As climate change intensifies competition over water resources, the River Nile has become a symbol of both development and dispute. RFI speaks to a climate diplomacy expert to understand what’s at stake.

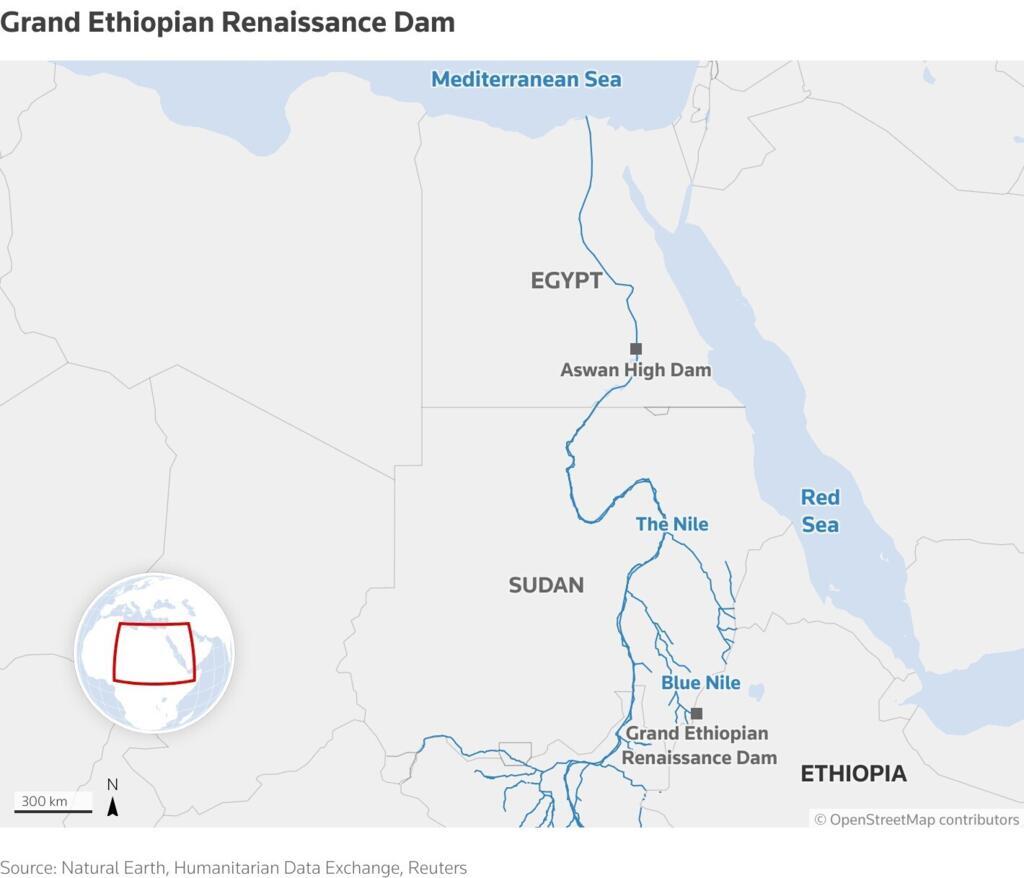

This week, Ethiopia inaugurated the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the River Nile – Africa’s largest hydroelectric project, with an eventual capacity of 5,000 megawatts.

The GERD project promises to transform access to electricity in Ethiopia, and generate export revenues by selling power to neighbouring countries.

But downstream, Sudan and Egypt view the dam as an “existential threat”.

Both rely heavily on the Nile’s waters, and fear the project could jeopardise their supply.

As climate change takes hold, disputes over shared rivers and lakes are expected to multiply. To unpack the issues, RFI spoke with Benjamin Pohl, director of Climate Diplomacy and Security at Adelphi, an international research centre based in Berlin.

Ethiopia inaugurates Africa's biggest dam, despite concerns in Egypt and Sudan

RFI: Who owns the water? It’s a question we hear more and more often, especially when rivers cross borders.

