The ancient Roman city of Pompeii has witnessed some pretty intense happenings over the centuries. In AD79, the nearby Vesuvius erupted and buried the city in volcanic ash. Nearly two millennia later, another elemental force of nature flexed its might within Pompeii’s ruins. For it was here, in the autumn of 1971, that Pink Floyd played the most remarkable concert of their career, four serious young long-hairs prising cosmic sounds from electric guitars, prehistoric synthesisers and hammered gongs, to split the sonic atom.

Half a century on – and 40 years after bassist/vocalist and arguable band-leader Roger Waters’ exit from the group – the watershed concert movie that chronicled this space-rock landmark has enjoyed a 21st-century makeover. The original 35mm negative has been restored frame by frame, its hallucinatory soundtrack given a Dolby Atmos remix by prog polymath and Porcupine Tree bandleader Steven Wilson, who declares it “the absolute zenith of Pink Floyd as an experimental rock band, the definitive statement of that era”.

Pink Floyd at Pompeii – MCMLXXII captures a group in transition. In their late Sixties days, fronted by doomed lysergic voyager Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd had been psychedelic pioneers as likely to perform three-minute psych-pop nuggets like “See Emily Play” on Top of the Pops as blow hippie minds with epic acid-rock improvisations at legendary London nightclub UFO. But Barrett’s 1968 breakdown, which followed months of heavy LSD use, signalled his exit from the group: a trauma the remaining members of Floyd – typical middle-class Englishmen of their generation – wouldn’t begin to process until their 1975 rumination on their fallen bandmate, “Shine On You Crazy Diamond”.

In the immediate aftermath of Barrett’s Icarus-like downfall, the remaining band members – drummer Nick Mason, keyboardist Richard Wright, guitarist David Gilmour and bassist Roger Waters – eschewed introspection and instead cast their eyes to the skies. Across albums like 1968’s A Saucerful of Secrets, unwieldy 1969 live/studio behemoth Ummagumma, 1970’s questing Atom Heart Mother and ambitious 1971 masterpiece Meddle, they ditched traditional song structures for excursions that might last the entirety of a vinyl LP side.

This music was often fiercely experimental and groundbreaking – Floyd were early adopters of any primitive synthesiser gear they could get their sweaty hands on – but nevertheless won a large, dedicated audience. The group toured heavily – Wilson estimates that, in this era, Floyd were “gigging 150-200 days of the year, and at their absolute peak”. When not on the road or recording albums of their own, they developed a lucrative side-hustle scoring art movies like Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970) and Barbet Schroeder’s La Vallée (1972).

The brainchild of filmmaker Adrian Maben, a British-born filmmaker based in France, Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii would combine Pink Floyd’s live prowess and their simpatico with countercultural cinema. A Floyd devotee, Maben pitched an appropriately atypical concert movie.

The genre was still in an embryonic state. Early breakthroughs like Woodstock and Monterey Pop often shifted focus from the onstage performances to young, beautiful and ecstatic attendees in the audience, to titillate and also to confirm that the filmmakers were chronicling Important Cultural Events. By contrast, Maben planned to focus on the group and their music, and very little else; there would be no audience, save Floyd’s road crew. This piqued the band’s interest, and also made for an easier sell to the officials at Pompeii, who could rest assured that the precious ruins would remain untouched by concertgoers.

“Nobody had ever made a concert movie without an audience,” says Wilson. “And it’s perfect for Floyd. They always had this sense of enigma and remove – they never catered for an audience or seemed concerned about them. Their whole thing was, they were making this music for themselves, whether or not anyone wanted to hear it.”

At Pompeii, Maben had his cameras glide around the musicians as they performed, delivering a uniquely intimate experience of the concert. “What I love about Pompeii is that the cameras are positioned among the band,” says Lana Topham, Pink Floyd’s in-house director of restoration, whose work makes this 54-year-old footage seem dazzlingly contemporary.

“Traditional concert movies are filmed from an audience standpoint. But here we feel closer to the performance, and get a glimpse of their relationship. Their focus is within themselves and with each other, not outward to an audience – and yet we feel more a part of it.”

