Inside the Taxpayers’ Union’s in-your-face push for change. Part 1 of a 2 part series.

Imagine if an organisation that raised millions of dollars from unknown donors and employed almost as many people as the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment tried to influence the election.

Not only that, but its campaign was waged, in the main, in public view, and within the rules.

READ MORE: * Chiding in plain sight, Part II * Your pre-COP climate denial inoculation * Cindy Baxter: Who the hell is Gideon Rozner, anyway?

As the dust settles on a bitter election campaign, questions are being asked about the influence of corporate and private money in our politics. Some of those questions will no doubt be directed at the free-market think tank the Taxpayers’ Union (TPU).

Between August 1 and election day, it paid for polling at the national and electorate level, issued almost 100 press releases, hosted seven political debates, published four policy reports, started a petition, and drafted alternative legislation.

A debt clock gimmick was rolled out. Taxpayers’ Union staff appeared in the media as commentators.

One way or another, many, if not most, citizens would have tripped over the Taxpayers’ Union's work, and its constant messages about taxes being too high, the government over-spending, and wasteful bureaucracy.

Its critiques were mostly aimed at the sitting Labour government. And though it did occasionally praise National, it also criticised the party for not going further.

After the election, in which the country lurched to the political right, Newsroom asked the Taxpayers’ Union if it influenced the election. Executive director Jordan Williams responded: “We certainly hope so!”

On election night, Williams and Taxpayers’ Union co-founder David Farrar, the National Party pollster, attended the National Party event.

Nobody spoken to by Newsroom alleged the Taxpayers’ Union had broken any rules.

It registered with the Electoral Commission as a “third-party promoter”, which means it has limits on advertising spending, and has to adhere to rules on advertising disclosures and signs.

There’s no suggestion it won’t comply.

However, the commission’s manager of legal and policy Kristina Temel confirms third-parties don’t need to disclose their funding sources.

Also, much of the Taxpayers’ Union’s activities fall outside the Electoral Commission’s oversight, which is restricted to advertising.

As a free-market think tank, the Taxpayers’ Union’s principles are clear, and it has declared its association with the global Atlas Network umbrella group.

But is it acceptable for the funding of such an influential group to be a black box? And what about its direct influence on politicians and policy?

Timothy Kuhner, an associate professor of law at the University of Auckland, says the lack of transparency from third-party promoters is problematic.

“What we’re seeing is an increase in the number of ways that people can influence electoral outcomes, and the formation of public opinion, free from public scrutiny.”

The public’s probably familiar with the concepts of hard and soft power: the former using a stick or a gun to gain influence; and the latter attempting to persuade people with values or investment.

Kuhner says there’s another type called conditioned power, in which groups construct issues in a way that’s favourable to their interests.

Your average voter might not be thinking deeply, or in a Machiavellian way, about how topics like climate change, taxation, and immigration are portrayed during an election campaign.

Speaking of what’s happened recently in the United States, Kuhner says: “That prioritisation of issues is something that’s been paid for and constructed and strategically built. And so I really worry about that.”

In theory, political parties are supposed to channel public opinion and people’s interests to form ideas of public good and political will.

“And then you get these registered promoters who can start to outspend political parties or outmanoeuvre political parties, and what they’re trying to do is kind of construct a very different type of political will – which is a political will tailored to, generally, the economic interests of their supporters. Sometimes it’s the ideological interests of their supporters.

“But either way, it’s unaccountable, and it’s opaque. The label I would put on all this stuff is privatisation of democracy.”

What we know about TPU, and what we don’t know

The Taxpayers’ Union’s formation was announced 10 years ago on October 30, 2013.

John Bishop, the father of National Party MP and campaign strategist Chris Bishop, was founding chairman, and Farrar was a board member.

Williams, a lawyer, was named executive director. He was enmeshed at different times with Act party politics – working as an intern for leader Don Brash, and for MP Stephen Franks’ 2008 election campaign. He also worked at the latter’s law firm.

