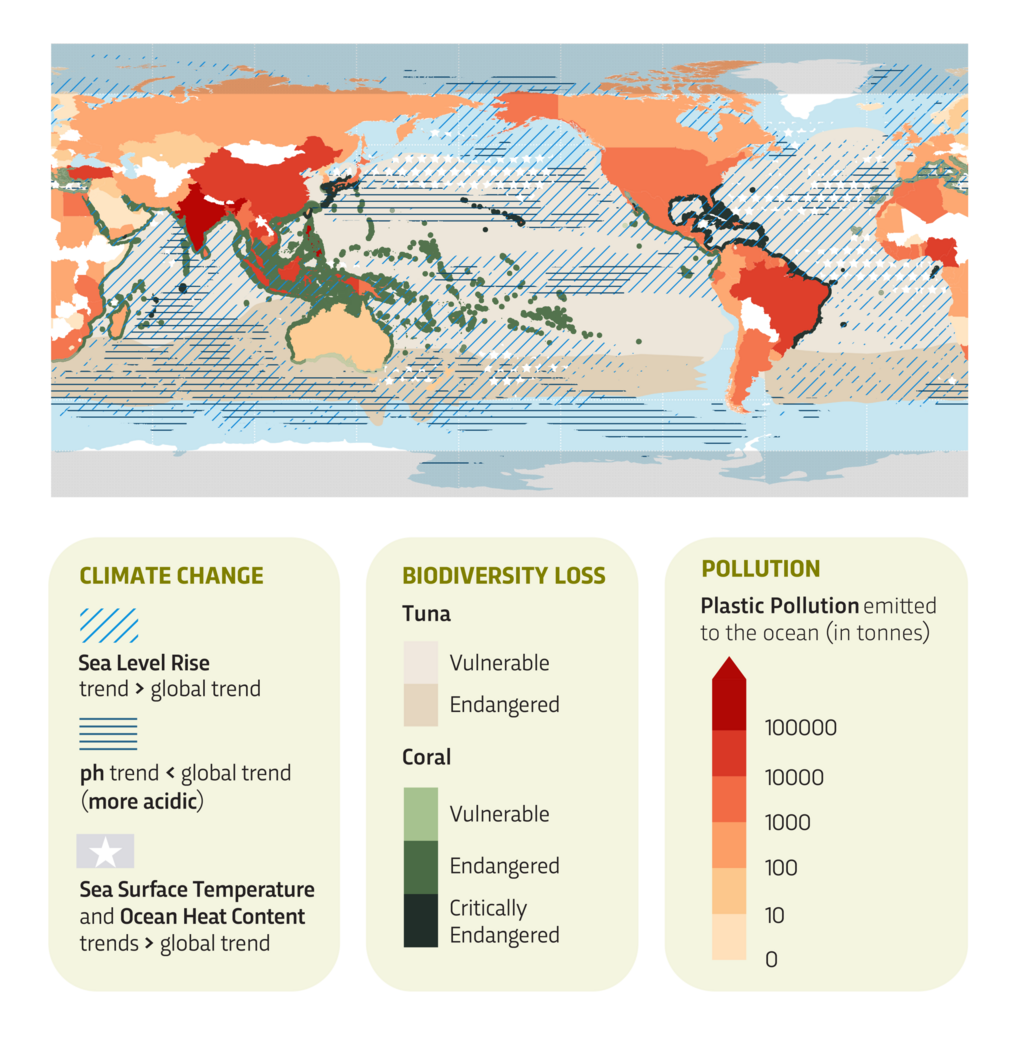

The world's oceans are bearing the brunt of a triple environmental crisis, according to the European Union's Earth monitors: global warming, pollution and declining biodiversity. The EU Copernicus programme warns that Africa's coasts, buffeted by marine heatwaves and rising sea levels, are especially vulnerable.

"The ocean is changing rapidly, with record extremes and worsening impacts," said Karina von Schuckmann, lead author of the programme's latest Ocean State Report, which was released this week.

"This knowledge is not just a warning signal – it is a roadmap for restoring balance between humanity and the ocean."

The world's oceans are facing numerous threats: warming waters, rising sea levels and pollution, all of which are contributing to a decline in marine biodiversity.

Surrounded by oceans on two sides, the African continent is particularly affected, explains Simon van Gennip, an oceanographer at French research centre Mercator Ocean International, which contributed to the Copernicus report.

"Like South America, Africa is exposed to different climatic stressors depending on its western and eastern fronts," he told RFI.

To the north, the Mediterranean is overheating. Between May 2022 and January 2023, surface temperatures rose by up to 4.3 degrees Celsius.

It is experiencing an increase in marine heatwaves – periods of above-average temperatures lasting more than five days in a row.

Stronger, longer heatwaves

In the North Atlantic, which is warming twice as fast as the global average, the waters off Morocco and Mauritania accumulated 300 days of marine heatwaves in 2023.

Mercator counted 250 days of marine heatwaves off the coasts of Senegal and Nigeria.

"We have never seen heatwaves of such intensity, duration and extent," said van Gennip. "There is no part of the North Atlantic that was not affected by a heatwave in 2023. It is truly extraordinary."

The phenomenon continued in 2024 and 2025, he noted, adding that new monitoring tools had allowed scientists to form a clearer picture of warming waters.

"We looked beneath the surface and also observed this phenomenon at depths of 50 and 100 metres," he said.

Warmest oceans in history drive mass bleaching of world's corals

Researchers are still trying to understand the causes. One suggestion is a dip in vast dust clouds from the Sahara, which can help cool the ocean by reflecting the Sun's radiation.

"What worries me most is that these marine heatwave episodes are becoming more and more recurrent, stronger and longer. This trend is unsustainable and there is an urgent need for action," warned van Gennip.