Benjamin Pohl (BP): That’s usually the most controversial point because of competing interests. When a river flows across borders, every country wants to use as much of the water as possible. While cooperation would often mean greater benefits for all, states tend to plan primarily for their own water use – and that often clashes with their neighbours’ plans.

RFI: Is there such a thing as a “right to water”?

BP: International law does cover the use of shared rivers and lakes – notably through the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention and the Helsinki Convention. Neither Ethiopia nor Egypt, though, has signed them.

In essence, international law recognises the right of sovereign states to use shared waters, but only within certain limits.

Usage must be equitable and reasonable, it must not cause significant harm to neighbouring countries, and it should be guided by a general obligation to cooperate.

The problem, however, lies in enforcement. Unlike national legal systems, there is no global authority to police compliance. Instead, everything rests on mutual trust between states or, in extreme cases, intervention by the UN Security Council – a route that is both politically fraught and costly.

Egypt brands Ethiopia's move to fill Nile mega-dam as 'illegal'

'Historic rights'

RFI: Negotiations between Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan have dragged on for decades. What exactly is at stake?

BP: Talks revolve around two things: big-picture rights and very specific risks.

Egypt insists on its “historic rights”, rooted in the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement with Sudan – but that treaty excluded upstream states like Ethiopia. Cairo argues that its entire civilisation has depended on the Nile for millennia, so it has customary rights.

Ethiopia counters that it has sovereign rights to develop and use the water too, pointing out that Egypt has monopolised the Nile for centuries. Addis Ababa stresses that the GERD is for electricity, not irrigation, so water will continue flowing downstream.

Egypt, however, worries about drought scenarios... What if Ethiopia withholds water to maximise power generation? What if the dam were to fail? Or worse, what if water became a political weapon?

Two negotiation tracks are ongoing. One covers the Nile Basin as a whole, though Egypt temporarily walked away before recently returning. The other is a trilateral process between Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan on the Blue Nile – where the GERD is located.

In 2015, they signed a declaration of principles, pledging to cooperate. Since then, technical talks have continued, but a final deal remains elusive.

RFI: What role does climate change play?

BP: Climate change disrupts rainfall patterns and the water cycle. Meanwhile, demand for water is rising fast due to population growth and economic development. In many regions, every drop is already allocated.

Now add climate change: drier conditions mean more irrigation, and hotter temperatures mean more energy use for cooling – which itself requires more water. In short, the pressure is intensifying.

Water crisis driven by climate change threatens global food production

Water diplomacy

RFI: Are there global hotspots where water-sharing tensions are particularly acute?

BP: Absolutely. Over half the world’s rivers cross borders. Conflicts are most likely where political tensions are already high – think North Africa, the Middle East or Central and South Asia.

But here’s the silver lining: most disputes don’t escalate. Political leaders usually find ways to manage them, provided there’s at least some trust and a willingness to cooperate.

RFI: Can shared water management actually improve diplomatic relations?

BP: That’s the dream of every water diplomat! And sometimes, it works.

Take the Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan – it’s survived three wars. Or the cooperation between Brazil and Paraguay over hydropower, and the Senegal River basin initiative in West Africa.

These examples show that shared water can act as a bridge, even between rivals. Still, global water pressure is rising, which makes cooperation ever more essential.

RFI: Looking ahead, what worries you most?

BP: I fear tensions will get worse. But awareness is growing too – there’s nothing inevitable about water scarcity leading to conflict.

What does complicate things is that it’s now easier for countries to build big dams without consulting neighbours. The World Bank used to act as a gatekeeper, ensuring regional consensus. But today, with new sources of finance, even relatively poor countries can push ahead with mega-projects.

That means we’ll see more unilateral infrastructure – and with it, greater potential for clashes. The challenge is to strengthen cooperation so that shared rivers become a source of partnership, not rivalry.

(This interview has been adapted from the original French version and edited for clarity)