There is a well-known quotation — variously attributed to American Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, film producer Samuel Goldwyn and golfer Gary Player — along the lines of: “The harder I work the luckier I get.” Although often seen simply as a riposte to those that insist that some people succeed by “getting the breaks”, it is actually sound common sense. So, yes, somebody might be offered a high-profile job, but probably only if they have acquired the necessary qualifications by attending impressive educational establishments. Or they could become a top-flight athlete, but only by applying themselves and making sacrifices in order to best fulfil the potential that nature has given them, and so get snapped up by a leading team. Just as there are plenty of bright children who flunk out without ever making a mark in the world there are plenty of sports people who — through a variety of reasons — never make the most of their talents.

But it is one thing to accept that “blind luck” plays at best only a limited role in individuals’ success and quite another to know how to “make your luck.” This is the hole that Christian Busch, a well-known academic focused on innovation, purpose-driven leadership and serendipity, is seeking to fill with his book Connect The Dots. A new and updated version of his earlier book, The Serendipity Mindset, the trickiness of the approach is indicated by the subtitle, The Art and Science of Creating Good Luck. In other words, processes and plans can be put in place, but for something special to happen other factors have to be involved. As Busch puts it, “It’s not only about showing up, it’s about how we show up. If you go to the gym and run into (what could have been) the love of your life but haven’t showered for a couple of days or are in a foul mood, your probability of ending up together might be lower than if you are in a better place.”

For organizations, he adds, this means developing a mentality that allows for the integration, building and reconfiguring of “internal and external competencies to facilitate an environment in which unexpected discoveries are enabled and nurtured.” That such situations are rare is indicated by the fact that the tale of how the industrial company 3M discovered and developed Post-it notes — told in the book — has become legendary. But with the pandemic demonstrating better than any lecture by a management guru or consultant how uncertain and unpredictable the future is, it is all the more important to have some understanding of how to create the conditions in which serendipity can happen.

Early on in the book, Busch describes three basic types of serendipity. These are:

Archimedes serendipity — an unexpected way of solving a problem you wanted to solve, demonstrated by the story of the Greek mathematician — while taking a bath — accidentally discovering that the amount of water displaced was governed by the weight of the object being immersed.

Post-it note serendipity — an unexpected solution to a different problem from the one you wanted to solve, demonstrated by researcher Spencer Silver looking for a stronger glue, but actually finding something completely different — a weaker glue that turned out to be perfect for an entirely new product line.

Thunderbolt serendipity — an effortless solution to an unexpected or unrealised problem, as when a group of people attending a rock concert was annoyed by the behaviour of other concertgoers who were not attending solely to the music and came up with the idea of intimate gigs played in people’s front rooms.

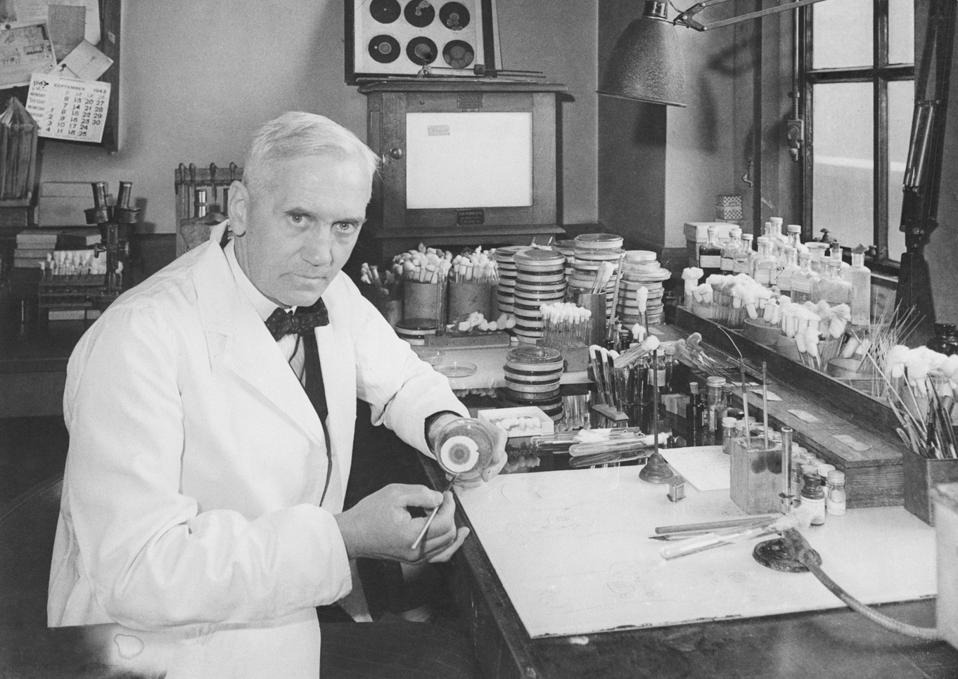

But he also points out that not every example will fit neatly into a category and in fact warns that attempting to categorise is “one of the things that can kill serendipity stone dead.” One of those that does not fit into a neat group is one of the greatest examples of serendipity — Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin. Fleming, as every school child knows, was researching the bacterium staphylococcus and one morning returned to his laboratory to find that one of his Petri dishes containing bacteria samples had been left uncovered. Something unexpected happened — there as a blue-green mould was growing on the dish and in the space around the mould the original bacteria had disappeared. Fleming was obviously not trying to discover antibiotics since the concept was not known back in the 1920s, but the crucial element was his behaviour. Rather than simply throwing out the sample he was curious and started on the research that would inevitably lead to the antibiotics that we all use today.

Busch insists that Fleming was not “just lucky.” He made the key decision to — in the title of the book — “connect the dots.” And it is this ability to see links and opportunities that he regards as essential for organizations confronting an uncertain future. Of course, as an academic, he has all sorts of explanations for how this works and techniques that can be adopted to, as he puts it, “create more meaningful accidents — and to make more accidents meaningful.” But in the end it seems it all comes down to individuals and organizations being more inquisitive and open to exploring things that might, at first glance, look like leading nowhere.