More than 50 years ago, when I was a junior curatorial assistant at the Art Gallery of NSW, I had the daunting experience of hanging the annual Archibald, Wynne and Sulman prizes.

At the time the professional staff held the exhibitions in such disregard, they complained about the news media’s interest in this mediocrity while ignoring more worthy events.

Attitudes changed in the 1980s with the late director Edmund Capon, who recognised popularity was an asset – not a disadvantage.

Capon raised the prize money with sponsorships and started charging the public to see the winners. His strategy proved so successful that the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman exhibitions are now a significant source of revenue for the gallery.

This year, the highly experienced Beatrice Gralton, Senior Curator of Contemporary Australian Art, has curated the exhibitions with support from a crew of more than 40 colleagues.

Packing Room Prize goes to Abdul Abdullah

In the 1970s, the media was refused access to the exhibitions until just before the winner was announced. Now it is actively courted with a public viewing of the works that survive the rigorous culling process.

This takes place a week before the final judging, when the Packing Room Prize is announced. The changing status of this prize is also evidenced by changing personnel. Those who did the physical work of packing and loading artworks in the past were not expected to know much about art – and often gave the prize to paintings that would otherwise not be hung.

In 2025, the specialist installation crew that handles the portraits in the packing room are most likely to be professional artists themselves – a reminder that most artists need another gig to stay afloat.

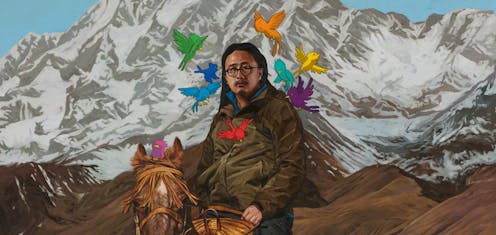

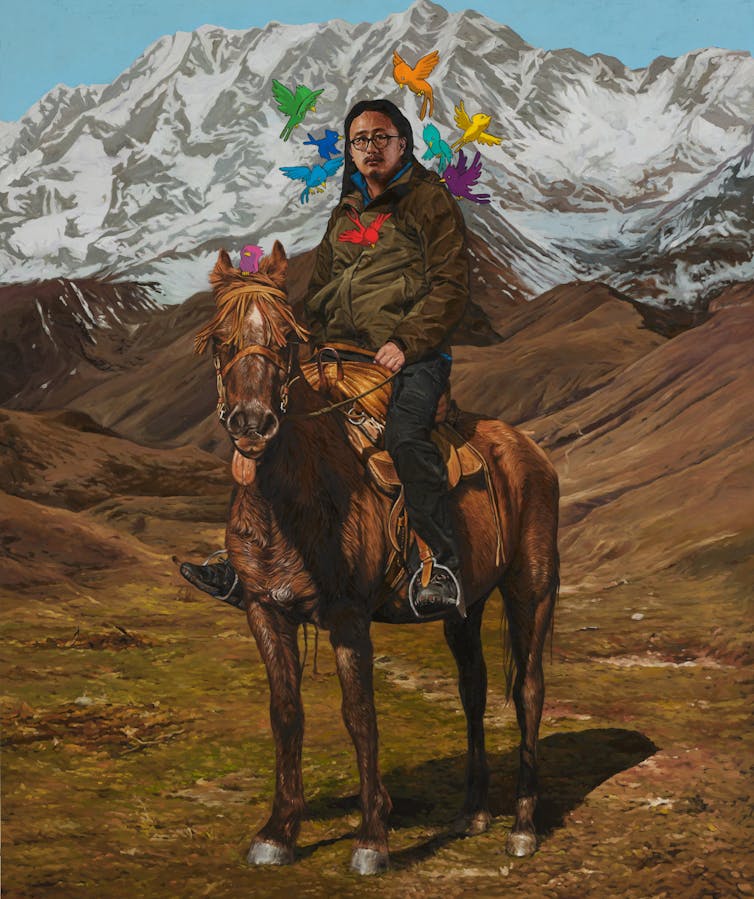

This year’s Packing Room Prize winner is Abdul Abdullah’s portrait of fellow artist Jason Phu, No mountain high enough. There is a glorious irony in this, as Abdullah has long been a critic of the self-important art establishment.

His work is a riff on the heroic paintings of 19th century landscapes, except for the flock of twittering birds that surround the head of the solitary rider, a bit like a halo.

