It is often thought that wild dance clubs only arrived in Spain in the late 1970s and 80s, once the dictatorship ended and the country had been freed from the ghosts of Franco’s conservatism. But evidence shows that 100 years ago (or even more) so-called “dancings” were happening in Madrid and Barcelona. In these clubs, boys and girls went to move their bodies for hours – and to find someone to end the evening with.

The dictatorship closed down many of them and severely condemned the free and carefree behaviour they harboured. However, traces of their existence can be found today in the country’s historical archives.

Dance fever

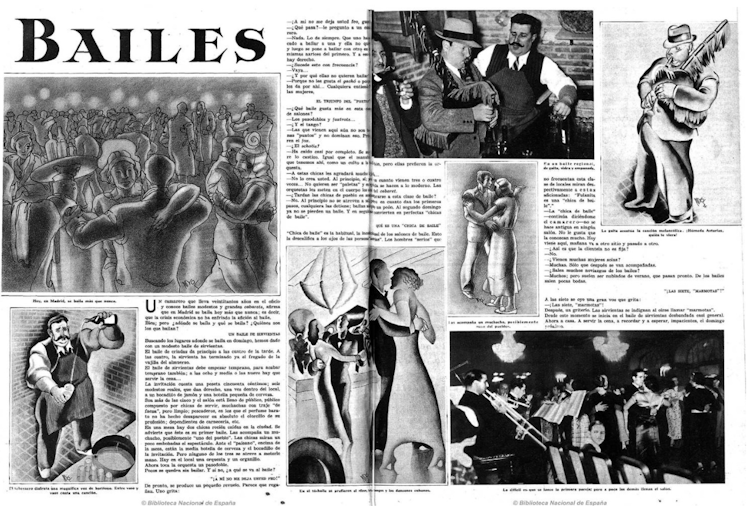

The origin of these dance halls goes back to the interwar years (1918-1936). During those frenetic decades, big cities started to host new places for fun and socialising, such as cinemas, cabarets, modern bars and also commercial dances.

At that time, urban youth lived immersed in the “dance craze”, an obsession with dancing that followed the opening of the first dancings “for all audiences”, which, like today, were accessible by paying an entrance fee (cheap, in general, and even more so for girls).

In Madrid, before the outbreak of the civil war, there were around 50 such theatres.

The newspapers of the time were quick to echo this new fashion which, they said, had duped the youth:

What does it matter to those infinite, innumerable crowds of dancers stubbornly parodying totemic monsters suddenly and fantastically animated by African tam-tam or Yankee jazz, the spiritual and aesthetic problem of their respective homelands? Don’t talk to them about books, or art, or science, or nature, or morality, or home, or love other than flirtations in dancing or the cinema, the stadium bleachers and the front seat of the car. What matters to them is to disjoint the body, to seek the grotesque arrhythmia of the forms, to obey the stridencies of what is already very accurately called “a cocktail of music”.

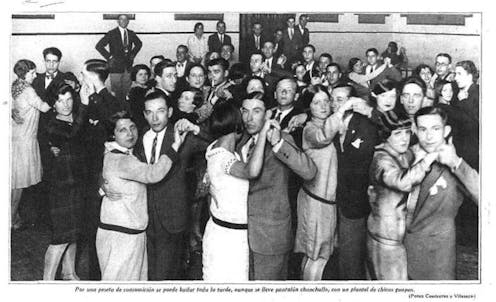

These commercial dances were closed premises in which, daily in the evenings, and all day on Sundays and holidays, dancings called populares or de modistillas were organised. They were animated by the music of a barrel organ, a gramophone or a modern tango orchestra or jazz band. Halls might be humble or grand but all were defined by a large central dance floor. This could be surrounded by wooden benches or couches, tables, lighting, mirrors, carpets, curtains and other decorative elements, in the finest examples.

The love of dancing among young people was not a phenomenon exclusive to the interwar years. Earlier, open-air dances were often organised in picnic areas, parks and open fields. But the appearance of the new commercial halls transformed these informal celebrations – especially because, unlike their predecessors, the new dancings were exclusively for young people.

Boys and girls from very different neighbourhoods of the city went to them to spend time partying far from the gaze of their families. This allowed them to let themselves be carried away by the unbridled rhythms of the new modern music and also to surrender to the weaknesses of the flesh.

Dancing – and flirting

The new commercial dance halls unleashed open and uninhibited amorous and sexual behaviour among popular youth. To begin with, the very nature of these venues demanded close encounters and contact between boys and girls.

Even if you went there alone, you would dance with a partner and finding this partner was the mission of every young man. So much so that for those who were not very fortunate, the service of “taxi-girls” was introduced in some venues: girls who were hired by the venue’s impresario to dance with the unpaired.

Boys and girls took advantage of their proximity to the opposite sex to exchange glances, get closer, talk and touch each other. They went to flirt and find a partner without needing the approval of their parents.

Dances thus became true incubators of formal courtships, but also of transient romances or “express boyfriends”, as they were called at the time. As the magazine Crónica pointed out in July 1936:

“At these dances of our democratic era, where you can find a partner without having to be introduced, […] you girls of today dance with this boy whom you did not know yesterday and you do not know what he may be for you tomorrow.”

Although at first sight it might seem an insignificant phenomenon, the appearance of these dancings brought about a cultural change of enormous importance. By making these new forms of meeting and contact between young people possible, these venues helped to widen the margins of what was considered normal or respectable in terms of flirting and erotic exchanges within leisure spaces, and also outside them. Although they did not know it, the foxtrot and tango steps those young people took were helping to build the new culture of modern entertainment.

Cristina de Pedro Álvarez receives funding from Complutense University of Madrid.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.