Several years ago, while visiting the Roman Baths in Bath, I found myself overwhelmed by a profound feeling of existential insignificance. Standing beside the spring water in the remarkably well-preserved bath house, I started picturing the humans, not so unlike me, who had come to wash themselves at that exact spot almost 2,000 years earlier. Each of them doubtless had hopes, dreams and everyday worries that seemed vitally important, yet all of them had long since been rendered flatly meaningless by the same indifferent march of time that would one day relieve me of my own trivial ambitions. It was almost enough to put me off my souvenir fudge.

That same disorientating sensation rushed back to me as I watched How to Shoot a Ghost, a short film by Charlie Kaufman that screened last Friday at AFI Fest in Los Angeles. Kaufman has often explored the big questions of life, death and memory in surreal and astonishing screenplays, including Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Synecdoche, New York, but here he directs from a lyrical script written by the Canadian-Greek poet Eva HD.

The new short follows a translator (Josef Akiki) and a photographer (Jessie Buckley) who have both recently died of unrelated causes in Athens, a place already teeming with the ghosts of various eras. As the spectral pair wander through the ancient city snapping pictures, Kaufman cuts their narrative together with street photography, historical footage and old home videos. The wistful film invites us to wrestle with our own doomed attempts to preserve or capture our fleeting, ephemeral existences. “[Buckley’s] character is trying to hold on to life,” Kaufman tells me the morning after the screening. “I think that’s her motivation in photographing everything, and she can’t. No one can, but certainly after you’re dead you can’t.”