In Nicky Hager’s 2014 book, Dirty Politics, Williams was described as one of Whale Oil blogger Cameron Slater’s closest political associates, and the “apprentice” of National’s strategy consultant Simon Lusk.

In 2011, Williams fronted an anti-MMP campaign group, Vote for Change, whose campaign manager was Lusk, and Slater did “a large part of the work”, wrote Hager, through Whale Oil posts.

Hager detailed how Williams was involved in rolling Act leader Rodney Hide in 2011, by talking to a woman Hide had been sending “dodgy texts”.

(Hide told Stuff the allegation was untrue, and Williams called it “utterly, utterly false”. In the same story, he said he’d fallen out with Lusk, and, though he talked to Slater every day, denied the Taxpayers’ Union worked in concert with Whale Oil.)

Williams was involved in another political leader’s downfall, that of Conservative Party’s Colin Craig.

A long-running court feud ended, in 2019, with Williams paying compensation and issuing an apology.

Williams is also a founding council member of the Free Speech Union, which became an “intervener” in the High Court’s consideration of whether anti-trans activist Kellie-Jay Keen-Minshull, or Posie Parker, should be allowed entry to New Zealand.

Though the Taxpayers’ Union’s accounts are public, its funding sources are not. Its financial statements from last year, made public last month on the Incorporated Societies website, show its income was $2.8 million, $2.6 million of which was from donations. Not bad for an outfit with income of $355,000 in 2017.

In the Taxpayers’ Union’s first press statement, in 2013, its founders described it as “a politically independent grassroots campaign to lower the tax burden on New Zealanders and reduce wasteful government spending”.

The independence claim has been repeatedly knocked.

In Dirty Politics, Hager wrote the Taxpayers’ Union “operates, in effect, as an arm’s-length ally of the National Party” and called it a “political tool”.

The following year, political scientist Bryce Edwards described the Taxpayers’ Union to the NZ Herald as “the Act Party in drag”.

Its modus operandi for revealing wasteful spending is to flood councils and government departments with official information requests. But that hasn’t always gone smoothly.

The NZ Herald wrote in 2018 how it had been caught making requests using fake identities.

After proudly stating it would never take Government funding, Taxpayers’ Union applied for and received more than $60,000 from the wage subsidy scheme during the Covid-19 lockdown. A search for its name on the Work and Income website this week drew a blank, suggesting it paid the money back.

In November 2021, the Taxpayers’ Union was unmasked as the company that registered the www.motherofallprotests.nz domain name, showing its direct link to fringe agricultural group Groundswell. (That was changed, soon after, to Williams’ digital marketing firm The Campaign Company.)

That same year, ex-Act staffer Grant McLachlan said Act weaponised so-called astro-turfs – groups that masquerade as concerned citizens but actually push the interests of large corporates.

McLachlan told RNZ the Taxpayers’ Union “did a lot of the groundwork” for the Act Party in the 2020 election campaign through its Campaign for Affordable Housing. “It was actually a contrived problem that the Act Party told them to create.”

In response, Williams said it was ridiculous to suggest the Taxpayers’ Union was a mouthpiece for any political party. He has repeatedly mentioned its wide membership and that the majority of its money comes from “small dollar donations”.

A Guardian investigation in 2019 revealed the Taxpayers’ Union, which had railed against cigarette tax increases and plain packaging laws, received money from British American Tobacco.

It’s better about disclosing interests these days.

In an August 22 press statement headlined “Vaping crackdown will jeopardise Smokefree 2025 goal", the Taxpayers’ Union made this disclaimer: “2.1% of the Taxpayers' Union annual income is from membership dues and donations from private industry, which includes contributions from the nicotine, alcohol, sugar, and construction industries.”

Newsroom asks Williams about the Taxpayers’ Union’s funding, staffing, and influence.

