Wu Guanzhong, the Paris-trained Chinese artist, returned to China in 1950, shortly after the Communists took power, and stayed there the rest of his long life. By the time he died in 2010 at the age of 90, he had become one of the most celebrated Chinese artists of his generation.

His paintings frequently tested records for Chinese art in auctions, his reputation reinforced by major exhibitions, and Asian museums received gratefully his personal donations of hundreds of works.

Hong Kong museum now boasts largest collection of Wu Guanzhong work

Posthumously, efforts to lionise him continue. On August 22, the Hong Kong Museum of Art said it would open a permanent Wu Guanzhong Art Gallery next year after it received an unprecedented sixth donation of works from the Wu estate.

The addition of Wu’s last works, significant sketches and personal memorabilia has brought the Hong Kong museum’s collection to around 450 pieces.

In 2016, the Singapore National Gallery also opened its own Wu Guanzhong gallery to permanently showcase the highlights of its collection of more than 100 of the artist’s works. A new exhibition, “Wu Guanzhong: Expressions of Pen & Palette”, opened there on Friday.

Elsewhere, there are significant collections at the Shanghai Art Museum and Zhejiang Art Museum in China, and they too have been featured in a number of exhibitions since Wu died.

Recognition came late to Wu. It was during the 1980s, when he was in his fifties, that collectors in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia began to take an interest in his art. A breakthrough was a 1992 exhibition at the British Museum – the first solo show for a living Chinese artist.

Auction prices for his paintings surpassed HK$1 million around the turn of the millennium. His Zhou Village (1997) was sold for a staggering HK$236 million (US$30.4 million) in 2016.

He certainly paid his dues.

Zao Wou-Ki, Chu Teh-chun and Wu had studied Western art under Lin Fengmian at the Academy of Art in Hangzhou, eastern China, and all ended up in Paris at about the same time in the 1940s and ’50s.

The lives of the “Three Musketeers” of Chinese modernism diverged sharply – because Wu was the only one of them to move back to China permanently.

He suffered great physical hardship (hepatitis and an untreated prolapsed haemorrhoid) before and during the Cultural Revolution, when he and other intellectuals were sent to the countryside to labour on farms. He and his family lived in abject poverty for years while he held firm to his artistic principles – which were never in tune with those of the Chinese mainstream.

Wu was devoted to the modernisation of Chinese painting, and a deep attachment to his native cultural traditions worked with Western influences to spark a vibrant, poetic, and thoroughly original style.

In his small studio at home in Beijing, he painted with both oil paint and Chinese ink. His artistic heroes came equally from both worlds: the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh and the Chinese writer Lu Xun.

Zao Wou-Ki: Chinese painter who became a Western master

He would have loved to paint portraits, but switched to landscapes and buildings because the Communist Party banned nudes and preferred images of glorified workers. So he travelled widely with his easel in search of subject matter that, as he said, would move him with beauty and appeal to ordinary people.

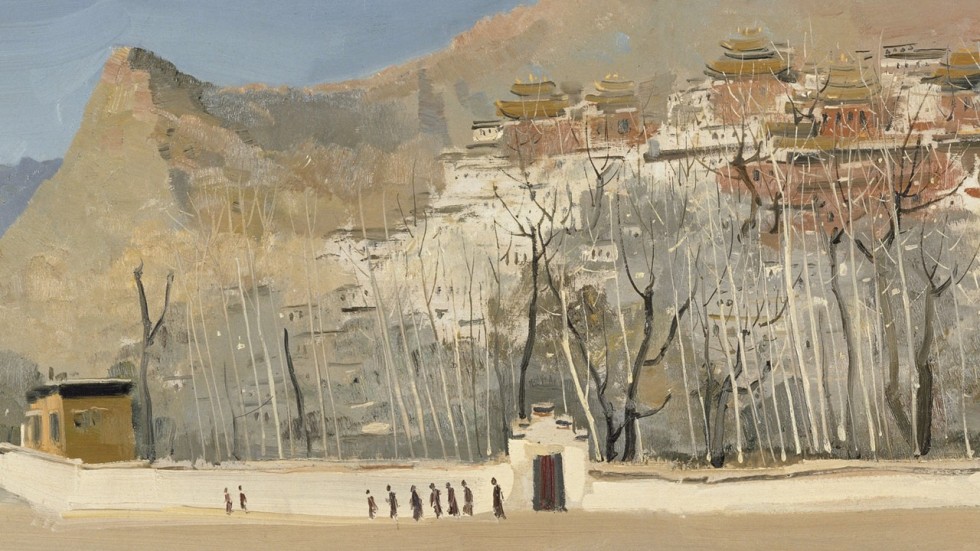

He painted Tibet, ruins of ancient cities along the Silk Road, California and, during his numerous trips to Hong Kong, the city’s skyscrapers, Victoria Harbour and its bustling street scenes.