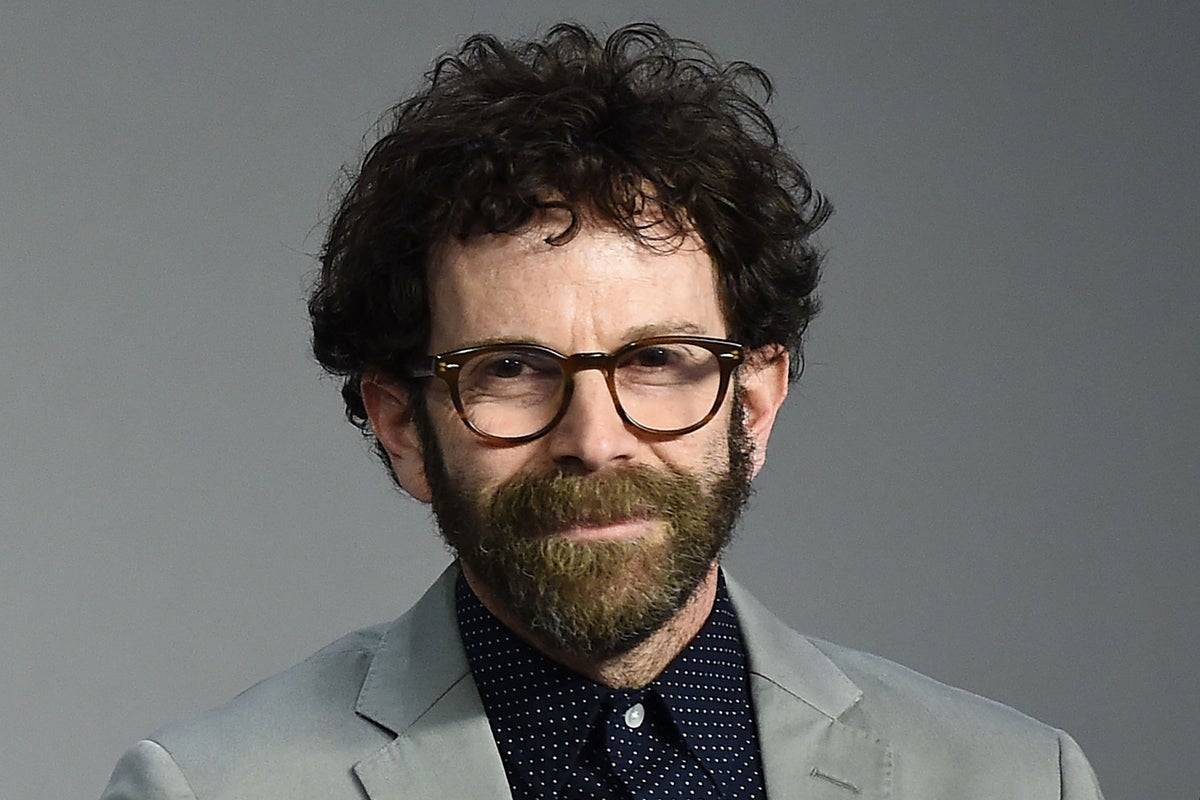

He’s sitting in a light-filled LA hotel room, bearded and bespectacled in a loose blue T-shirt, beside the denim-clad HD. With their matching dark curls and knack for making each other laugh, the collaborators could almost pass for siblings. They’ve been friends since meeting at New Hampshire’s MacDowell artist residency in 2017, when Kaufman was working on his acerbic and labyrinthine debut novel Antkind. They bonded over always being first down for breakfast. “One of us being an insomniac, and one of us being an early riser,” explains HD, before Kaufman cuts in: “We won’t tell you which is which, but you can speculate.” (My money’s on HD being the morning person.)

Their working relationship began when Kaufman was directing the 2020 psychological thriller I’m Thinking of Ending Things and needed a morbid poem for the film’s protagonist, also played by Buckley, to recite. He settled on HD’s “Bonedog”. Three years later, the pair reunited to make their first dreamlike short, Jackals and Fireflies, set in New York and based on another of HD’s poems. She wrote How to Shoot a Ghost specifically because she wanted to make a follow-up in Athens.

It’s the sadness of the walk of shame ... There is something very sad that we all know about a girl in her party clothes in the bright light of day

After I tell them both about my existential crisis in Bath, HD explains that in Greece, she too gets a sense of time collapsing on itself. “When you’re somewhere where people in history were not doing historical things, they were just falling in love or having a bad day or washing their clothes or their bodies, you transcend the veil a little bit,” she says. “You realize where you are situated in this continuum and how tiny that is.”

Kaufman picks up the thread. “The continuum is not only that there are these people who lived all these years ago and they’re all gone,” he begins. “You reminded me that I was in Bath 40 years ago, and that person is me, but not me. That person doesn’t exist anymore, even though I’m an iteration of them. My experiences there as a tourist without any money were very mundane, but it touched me somehow to hear you say that.”

For Kaufman, his obsession with mortality started young. He grew up on Long Island in the 1960s and remembers asking his mother one night while she was putting him to bed whether he was going to die. “She said: ‘Yes, but not for a very long time,’ which was actually kind of helpful for me at that time in my life,” he recalls. HD suggests that his mother’s comment was arguably “a wish and a bit of a lie… she’s not going to tell you: ‘Yes, you might die tomorrow.’ That’s probably her greatest fear. She needs to insulate herself against it.” Kaufman nods, repeating that his mother’s words meant a lot to him. “It felt kind to me,” he says. “It was a good thing that my mother did.”

After starting his career as a writer for largely forgotten television comedies, such as the Chris Elliot sitcom Get a Life and a short-lived sketch series called The Edge, Kaufman wrote the mind-bending screenplay for Being John Malkovich in the hope it would catapult him into a career in film. “I would get these meetings, because it became ‘a thing’ that people loved in Hollywood,” he remembers. “They would say: ‘It’s the funniest thing I’ve ever read, no one will ever make it.’ I was told that at least 10 times by different people, which seemed odd to me at the time. Like, if this is the funniest thing you’ve ever read, shouldn’t you try to get it made into a movie?”

His fortunes changed when the script found its way to Spike Jonze, then an acclaimed music video director who decided to make it his debut feature in 1999. “He had clout in the industry, so he was able to get the financing,” explains Kaufman. The pair reunited for 2002’s Adaptation, starring Nicolas Cage in a meta dual role as Kaufman himself and his fictional brother Donald as they struggle to adapt Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief.