He confirms it has 18 staff on its payroll, and used a couple of contractors during the election campaign. That’s roughly equivalent to the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment which, according to its latest annual report, employs 20 staff.

Though the Taxpayers’ Union’s accounts are public, its funding sources are not.

Its financial statements from last year, made public last month on the Incorporated Societies website, show its income was $2.8 million, $2.6 million of which was from donations.

Not bad for an outfit with income of $355,000 in 2017.

“Our income will not be significantly different to last year,” Williams says.

He admits to some international funding.

“I’m not aware of any funding from individuals overseas who aren’t either expat Kiwis or own houses and spend their time in New Zealand.”

As president and chair of World Taxpayers Associations (an Atlas Network partner), he gets some travel expenses paid.

The Taxpayers’ Union has also won awards and travel scholarships from the Atlas Network, chaired by New Zealander Debbi Gibbs, daughter of the businessman Alan Gibbs, a long-time supporter of the Act party.

“We publicly disclose these,” Williams says of the Atlas money. “For example, our investigations co-ordinator recently won the Asia ‘Shark Tank Competition’ – successfully pitching a campaign idea in a Dragons’ Den-style event during the Asia Liberty Forum in Malaysia.”

The $US10,000 prize winner was Oliver Bryan, a former political advisor for a British Conservative Party politician.

“The prize money, and other Atlas funding, is small in terms of our overall budget. It has never constituted more than 1 or 2 percent of our annual income, and it is our only funding from overseas.” (This last statement jars with the earlier one about individual donations.)

Back home, some listed companies and well-known brands donate to Taxpayers’ Union, Williams says, but its industry income is low by international standards – at the aforementioned rate of 2.1 percent.

The bulk of its donations average $65. “It was mostly raised through small dollar / online giving from tens of thousands of New Zealanders among our hundreds of thousands of subscribed supporters.”

Some of those supporters are MPs, with Williams confirming a dozen or so are members.

“None, as far as I know, have given more than $50 or $100. The joining fee is $25, and most will have just paid that.”

(Williams says various former staff work “in and around the NZ First, Act, and National campaigns”, and former Taxpayers’ Union chair Casey Costello, who resigned as a board member to stand for NZ First, will enter Parliament on the party’s list. The mother of a Taxpayers’ Union researcher was a Labour MP until last weekend.

There is a funding anomaly.

According to year-old data on its website, 17.4 percent – as much as $487,000 – of Taxpayers’ Union funding comes from the so-called Taxpayers' Caucus.

Policy positions can’t be influenced by donations, its website states. It also respects the privacy of supporters – which translates as donating without fear of being outed.

The Taxpayers’ Union’s membership and one-off donations have soared over the past two years as it tapped into opposition to major government policies, such as Three Waters and Co-Governance.

“The Taxpayers’ Union ran the ‘Stop Three Waters’ campaign and, more recently, the ‘Hands Off Our Homes, Stop Central Planning Committees’ campaign," says Williams. "With the exception of the ‘Stop Three Waters’ campaign, the vast majority of our creative and digital work was in-house.”

Its association with Groundswell – the Taxpayers’ Union registered the motherofallprotests.nz website in 2021, before the name changed to Williams’ digital marketing agency, The Campaign Company – has no doubt pulled in a new source of support: disaffected rural people.

(Williams argues the Taxpayers’ Union led a public change in attitude on Three Waters. “By the time we had an alternative, broadly supported by our supporters, and the group of councils who shared our concerns, it was pretty easy for the centre-right parties to adopt the same, or consistent, policies.”)

The Campaign Company helps various political and commercial clients in New Zealand and overseas, Williams says.

“I don’t manage it day-to-day, and nor could I disclose client matters without their permission.”

(However, it’s known the Campaign Company worked, briefly, on failed Auckland mayoral candidate Leo Molloy’s election campaign, while, confusingly, another Taxpayers’ Union offshoot, the Auckland Ratepayers’ Alliance, criticised Molloy.)