His subject, fellow artist Phu, has to be seen as a serious contender for the main prize, which will be announced on May 9. Phu’s portrait of actor Hugo Weaving – older hugo from the future fighting hugo from right now in a swamp and all the frogs and insects and fish and flowers now look on – has both the humour and energy that has long characterised his work.

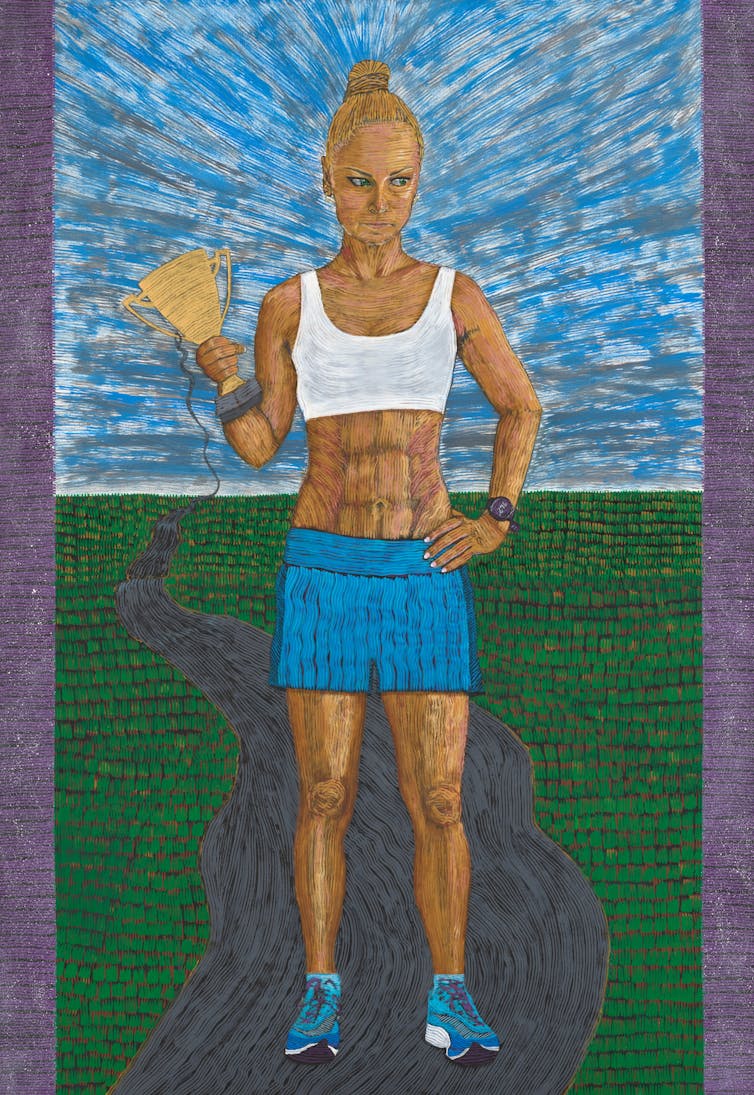

But there are many serious contenders for this year’s prize. Kurdish refugee Mostafa Azimitabar first exhibited in the Archibald in 2022, with a self-portrait painted in coffee, with a toothbrush. Art became his refuge during the many years he spent incarcerated as an asylum seeker.

He still uses a toothbrush, but has used paint for his wonderfully fierce painting of a taut Grace Tame, appropriately named The definition of hope.

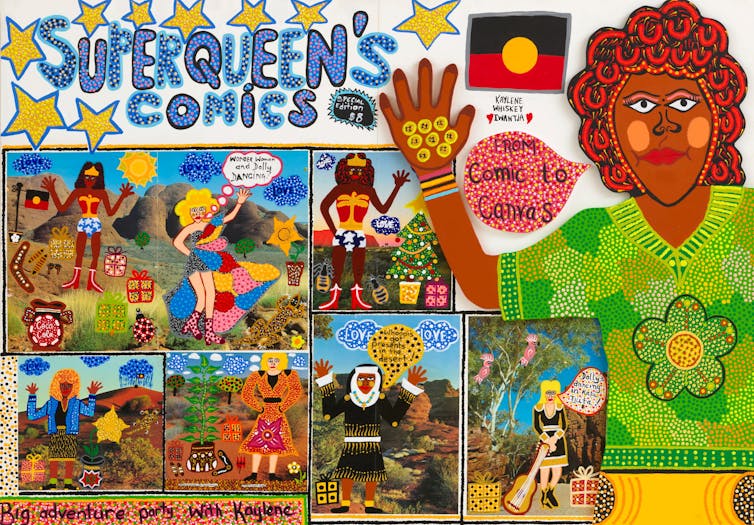

Then there’s Kaylene Whiskey’s delightful self-portrait From comic to canvas, which manages to include images of her heroines, Dolly Parton and Tina Turner.