Kaufman says he’s sadly resigned to the fact that no studio would ever take a chance on a similarly inventive script today. “There was a mid-range film business in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and it doesn’t exist anymore,” he points out. “After the financial crisis in 2008, the business changed and franchises became the dominant form. I can’t get features made and it’s been that way since 2008, with a couple of exceptions.”

.jpg?trim=0%2C153%2C0%2C42)

It should go without saying that Kaufman's inability to get features made is a damning indictment of a film industry in decline. There was a time when he was fêted by Hollywood, winning the Best Original Screenplay for 2004’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. The wholly original romance — about a couple drawn back to each other even after erasing their memories — remains deeply beloved. Somewhat surprisingly, HD confesses she’s never seen it.

Any parallels between Eternal Sunshine and the efforts of the characters in How to Shoot a Ghost to cling on to their fading memories are therefore seemingly coincidental. So too is Buckley’s blue wig, which seems to invoke a dye job in a similar shade worn by Kate Winslet’s Clementine in Eternal Sunshine. “That was Jessie’s idea,” says HD. “She bought a wig on the internet for 10 quid.” Originally, the script had simply called for Buckley’s character to don unspecified raver gear. “It’s the sadness of the walk of shame, that’s what we wanted to give her,” she explains. “There is something very sad that we all know about a girl in her party clothes in the bright light of day.”

One of Kaufman’s films that HD has seen is Synecdoche, New York, his sprawling 2008 directorial debut and arguably his masterpiece. The staggeringly intricate drama starred Philip Seymour Hoffman as Caden Cotard, a theater director who creates a massive stage production of his own life, casting actors to play himself and his loved ones who, in turn, cast actors to play them, resulting in an endlessly recursive series of plays within plays and a startling meditation on the purpose of life. To me, there are clear links between Synecdoche and How to Shoot a Ghost, as characters reckon with a world that is forgetting them, and come to recognize their transience.

Kaufman isn’t so sure. “As a piece of film, it’s very different than Synecdoche,” he points out. “I wouldn’t look at this film and think it was directed by the same person who directed Synecdoche.”

HD does see some similarities. “Caden is obsessed with mortality, and so is our film,” she says. “It's just the gaze is different. [The characters in Ghost are] trying to see the things around them, and he can’t even see that his wife has a full back tattoo of the devil! He’s never noticed, which is very comic, whereas these people are desperately gazing outwards for the world. They’re hungry for the world, and Caden can’t even see it.”

Kaufman counters: “He is hungry for the world, but he can’t see it. He’s trying to reconstruct the world, in a sort of ridiculous way.”

As they debate, I think of Hoffman, whose 2014 death from a drug overdose at the age of 46 shocked his fans and those who knew him. I ask Kaufman whether writing and thinking about mortality so deeply makes any sort of difference when real grief arrives with no warning.

“I wouldn’t say that that film helps me in any way,” he replies slowly. “I think poetry that I respond to helps me in that regard, stuff that’s about mortality can move me and be very helpful, and has been… but not that, not Synecdoche.”

HD is reminded of something. “I’ve got to read you this poem, Kevin,” she tells me. “It’s by a man named Sean Thomas Dougherty and it’s called ‘Why Bother?’ The whole poem is: ‘Because right now there is someone / Out there with / a wound in the exact shape / of your words.’” She turns to Kaufman: “I think maybe in that way Synecdoche might have helped… You just did it, and it was the shape of other people’s wounds.”

He nods, taking the compliment, but adds: “I’ve been told by people who like the film that it’s helped them in some way, but maybe it can’t help me, somehow.”

“Maybe it helped you through something,” suggests HD. “Maybe you’re less spiritually constipated. It’s like the s*** that you took. It got something out.”

Kaufman grins. “Yes. Synecdoche, New York is the s*** that I took,” he says. “Put that in your article, please.”

‘How to Shoot a Ghost’ screened at AFI Fest in Los Angeles. It is available to watch via the library-based streaming service Kanopy