Did the Taxpayers’ Union’s almost 100 press statements and its polling during the election campaign get it more media mentions than ever before?

“We did OK through the election, but we certainly didn’t get as much media as we used to get during the [National Party leader and former Prime Minister John] Key administration,” Williams says.

“TV, in particular, appears to have become a lot less balanced – for example, the CTU’s critiques of National’s alternative budget numbers were run largely unchallenged, while the quite obvious holes and flawed assumptions in Labour’s GST policy costings didn’t even make TV.”

(It did make the NZ Herald, however – which ran criticism of Labour’s GST policy from the Taxpayers’ Union.)

In the think tank world, Williams says it’s difficult to measure policy impact.

“If you are successful, and you manage to make good policy popular, the politicians take the credit for what by then is ‘common sense’.”

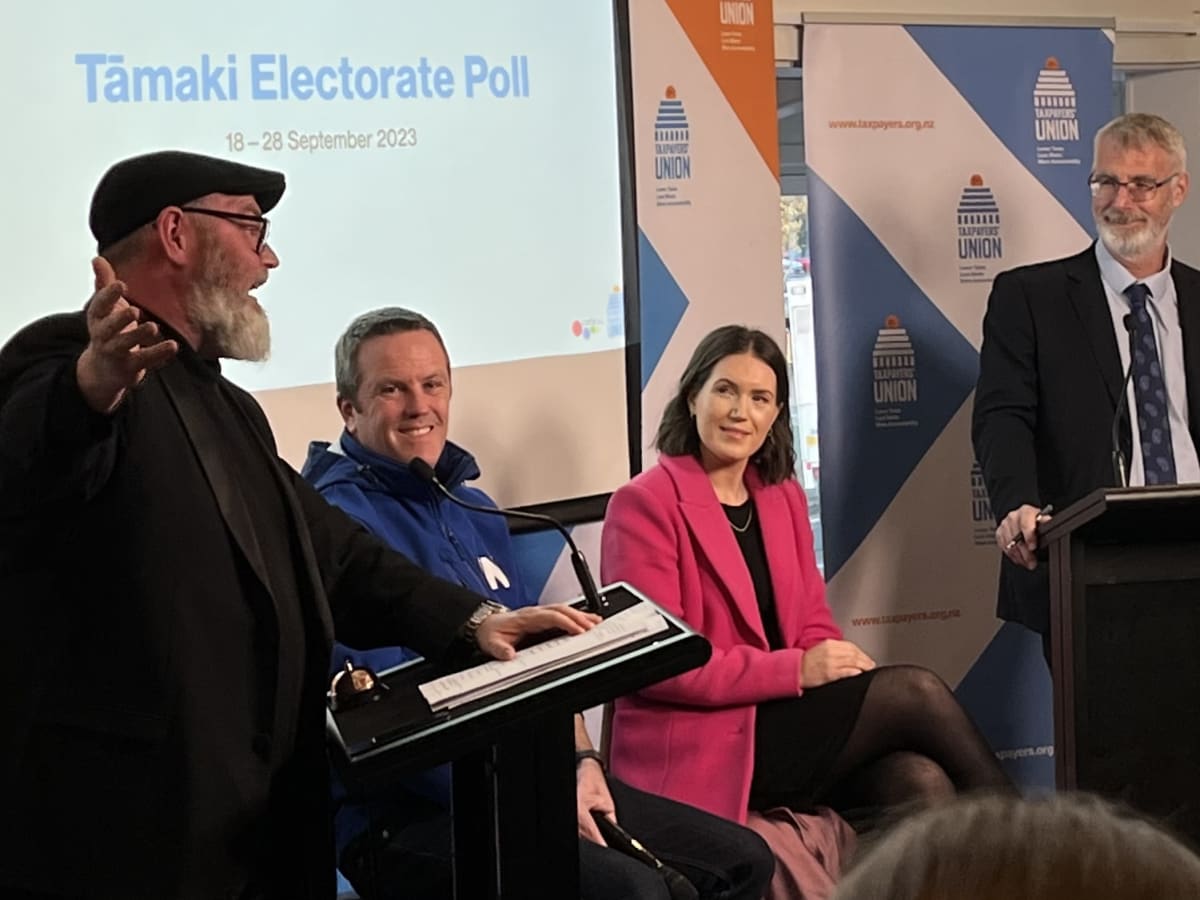

One way to create influence is through polls – something the Taxpayers’ Union did at a national and electorate level during the election campaign.

“We see organisations all over the world funding and putting out polls, and poll questions, in order to enhance things like press releases, in order to enhance campaigns, and in order to create a sense of consensus,” says Dr Lara Greaves, an associate professor in political science at Victoria University of Wellington.

If there’s public consensus on an issue, and you repeat it enough, that creates the “social reality”, Greaves says. But it’s important to check the wording of poll questions to check for agreement bias – because people being surveyed tend to agree with statements.

Something else people like to do is follow the leader – known as the bandwagon effect.

“We’ve seen a lot of arguments on things like a wealth tax, for example,” Greaves says. “People will repeat poll results, or repeat this and that, and it creates that consensus.”

An example in this latest election was Labour’s line it was getting a last-minute surge in the polls, in an attempt to create a consensus it was going to do well.

Polls play an important part in democracy, Greaves says, to help get a finger on the nation’s political pulse.

Greaves says if an electorate poll shows a candidate’s not going to win people might be less inclined to vote for them. “People also don’t understand the limitations of electorate-level polls.”

Political commentator Grant Duncan, a freelance writer and scholar, says polls make a difference but there are many different ways in which people are influencing one another.

