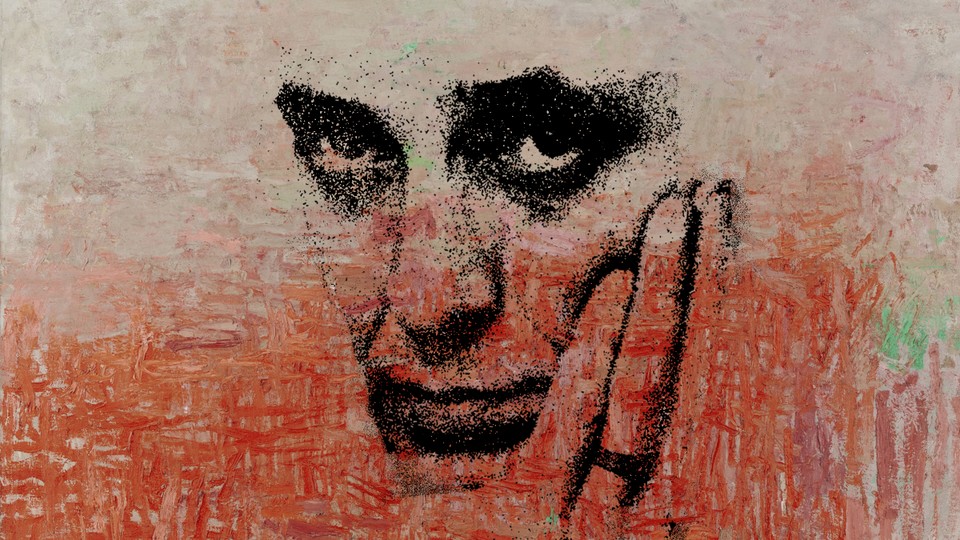

Anybody who has seen one of Philip Guston’s representational paintings knows the rest of them. I mean that in a strictly literal sense: The visual universe that Guston began creating in the late 1960s, when he rejected the abstraction that was then dominating the New York art world, is impossible not to recognize. Guston painted in thick, fleshy pinks, commonly outlining his figures in red or black instead of filling them in. His commitment to this palette was such that, according to his daughter, Musa Mayer, in her memoir Night Studio, when Guston died in 1980, she and her mother inherited “hundreds of tubes of cadmium red medium, mars black, titanium white.”

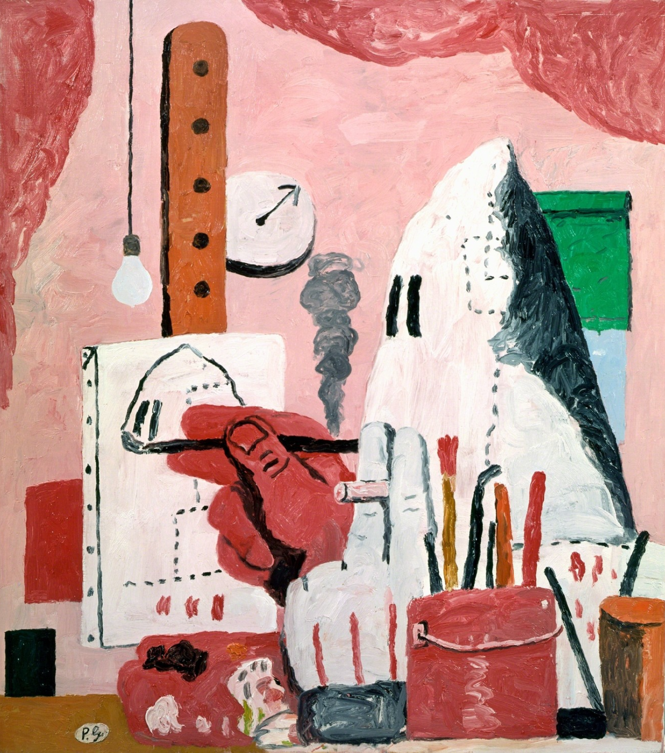

Many of his pink canvases are self-portraits in which he appears as a giant, worried head, all forehead wrinkles and wide eyes; many show household objects—cherries, cigarettes, bottles, light bulbs—swollen to menacing proportions; and many are full of puffy, cartoonish Ku Klux Klansmen, typically doing activities that, per Mayer, came from the routines of their creator’s life: staring down a bottle of alcohol, smoking a cigarette, or, as in the 1969 work The Studio, painting a self-portrait while wearing a hooded white robe.