For marine organisms, prolonged thermal stress can lead to problems with growth and reproduction, or even death, he explained.

"Ecosystems are declining or fragmenting as species migrate to more favourable waters. This has consequences for the maritime economy, tourism, fisheries and aquaculture."

Shrinking habitats

Researchers also investigated changing conditions for micronekton – small organisms that are able to swim independently of ocean currents, such as crustaceans, squid and jellyfish.

These species, ranging in size from 2 to 20 centimetres, are an essential link in the food chain. They feed on smaller zooplankton and in turn form prey for larger predators including tuna, marlins and sharks.

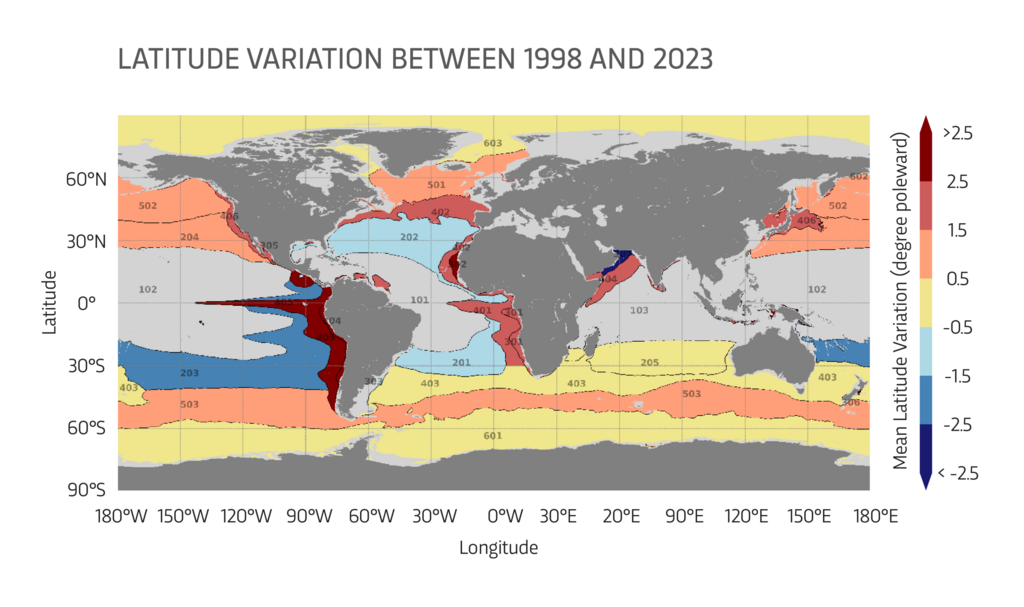

Researchers studied micronekton habitats across the world's oceans, dividing them into "provinces" with comparable temperature patterns and richness in phytoplankton, the microalgae that constitute the first link in the food chain.

French scientists map plankton, the ocean’s mysterious oxygen factories

Like the Pacific coast of South America, the west coast of Africa is rich in phytoplankton because it is subject to "upwelling", the rise of cold water that brings nutrients to the surface.

As water temperatures increase, the concentration of phytoplankton decreases, scientists found. African coasts are among the most affected, along with parts of South America.

"We observed, across all oceans, that the most productive provinces – characterised by significant production of phytoplankton and micronekton, such as upwelling regions – decreased in size between 1998 and 2023," said researcher Sarah Albernhe.

The regions off the coast of Africa decreased by 20 to 25 percent.

Conversely, warmer habitats that are unfavourable to micronekton have expanded over the past 26 years, Albernhe said. Some have increased by more than 25 percent of their initial size.

At the same time, remaining productive zones are moving towards the poles, where cooler waters can still be found.

The province off the coast of Mauritania – which has shrunk by about 20 percent – has shifted about 2.5 degrees northward, or the equivalent of about 300 kilometres.

Carbon exporters

Over time, these trends could lead to "either the relocation of micronekton populations that follow their preferred habitat to new latitudes, or the extinction of species that can no longer find the habitat that suits them", Albernhe warned.

"This will have consequences for the food chains that depend on this phytoplankton, and potentially for the structure of the ecosystem."

Fishing would be affected as boats travel ever further to fish more intensively in smaller areas.

How Europe’s appetite for farmed fish is gutting Gambia's coastal villages

Micronekton is also a powerful carbon pump. It stores at least 15 to 30 percent of the carbon captured by the ocean, making it the largest CO2 sink on the planet.

It helps bury carbon deeper in the ocean as organisms swim from the surface, where they feed on smaller prey at night, down to the depths during the day to hide from predators.

As they descend, they deposit excrement, scales or other carbon-laden parts of themselves. "They are responsible for a very high export of carbon to the depths. They really help us regulate the climate," said Albernhe.

Rising sea levels, acidic oceans

Global warming has also left Africa's coasts buffeted by fast rising waters.

Due to the Earth's rotation, "it's the western edges of the oceans that are generally affected by rising sea levels", explained oceanographer van Gennip.

"In the case of the African continent, it's the east coast of Africa – Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique – that is experiencing a much faster-than-average rise in sea levels.

"The global increase is 3.7mm per year, and in these regions, we see values around 5mm per year."

The acidity level of oceans has also increased by 30 to 40 percent in the past 150 years, according to the Copernicus report.

In Africa, this trend is especially noticeable in the Indian Ocean, particularly the area south of Madagascar and South Africa, van Gennip said. But waters off Morocco and Mauritania are also registering significant declines in pH.

More acidic waters have direct consequences for corals, havens of vital biodiversity: all African reefs, located mainly around Madagascar and as far as South Africa, are in danger or vulnerable.

This article was adapted from the original in French by Géraud Bosman-Delzons.