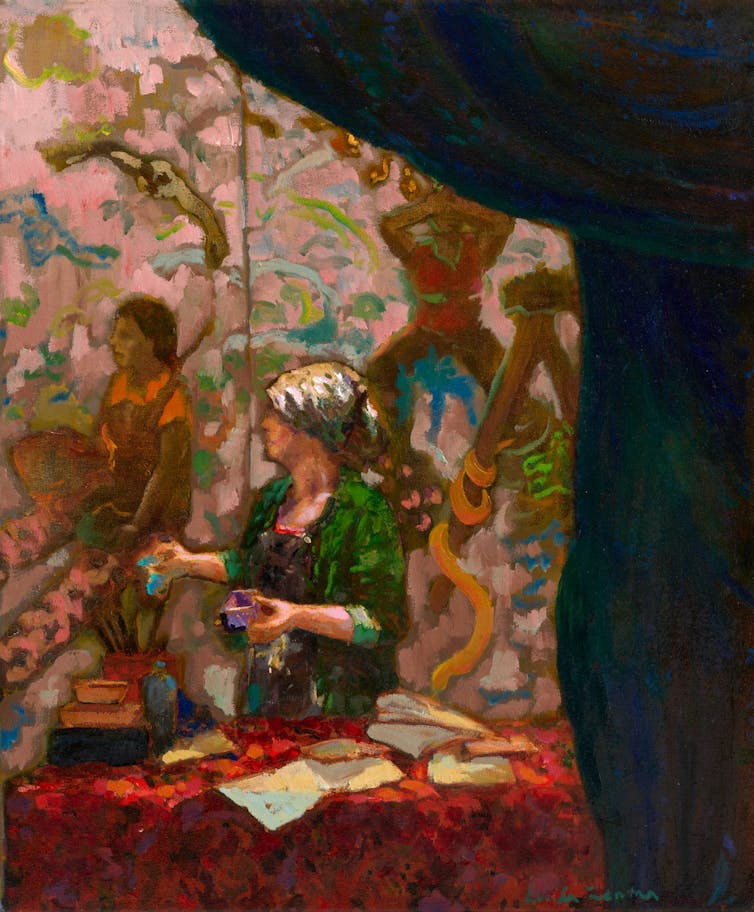

Not all works are so strident, however. Lucila Zentner’s Wendy in the gallery, is a subdued portrait of fellow artist Wendy Sharpe, placing her in the context of her art, almost as a decoration.

A suite of diverse storytelling

As is spelt out in J.F. Archibald’s will, the judges of the Archibald Prize must be the trustees of the gallery, and no one else may interfere in their decision.

However, for decades after a spectacular court case resulting from the 1943 Archibald, the trustees were so nervous of litigation that the final judging was administered by the NSW electoral office. In a court case in 1944, plaintiffs claimed the trustees’ 1943 decision was a breach of trust as the winning painting wasn’t a portrait. And one trustee claimed he had accidentally voted for the winner, thinking he was voting against it.

Today, all decisions are made in-house. Court cases have been fought over whether entries were paintings (or not), painted from life (or not), selected by the trustees (or not). In 1990 Sidney Nolan had to withdraw his entry after it was pointed out he could not be described as a “resident in Australasia for 12 months preceding the date of entry”.

But once the entry conditions are met, the curator has a free hand. This year, Gralton has hung all three exhibitions on the premise they are “about stories and storytelling”.

