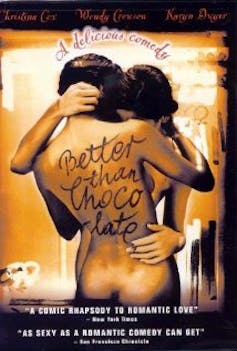

“If coming out of the closet was really as much fun as it is for the sexually adventurous youths in Better Than Chocolate, then everybody would be doing it, even straight people.”

So wrote film critic Bruce Kirkland in his 1999 review of the lesbian romantic comedy by Canadian filmmaker Anne Wheeler.

Kirkland pointed out that real life for queer and trans community members was “tougher, harsher and nastier” than portrayed in the 90-minute romp, but also wrote: “To hell with reality, at least for an hour-and-a-half. This movie is a little treasure and offers a lot of pleasure.”

The endearing rom-com won audience choice awards at a number of gay and lesbian film festivals, including in its hometown of Vancouver.

Today, more than a quarter century later, with hate crimes against queer and trans people on the rise and legal protections, especially in the United States, being threatened or ripped away, the film’s lens on romance — and the joy, safety and complications of being in community — may resonate with contemporary viewers and offer a brief reprieve from the heaviness of the political fight.

Like many Canadian lesbian-driven films from the 1990s, it also serves as an example of filmmakers working in queer communities to highlight once-censored voices, and reflects the sheer ingenuity and creative force of community collaboration in this moment — something that has been underrepresented in broader histories of queer and Canadian national cinema.

Whirlwind romance

In Better Than Chocolate, bookstore employee Maggie (Karyn Dwyer) and nomadic artist Kim (Christina Cox) start a whirlwind romance, moving in together within a matter of hours (echoing the classic U-Haul lesbian stereotype).

Their love story is complicated by the arrival of Maggie’s mother Lila (Wendy Crewson), a judgmental woman fresh off a divorce who doesn’t know her daughter is a lesbian. Comedic chaos ensues as the two young lovebirds navigate romantic, familial and community conflicts, all of which are neatly wrapped up by the end.

Though Better Than Chocolate may ultimately be a feel-good comedy, the film captures a community under attack from outside and within.

Skinheads harass Maggie and Kim, culminating in violence. Judy (Peter Outerbridge) is accosted for being transgender and is consistently misgendered by other lesbians.

The Canadian Border Services Agency purposefully targets neurotic bookstore owner, Frances (played by actor, author, playwright and Canadian lesbian icon Ann-Marie Macdonald), for selling queer literature.

Lesbian-centred 90s film

Better Than Chocolate is only one in a wave of lesbian-centred 90s films made in Canada. In this decade, creatives produced at least 12 narrative feature-length lesbian-centred films, several documentaries and over 400 short films.

Some echo Better Than Chocolate’s romantic tone, but the wave includes a diversity of genres – including erotic thrillers, family dramas and experimental dreamscapes.

Some of these films are well-recognized in the Canadian film canon, including Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996) and Patricia Rozema’s When Night is Falling (1995), while others have been largely forgotten and prove hard to access today, like Patricia Rivera Spencer’s Dreamers of the Day (1990) and Jeanne Crépeau’s Revoir Julie (1998).

Ecosystem behind lesbian Canadian film

Canadian economic, social and artistic contexts offered a vital creative ecosystem that facilitated such a vibrant era of lesbian-driven cinema.

Feminist filmmaking collectives in the 1970s — like Women in Focus (Vancouver), intervisions/ARC (Toronto) and Reel Life (Halifax) — alongside the launch of Studio D at the National Film Board of Canada in 1974 — provided dedicated space for training talent and for producing films about women’s issues.

Wheeler came up through Studio D, co-directing the studio’s first film in 1975.

Canadian artists also had access to several funding sources, including federal, provincial and local arts councils. Beginning in the late 80s, such funding sources were soliciting more diverse content, a result of community activism driven by marginalized artists.

Importantly, a growing network of queer film festivals aided the development of an invested audience willing to pay to watch queer stories.

From 1985 to 2000, at least 11 annual queer festivals were founded in Canada, including Reel Pride (Winnipeg, 1985); Out on Screen (Vancouver, 1988); image+nation (Montréal, 1989); London Lesbian Film Festival (London, 1991); and Inside Out (Toronto, 1991).

With increasing venues to screen queer work and growing audiences came the demand for more films.

A Vancouver lesbian story

Alongside the broader Canadian context, local contexts also encouraged more filmmakers to tell lesbian stories.

Wheeler had long been committed to making films about lesser-represented Western Canada. While most of her films were set in Alberta, Better Than Chocolate moved her focus to Vancouver and its local queer politics.

The dramatic subplot between bookstore owner Frances and the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) is a clear reference to the then-ongoing Supreme Court of Canada case involving Little Sister’s Book and Art Emporium in Vancouver.

Little Sister’s, a queer bookstore, had been targeted for years by the CBSA, which would delay shipments while confiscating and sometimes damaging materials that it considered obscene.

The film publicized the homophobia of the CBSA, with Frances comedically demanding to know why books such as Little Red Riding Hood had been confiscated.

As we discovered in our archival research, Janine Fuller, the manager of Little Sister’s, provided feedback on an early draft of the screenplay. A flyer from the film’s production company was also used to raise the visibility of the court case.

Local community ties

The film’s community ties extended further. As noted in archival documents and the film’s press package, Canadian trans activist and performance artist Star Maris inspired the filmmakers when crafting the character of Judy. Her song, “I’m Not a Fucking Drag Queen,” was solicited for use within the film.

Vancouver’s lesbian community was invited to participate as extras in a bar scene, with an advertisement stating, “This is an excellent opportunity to meet new friends, party with old ones, have much fun being in a movie.”

Finally, as Anne Wheeler told Eye Weekly in 1999: “Right from the development phase on, we had a group of 12 young lesbian women whom we consulted with and they told us very specifically what they did and didn’t want to see. … So we set out very intentionally to break the mould and dispose of the old perceptions about gay women.”

In returning to Better Than Chocolate and other films, queer audiences may find entertaining gems, but may also be reminded of the power of survival of queer communities.

Better Than Chocolate is now available on CTV. Don’t stop there! In addition to films named above, check out these other Canadian lesbian-centred 90s feature films.

Cat Swallows Parakeet and Speaks (1996)

Tamara de Szegheo Lang receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for the project "Bodies on Fire: Rekindling Canada’s Decade of Lesbian-Driven Filmmaking.”

Dan Vena receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for the project "Bodies on Fire: Rekindling Canada’s Decade of Lesbian-Driven Filmmaking.”

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.