“I think the question is, what do we regard to be as a fair and democratic level of influence, that where vested interests aren’t using their economic clout, you know, in their finances, in their networks, and so forth, in ways that are injurious to the public good?”

Taxpayers’ Union headlines on poll-related press statements:

Labour crashes and Winston's back

National leads in Napier electorate

National lead in Ilam Electorate

National/Act could form government comfortably

National Lead in Northland Electorate

Voters torn in Auckland Central electorate

Statistical tie between National and Act in race for Tāmaki

Kiwis don’t believe Winston when he says he would not work with the Labour Party again

Cost of Living Bites Taxpayers as They Head to the Polls

Kiwis overwhelmingly support inflation-adjustment of income tax brackets

Kiwis oppose Government’s plans to strip planning powers from councils

Party political finance is a skewed playing field, Duncan says. The wealthy have more money to donate, and they’ll donate to parties that are going to represent their interests.

But third-party activities are more even. He mentions the Council of Trade Unions, which had “a very well-organised and financed attack campaign” on National leader and Prime Minister-Elect Christopher Luxon during the election.

“But we don’t necessarily know where that money is coming from – and that’s the thing that troubles me.”

We asked the same questions of the Council of Trade Unions that we asked the Taxpayers’ Union.

Secretary Melissa Ansell-Bridges says the campaign was financed by the Council of Trade Unions, affiliated unions and donations from the public, and overseen, in the main, by one staff member – although others contributed as required.

“The amount spent will be reported in due course, but pales beside the large contributions made by businesses and wealthy New Zealanders to National, and Act.”

Its objective was to highlight the costs to many communities from National and Act’s policies – including the axing of Fair Pay Agreements, the unfairness of tax cuts, and the risks to public services.

Ansell-Bridges says the Council of Trade Unions contributed to the debate on these policies and highlighted “fundamental flaws” in National’s tax plan, “such as how few families would receive the maximum tax cut benefit”.

“We wanted the retention of a centre-left government which has the interests of working people at its heart, and so we are disappointed this has not happened and share the worries of many from the policies that may now be enacted.”