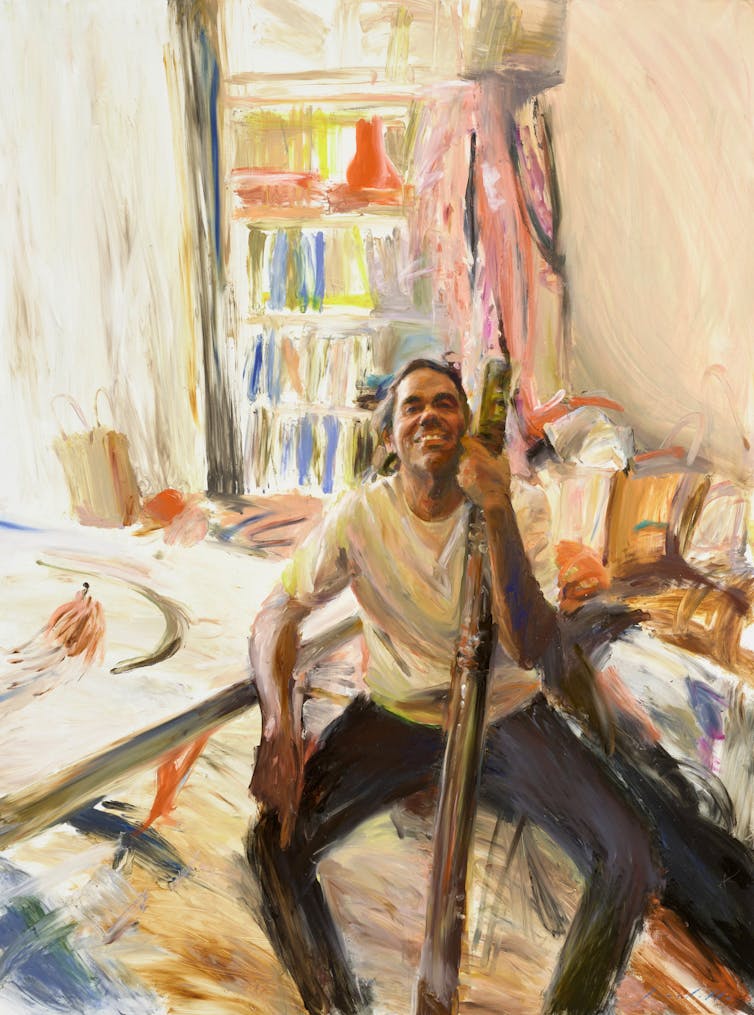

There is the joyous extravagance of Meagan Pelham’s Magic Nikki and Charlie fancy pants party … Djaaaaaaaay, the stark analysis of Chris O'Doherty’s Self-portrait with nose tube, and the wildly painterly approach of Loribelle Spirovski’s Finger painting of William Barton.

In the Sulman prize exhibition – awarded for best subject painting, genre painting or mural project – the once academic modernist Mitch Cairns has gone full conceptual with his stark Narrow cast (studio mural). It looks like something straight out of the 1970s Art & Language movement.

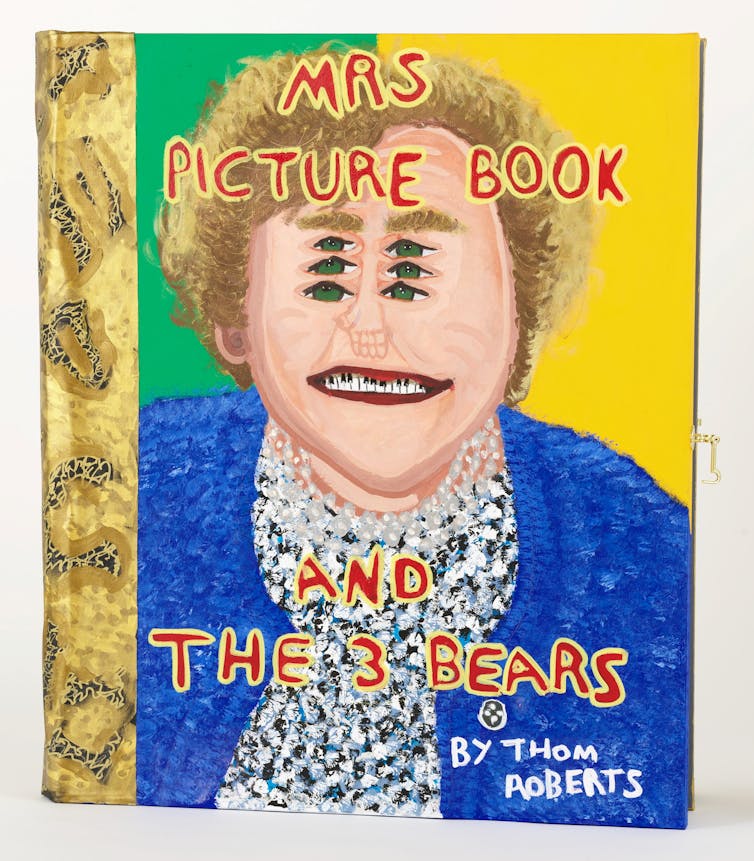

But my money is on Thom Roberts’ Mrs Picture Book and the three bears, a painting as a book, in three canvases.