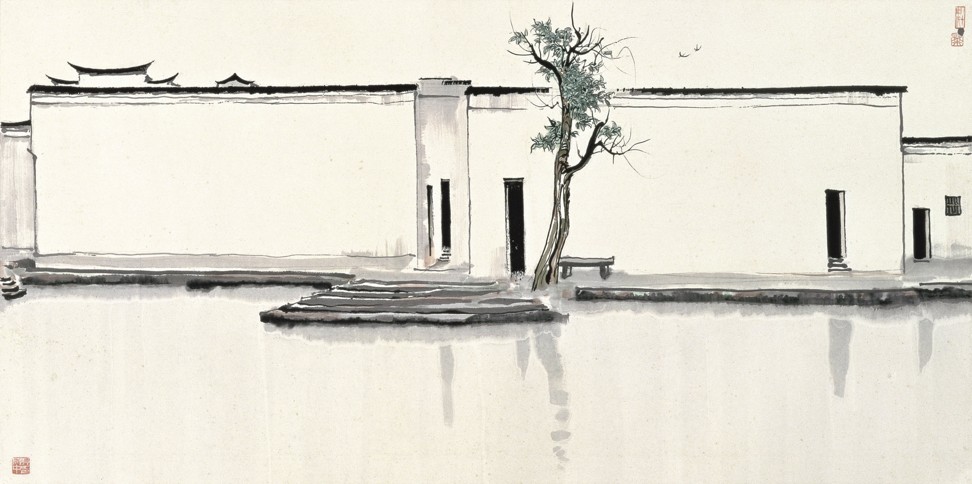

But his best known works were undoubtedly the ones based on his beloved Jiangnan region near Shanghai. Both Wu and Lu trace their ancestry to that part of China where, to this day, historic towns are dominated by a traditional building style featuring grey tiled roofs and white walls.

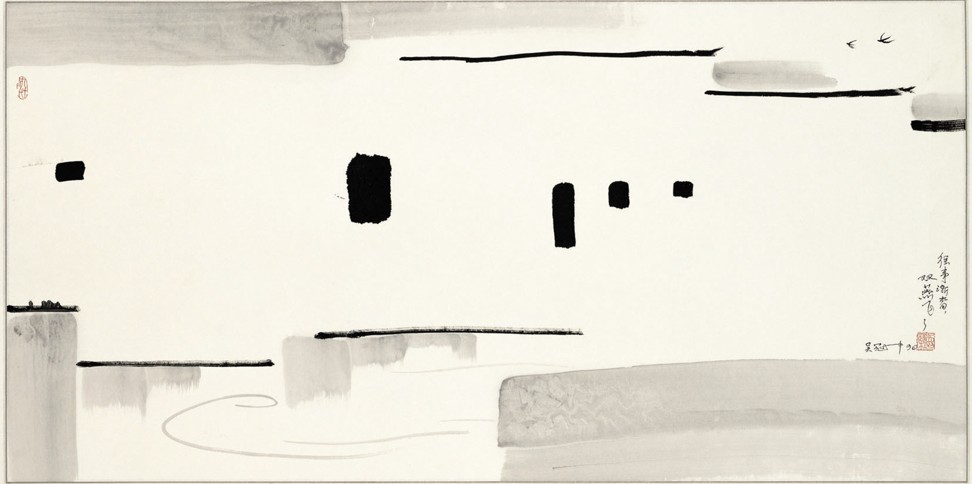

In Twin Swallows (1981), Former Residence of Qiu Jin (1988) and Reminiscence of Jiangnan (1996) – all in the Hong Kong Museum of Art’s collection – Wu left most of the canvas blank, a nod to the Chinese tradition of liubai (preserve the white), and the slightest application of colours disrupts the monochromatic calm – the green and brown of a tree, the red artist’s seals in the corners.

While the subject matter of the three paintings is similar, Wu employed vastly different perspectives, brush strokes and degrees of abstraction in each. His works were often reminiscent of cubism, and his application of dots and lines – such as his wisteria series from the 1990s – combined traditional Chinese brushwork with influences from the likes of Joan Miro and American abstract expressionists.

He always insisted that art should not be for the elite, hence his frequent donations to museums. These were also a canny move to establish his reputation, and suggested an unshakeable confidence in his own work.

How China’s most bankable artist, Zeng Fanzhi, found new way to make art

His self-assurance often came through in sharp-tongued criticism of other Chinese artists, and he made powerful enemies who objected to his insistence that artists should observe the primacy of beauty, not ideology, media or concepts.

First, he was denounced as a teacher at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in the 1950s for promoting Western bourgeois values and for failing to adhere to the evolving style of socialist realism, which became the only style of painting the Communist Party sanctioned. He was eventually ousted by Xu Beihong, the academy’s president, who Wu said was “blind to beauty”.

Later, his landscapes were deemed irrelevant as younger artists in the 1980s directly referenced China’s social changes. Even after attaining international success in the 1980s and 1990s, he remained a controversial figure in China, criticising traditional ink artists for their rigid notions and calling for the abolition of the powerful and acquiescent China Artists Association.

In turn, traditional artists labelled Wu a Chinese-Western hybrid who was master of none.

The antagonism he faced in China contrasted with the positive reception he had in Hong Kong, a city he was particularly fond of visiting because his mentor, Lin, had settled there after 1977. He liked the fact that the former British colony was half Western and half Chinese.

Local collectors were among the first to buy his paintings when Wu took part in exhibitions in Shenzhen and Guangzhou, cities in southern China, around the time of China’s economic liberalisation.

In 1979, the famous art historian Michael Sullivan mentioned Wu in a talk in Hong Kong on post-revolution Chinese art – the first Western academic to acknowledge his significance. Then, in 1992, the redoubtable designer Lo Kai-yin, her sister Marina Lo Kai-man and art dealer Fong Yuk-yan (owner of Yan Gallery and father of actor Alex Fong Lik-sun) convinced the British Museum to give Wu a solo exhibition.

Chinese artist Xu Bing on Western art and modern China

In 1995, the Hong Kong Museum of Art held the first of three major solo exhibitions curated by Szeto Yuen-kit, the museum’s head of Chinese painting and calligraphy, who developed a special rapport with Wu and remained close to him for the rest of the artist’s life.

That special relationship was again confirmed on August 22, when Wu’s eldest son, Wu Keyu, officially handed over the latest donations to the museum to the head of Hong Kong’s administration, Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, at a red-carpet ceremony at Government House.

The opening of the Hong Kong Wu Guanzhong Gallery next year will coincide with the centenary of the artist’s birth.