For the past two years, Tesla has been embroiled in a bitter dispute with the Swedish labour union IF Metall. It is of a scale that the union hasn’t witnessed since the 1930s.

At the heart of the dispute is Tesla’s refusal to sign a collective bargaining agreement. This is a pillar of the “Swedish model” of labour relations, which is prized by Sweden’s citizens due to its perceived contribution to social wellbeing and shared prosperity.

Instead, Tesla has opted to circumvent striking union workers and bring its cars into the country using non-unionised labour and labour from neighbouring countries. Tesla’s actions to undermine a system that Sweden strongly supports are what we call “anti-societal”. That is, they might be said to undermine democratic norms and the broader public interest.

More broadly, it isn’t unusual to see corporations acting in ways that negatively affect the public interest, with effects such as environmental degradation, poor working conditions or violations of anti-trust laws. Multinational corporations are often in the news for violating or avoiding government regulations and working behind the scenes to influence regulation to their advantage.

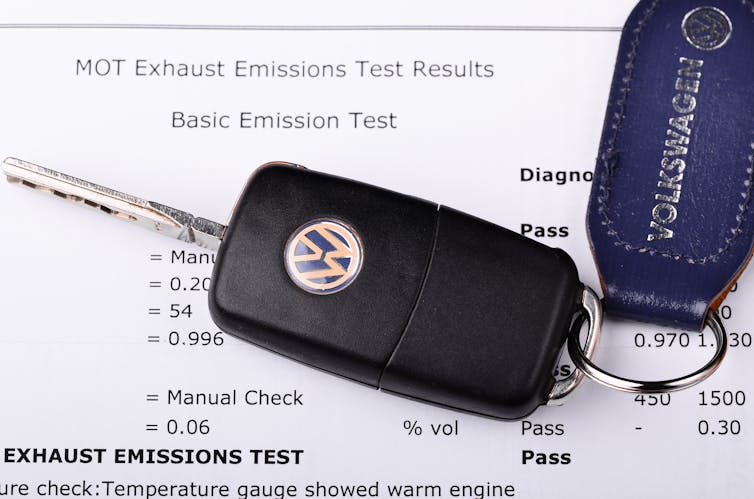

Among many examples is the Volkswagen group’s “Dieselgate” emissions scandal. The German carmaker cheated on vehicle tests to make diesel cars seem less polluting than they were in reality. The company later acknowledged it had “screwed up” and breached customers’ trust.

And it is believed that oil and gas giant Exxon had evidence in the 1970s that fossil fuels contribute to climate change, but mounted a a campaign of disinformation in order to stifle regulation of their products. (In 2021, Exxon CEO Darren Woods told US politicians that the company “does not spread disinformation regarding climate change”.)

These examples raise the question of why corporations engage in activities against the public interest. Yet browse through any standard textbook used in a university business or management course, and you will struggle to find answers.

Instead, for several decades the standard viewpoint has been that multinational corporations are mainly economic entities without any particular interest in doing either harm or good. Any anti-societal corporate behaviour has typically been chalked up to a few “bad apples”.

The fact that corporations have political power and systematically use it in their interests in ways that harm society has been largely left out of the picture.

Our recent research shows that the underlying nature of the global economy can influence any corporation to behave anti-societally. We argue that under certain circumstances, a corporation like Tesla might face a threat that compromises its market position, assets or even its existence.

IF Metall, for example, poses a significant threat to Tesla’s business model. If the Swedish trade union wins this dispute it could strengthen the bargaining position of trade unions across Europe. In this case, a corporation like Tesla will exert its power to protect itself. But this often comes with negative consequences for society.

We call this the “self-preservation perspective” of the multinational corporation. It illuminates the ways in which corporations use political power to their advantage, often to society’s cost.

The balance of power

The self-preservation perspective can help people to understand how corporate political power should be challenged through both regulation and activism. Trade union action, for instance, can act as a powerful political force to balance corporate power.

The idea of “self-preservation” comes from international relations theory and an overlooked argument by the late Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith .These suggest that any organisation – a nation state or a multinational corporation – will seek primarily to preserve itself in the face of threats.

We apply the idea of self-preservation to modern multinational corporations that seek to survive in a global economy marked by fierce competition and complex regulation.

This perspective predicts that, when faced with a regulatory threat, a multinational corporation will weigh up four strategic options.

First, it may try to influence the regulation through sometimes ethically questionable political activities. Second, it may consider avoiding or ignoring the regulation by exploiting loopholes or by taking strategic legal action. Third, it can decide to comply with the regulation. And last, it can think about exiting the market altogether.

We predict that the corporation’s choice depends on its relative level of political power and resources, as well as the profitability of the market it is operating in. However, it also depends on how powerful it is in relation to governments, trade unions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

If government enforcement or societal pressure are very strong, this may steer a corporation toward adapting to the regulation, rather than more negative influencing or avoiding behaviour. One example is Apple’s recent changes to its App Store rules in Europe, to comply with the European Union’s Digital Markets Act.

In the case of Tesla versus the Swedish union, Tesla has exerted its power to avoid regulation. In doing so it has considered the scale of the threat to its business model across Europe and its perceived power relative to the trade union. This possibly stems from Tesla’s strong ties to the technology sector, where engagement with unions is often seen as an unnecessary threat to innovation.

If Tesla’s avoidance strategy succeeds, it would effectively dissolve the Swedish model, creating a system that’s less secure for workers. From our self-preservation perspective, IF Metall’s success in the dispute will depend on how well – and how widely – the unions, government and citizens can galvanise opposition. By balancing corporate power in this way, societies might hope to protect their interests against the might of multinational giants.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

David Freund receives funding from Handelsbanken Research Foundation.

Ulf Holm receives funding from Handelsbanken's Research Foundations.

Stephen R. Buzdugan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.