Guston’s images of Klansmen, which he called “hoods,” are striking in their ability to allow both painter and audience to consider the proximity of evil. But in September 2020, months after the Black Lives Matter protests that followed the killing of George Floyd, four major museums postponed a retrospective of Guston’s work, citing a wish to “reframe our programming.” (The exhibit is now open at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and will travel to three other venues over the next two years.) Plainly, their concern lay with Guston’s Klansmen being misinterpreted or not seen in sufficient context. Many in the art world rebuked the museums for shying away from Guston’s willingness to look racist violence—and his own complicity with it—in the face. Guston put himself in the shoes of the Klansmen he painted to better understand the humans behind the hoods. (He once noted, “What do [Klansmen] do afterwards? Or before? Smoke, drink, sit around their rooms … patrol empty streets; dumb, melancholy, guilty, fearful, remorseful, reassuring one another?”) His paintings, which put bumbling hoods in anodyne settings, render their subjects disturbingly familiar.

In the newly rereleased book Guston in Time, the novelist and critic Ross Feld praised Guston’s capacity and willingness to imbue even “the most upsetting or disquieting imagery” with “a shaggy, even goofy friendliness.” He wasn’t wrong about the friendliness: The hoods look like Hershey’s kisses crossed with Moomins. Yet painting the Klansmen approachably doesn’t defang them. By depicting them so crudely that it can take a moment to identify them, Guston arguably tricked his viewers into lingering—and then urged them not to look away.

Neither Feld nor Mayer engages with this idea at length in their remembrances, but to me, it seems crucial that Guston tackled his hood paintings—which he debuted in a now-famous 1970 show at the Marlborough Gallery—from the vantage point of the white American Jew. Guston’s parents, Leib (later Louis) Goldstein and Rachel Ehrenleib, were Jews who fled anti-Semitism in Odesa, Ukraine. When Guston was a child, the family moved from Montreal to Los Angeles, where the Klan was both visible and powerful. As a young factory worker, Guston participated in a strike that Klansmen helped break. Some of his earliest works were straightforwardly brutal illustrations of the KKK, he recalled in a 1978 lecture; when he exhibited them in the early 1930s, “some members of the Klan walked in, took the paintings off the wall and slashed them.” Guston knew firsthand the effect his art could have; he also knew fear of anti-Semitism, and of the Klan, firsthand.

[Read: The forgotten history of the Western Klan]

Yet by the time he resumed painting Klansmen in the years leading up to his Marlborough show, Guston’s racial position in the United States had shifted significantly. In the 1930s, when he set out to “illustrate, or do pictures of the KKK,” as he said in that lecture, Jews of European descent were rarely considered white. By the 1960s, they more widely were. After the Holocaust, blatant anti-Semitism seemed déclassé. Informal Jewish quotas seemed to vanish from college admissions, and intermarriage became more common.

Interestingly, in a moment that seemed to lend itself to assimilation, Guston turned in the opposite direction. He appeared, at that time, unconcerned about fitting in with any mainstream: He said that he began painting hoods in part as a horrified reaction to police violence at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, which he described as a “trigger” that “pushed me over.” And he began admitting later in life to his shame at having Anglicized his last name from Goldstein in his early 20s, especially given that, per Feld, he still peppered his speech with Yiddish and presented himself as a “doubt-ridden cerebral Jew painter.” He compared his choice to paint Klansmen to the great Jewish writer Isaac Babel’s decision to depict Russia’s Cossacks; Mayer writes in Night Studio that he left abstraction because he felt, as he put it, an urge to “create ‘golems,’” a reference to the animate clay giants of Jewish legend. These reference points reflect the fact that, like his good friend Philip Roth, he was able to succeed as a Jew, not in spite of his Jewishness. Guston could have de-Judaized himself and vanished into whiteness. He made whiteness visible instead.