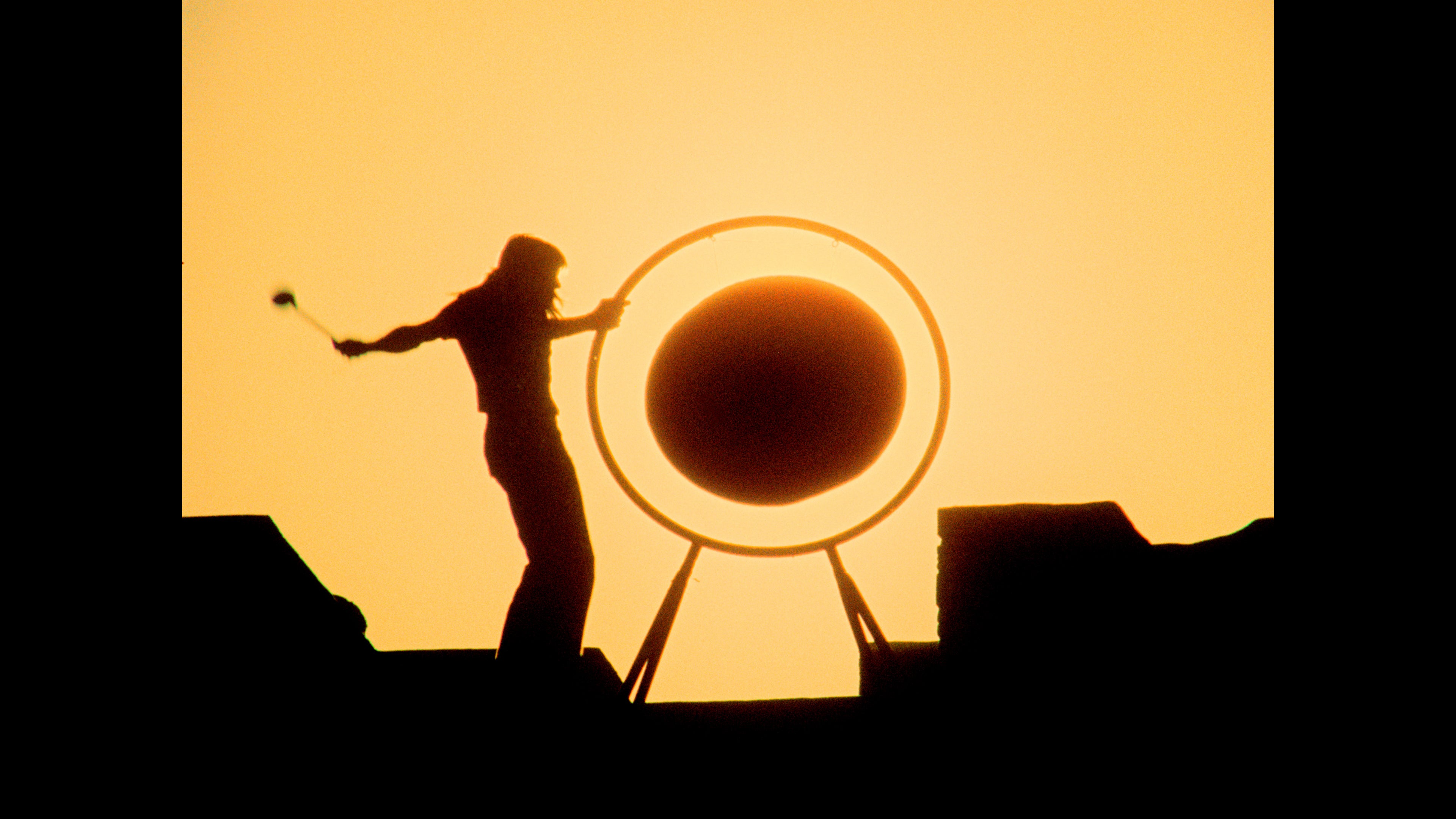

Anticipating Martin Scorsese’s work in The Last Waltz, Maben choreographed his cameras to capture key moments in the songs. On “A Saucerful of Secrets”, as the piece’s freeform excursion peaks, a camera follows Waters as he strides purposefully towards a gong and extravagantly bashes it, silhouetted against the sunset – the kind of iconic shot you simply don’t get by accident. Another camera, meanwhile, hovers before Gilmour, who’s cross-legged and shirtless in the sunshine, fiddling with his guitar and effects boxes, bare feet covered in sand. The sounds he creates, echoing and reverberating around the empty amphitheatre, are enough to beckon UFOs from the ether.

The intimacy of this footage was revelatory for Wilson when he first saw it at a revival at his local cinema in Chesham as a prog-curious 12-year-old growing up in Buckinghamshire. “It cemented my obsession with Floyd,” he says, “and it blew my mind, seeing those young, attractive, handsome men in Pompeii, playing this extraordinary, experimental and groundbreaking rock music. When you’re 12 years old and your reference points are the latest Iron Maiden album, it’s like something from another planet. You’re literally seeing them creating the vocabulary of experimental rock music as we now know it.”

This footage serves to both demystify and re-mystify Pink Floyd. For all the grand history of the locale where they’re performing, the band are framed by their massive touring flight cases, like a prosaic Stonehenge, stencilled with their logo, with somewhat-bored roadies lolling over them, and the sound-crew and their mixing desk firmly in view. We get to see how they create the fantastical sounds that populate their space-rock-era albums, a revelation akin to seeing a marionette’s strings or a ventriloquist’s lips move. But at the same time, Maben intercuts the cosmic crescendos with images of ancient sculptures and mosaics, with footage of bubbling lakes of lava, imbuing Floyd’s music with appropriate loftiness and heaviosity. “You might say it’s a little cheesy,” Wilson reasons. “But it works.”

