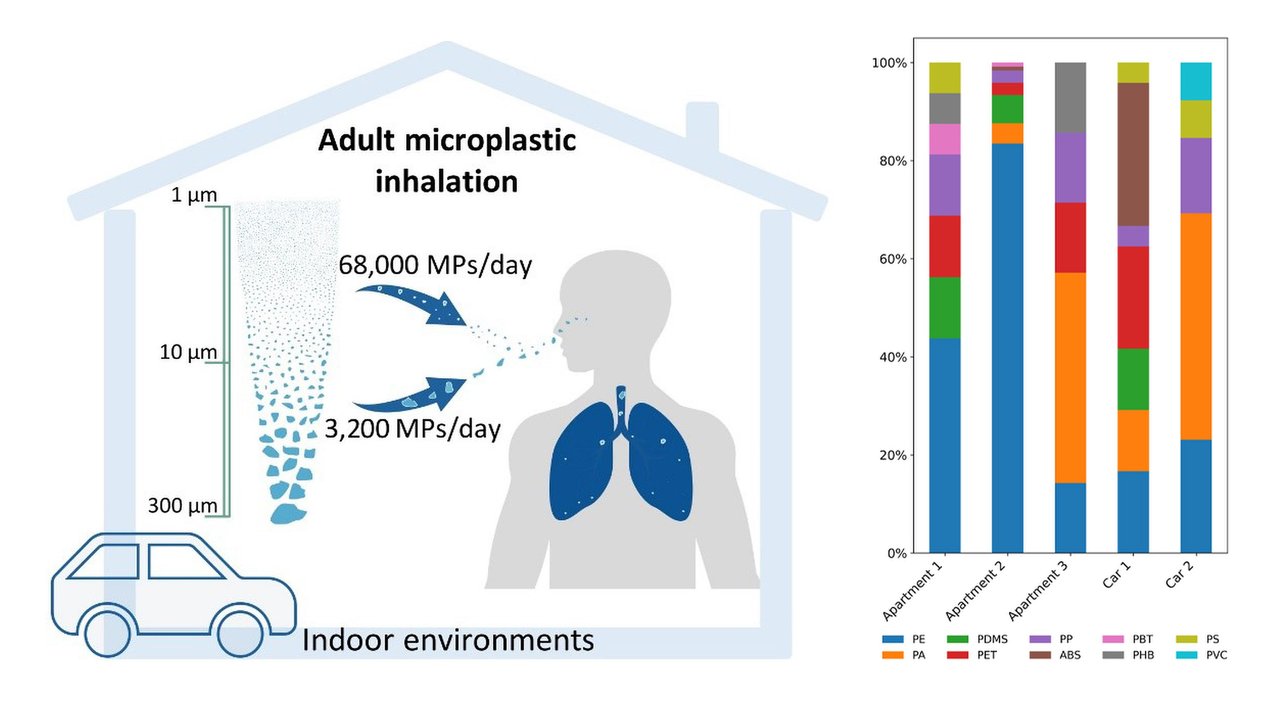

A French study published on Thursday AEST found about 68,000 microparticles floating in apartments and cars.

Most of the particles were smaller than a speck of dust, and seven times thinner than the width of a strand of hair, the French researchers leading the study said.

Their small size means the microplastics are tiny enough to be inhaled deep into the lungs, increasing the risk of immune-system effects and organ damage.

The study published in PLOS One shed new light on understanding the risks of microplastic inhalation, as prior research had focused on larger particles that were unable to penetrate the lungs, the authors said.

Researchers collected air samples from their apartments and cars, and combined the results with previously published data on exposure to indoor microplastics.

They found indoor air was a previously underestimated place of exposure to microplastics, with car cabins detecting concentrations 100 times higher than previous estimates.

Once they were deep inside the lungs, microplastics released toxic additives that reached our blood and could cause multiple diseases, the authors said.

The findings from postdoctoral researcher Nadiia Yakovenko and her colleagues at the Universite de Toulouse in France were published online on Thursday.

Professor Thava Palanisami from the Australian Plastic Research and Innovation Lab, who was not involved in the research, said the findings revealed exposure levels much higher than previously estimated.

"(They) underscore the need for a critical reassessment of airborne microplastic exposure pathways, and their potential for deep lung penetration, systemic translocation, and associated toxicological impacts," the University of Newcastle professor said.

Professor Ian Rae from the University of Melbourne said the study's experimental work was well done, but the results showed a scatter of plastic types that made interpretation of the results difficult.

Coloured bar graphs in the paper showed significant differences between the microplastics collected in apartments, and those collected in cars, he said.

There were also disparities between the separate apartments and vehicles.

"It's hard to know why these interior atmospheres are so different," Prof Rae said.

He pointed to the material makeup of the cars and apartments, as well as their occupants' behaviour, as possible explanations for the variation in data.

20250731153079280170