The Wynne prize is for both Australian landscapes and sculptures. This year there are many three-dimensional works, ranging from the elaborate Billy Bain to the almost agonised restraint of Heather B. Swann.

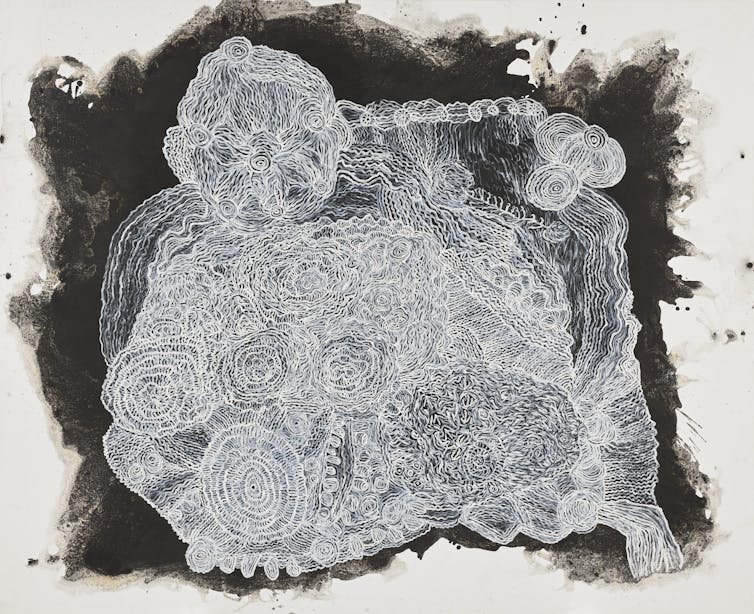

Lucy Culliton’s Cliff Hole, Bottom Bullock, hangs alongside Betty Muffler’s Ngangkaṟi Ngura – healing Country – both paintings of Country.

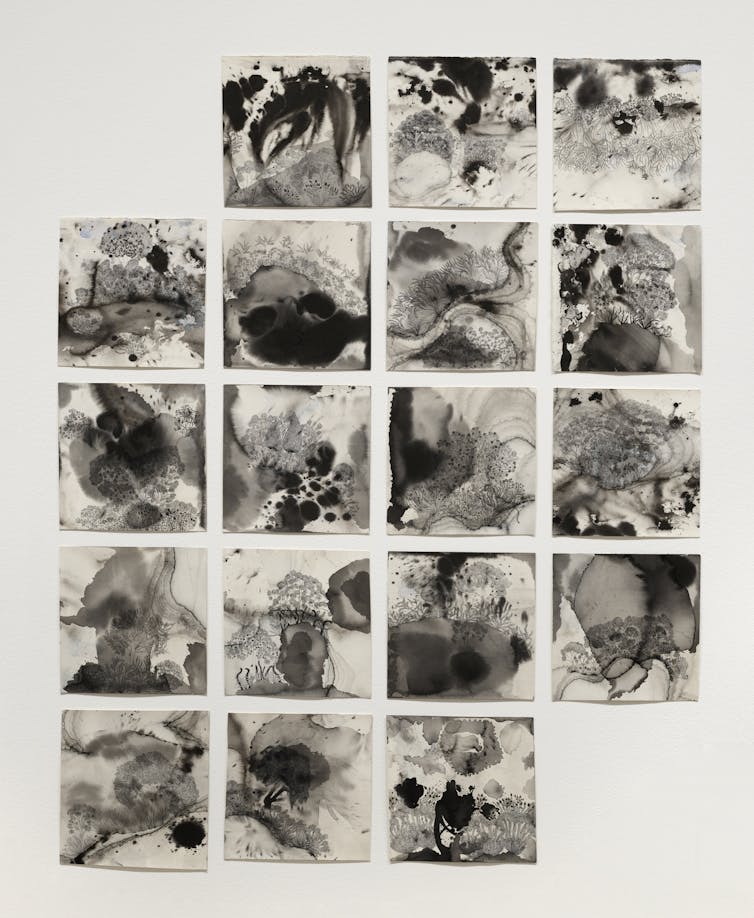

Then there is Mehwish Iqbal’s beautiful, delicate Zameen muqaddas (sacred earth), a pen and ink contrast of fine botanical drawing and delicate wash, all on handmade paper.

While artist Elizabeth Pulie has already judged the Sulman prize, the judging for the Archibald and Wynne will be finalised early morning on May 9. This year’s result is anyone’s guess.

Joanna Mendelssohn has in the past received funding from the ARC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.