Maben filmed further songs in a Paris television studio later in the year, editing the footage together for a 1972 premiere. The following year, believing the film still incomplete, he filmed further material at Abbey Road as Pink Floyd recorded their magnum opus, Dark Side of the Moon. Eavesdropping sessions, and lunchbreaks, and peeking behind the curtain to portray the men behind the music – Waters all combative and prickly, Wright ever the quiet one – the footage is engaging, revealing, and unselfconscious. “We do have infighting,” admits Mason. “We have some pretty good arguments from time to time,” agrees Gilmour.

The accompanying interviews at Abbey Road make Maben’s movie an indispensable portrait of a band experiencing metamorphosis. “We’re in danger of becoming a relic of the past,” grumbles Mason. “For some people, we represent their childhood in 1967, the underground in London, the free concert in Hyde Park. It’s an image we’d like to dispel.” Gilmour concurs: “Most people still think of us as a very drug-orientated group. Of course, we’re not.” Indeed, starting with Dark Side..., the group shifted away from the remnant psychedelia explored in Pompeii, focusing their songwriting on existential themes like death, madness and the meaning of life. After several years floating in space, Pink Floyd discovered transcendence in the earthbound, in the merely human, setting controls for the heart of the matter.

“This is a band that started off with a songwriter, Barrett, at their core,” Wilson says. “They lose Syd early on, and spend four or five years experimenting sonically and not worrying too much about the rigours of songwriting.” But then Waters assumes control – a move that isn’t without controversy, but helps shape Pink Floyd’s output throughout the rest of the Seventies. “Roger’s a brilliant architect of music,” Wilson continues. “He pulls the band towards these conceptual rock moves, tethering them to the structures and the architecture of the music. But they had to go through this space-rock period first, to arrive there.”

Pink Floyd’s imperial era – Dark Side, 1975’s Wish You Were Here, 1977’s Animals and 1979’s The Wall – won the group unimaginable success and acclaim, but it’s arguable whether it made them happy. Wilson, a Floyd superfan with intimate knowledge of bootleg live recordings from this era, says that with this upgrade in stardom, they began “struggling to get across what they’d been very at home playing in 2,000 to 3,000-seat theatres. They’re playing huge arenas in America, with idiot fans screaming at them all the way through the show, which gives Roger Waters the epiphany that led to The Wall. You can hear that they’re not as symbiotic as they used to be – they’re just not enjoying it. The success of Dark Side, musically, creatively and commercially, really destroys a lot of the magic they had in those space-rock years.”

To be that successful is the aim of every group. And once you’ve cracked it, it’s all over

Indeed, the phenomenal triumph of Dark Side presaged turbulent years for the group. Disputes over matters creative and personal – including how the members spent this new windfall of cash – prevailed, and Dark Side follow-up Wish You Were Here was marred by the group’s struggle for direction. Waters suspected they were now staying together out of “convenience, despite the big musical, political and philosophical differences that we had in the band”, telling Chris Salewicz in 1987 that Dark Side had “finished the Pink Floyd off once and for all. To be that successful is the aim of every group. And once you’ve cracked it, it’s all over.”

Waters grew increasingly disenchanted; the group’s 1979 double album The Wall was a direct response to dispiriting tours of the US, before audiences who seemed disconnected from the music the band were playing. Following 1983’s The Final Cut, Waters believed Pink Floyd were done, and sued to dissolve the group and prevent the remaining members from continuing to use the name.

Nevertheless, Floyd’s first Waters-less album, A Momentary Lapse of Reason, arrived in 1987; in December of that year, a legal agreement was reached that allowed Gilmour and Mason to continue as Pink Floyd, which they did; a 2022 single in support of Ukraine, “Hey, Hey, Rise Up”, is the most recent Pink Floyd release, their first since 2014 farewell album The Endless River. Despite the legal agreement, enmity continued to crackle between Waters and Gilmour, though they put their differences aside in 2005 for Pink Floyd’s performance at the Live 8 benefit concert, Waters playing alongside Gilmour, Mason and Wright for the first time in almost a quarter of a century. Barrett died the following year, and Wright passed away in September 2008.

But we’ll always have Pompeii, and the magic captured on Maben’s movie, which remains Wilson’s most treasured Floyd artefact. “I would happily stand up in a court of law and say Dark Side of the Moon is Pink Floyd’s masterpiece, the pre-eminent masterpiece of conceptual rock, bar none,” he offers. “But my favourite era is when they're still exploring, when they’re not sure what they are, and still have that sense of curiosity. There’s something magical about that, and Pink Floyd at Pompeii – MCMLXXII is the definitive statement of that era.”

* ‘Pink Floyd at Pompeii - MCMLXXII’ is released by Sony Music Vision and Trafalgar Releasing in cinemas & IMAX® worldwide. The live album is available on multiple formats from 2 May