Although some critics, including the influential Harold Rosenberg, responded positively to Guston’s hood paintings, with their challenging subject matter and clumsy outlines, much of the art world despised and was perplexed by them. (Feld was one of few viewers who reacted positively to the Marlborough show, and he remained an ardent fan.) In the years Guston spent working uneasily in the tradition of abstract expressionism (which Feld calls “one of the most deeply Protestant art-histories ever seen”), he painted in a variety of colors, often focusing on deep explorations of a single hue. When he began painting hoods, he picked up his signature pinks—which are, it seems to me, not just any pink. Guston worked in the streaky, pale-bellied tones of an unhealthy white man’s skin, which is to say of his own. He was a voracious eater, smoker, and drinker who frequently ignored doctors’ advice. In some photographs, his face is the color of his art. Spotting a Guston from across a room is, in a way, spotting the painter’s own variety of whiteness.

Pink evokes girliness, too. Guston’s late-career art overflows with cartoonish femininity, not only in his canvases’ color but in their domestic clutter and swollen curves. Occasionally, this tendency turns sexual—say, in the joyous “gluttony” of the fat red fruits in Cherries (1976), as Feld describes it—but more typically, Guston chooses drab household scenes. Many of his paintings bring viewers into what could be closets or storage rooms. In Flatlands (1970), two hoods stare across a dirty pinkish landscape littered with clocks, old shoes, a book, a basketball. They could be standing in an attic, getting ready to sort through what Feld calls the “crap of life.”

[Read: The art movement that embraced the monstrous]

Feld celebrates Guston’s willingness to paint everyday objects, and to do so in what he implies is—and what I certainly see as—a stereotypically feminine way. Drawing from the theater scholar Jonas Barish, Feld argues that abstract expressionism asked artists to suppress their emotions in favor of creating “Works that testified to inner Faith.” Guston, though, embraced his “histrionic impulse,” imbuing household detritus with dignity and menace, and transforming it into the “ever-present still life that surrounds the embarrassingly, even tragically human.” In Flatlands, Guston’s hoods seem, if not embarrassed, then overwhelmed. They look lost and powerless in their sea of domestic junk—and yet their white robes, even smeared with pale pinks and ashy grays, warn viewers that it would be foolish not to fear them nonetheless.

While visiting the Baltimore Museum of Art’s “Guarding the Art” exhibition in April, I spotted Guston’s 1974 painting The Oracle from a full room away. It’s pink, of course. Half the canvas is littered with shoes heaped in a way that evokes the piles of personal effects found at concentration camps. The big head that tends to stand in for Guston stares at them; a light bulb dangles, closet- or dungeon-style, over his head. Behind him are a pair of hoods, one raising a whip to strike him. My instant interpretation of the painting was that it portrays a habit I recognize from my Jewish family and community: obsessing over the dangers of the past, not turning to look at the present, which is full of threats to Jews and non-Jews alike.

But then I remembered that Guston said he saw himself behind the hoods. (Asked at a talk if the hooded figure could be himself, he said it had occurred to him, adding, “Well, it could be all of us.”) Once I read both the big head and the whip-wielding Klansman as Guston avatars, the painting transformed for me. It remained a portrait of Jewish fear; it also evoked the guilt of an American Jew unable to prevent the horrors of the Holocaust; and it became an acknowledgment of the painter’s own proximity to power and whiteness. Guston’s hood paintings conjure the discomfort and dissonance of this reality. They put viewers in a cramped car or attic not only with evil, but also with unresolved complicity, confusion, and shame.

The novelist Dara Horn has argued that Jewish literature tends to reject neat endings. She considers this inclination a sign of a “realism that comes from humility, from the knowledge that one cannot be true to the human experience while pretending to make sense of the world.” Guston’s hood paintings, perhaps, belong to this baffled tradition. Guston didn’t know what to say about the Klan or about racial violence, except that he knew to fear it as a Jew, and to both oppose and feel implicated in it as a white American. Nearly 50 years after he painted The Oracle, I can’t honestly say I know more.