The EU is moving to regulate artificial intelligence – other countries will follow. Where does that leave New Zealand, and its AI businesses?

Artificial intelligence is amazing. In my tiny business journalist way, I use ChatGPT to help me write headlines, which are not my strong point. Colleagues at BusinessDesk are using the same technology to produce articles from NZX company announcements within 60 seconds of when they are released.

Kiwi farming tech company Halter uses AI-driven technology to move cows, check in on their health, and manage pasture grazing – all remotely. Soul Machines does amazing things with AI and digital humans, including AI-generated duplicate celebrities.

And Rush Digital, another innovative Kiwi business is working with construction company Downer on putting mobile AI camera units on building and roading sites to spot and monitor health and safety risks. It might be someone inadvertently moving too close to dangerous machinery, or not wearing protective gear, or roading machinery accidentally being driven into live traffic lanes.

“This AI-enabled computer vision technology could be applied to all critical risks, enable real-time alerting and live risk assessment, and improve workflows and management through collecting data on site,” says Rush Digital founder and chief technology officer Danu Abeysuriya.

READ MORE: * This election year we need to brace ourselves for AI * Artificial intelligence reviving Māori dialects

But AI is also seriously scary. A new report from the World Economic Forum says because they are easy to use, “generative AI technologies can be open to abuse by people seeking to spread misinformation, facilitate cyber attacks or access sensitive personal data”.

That can be the bad guys on the dark web, but also can be the so-called good guys, the police, for example, or companies using AI in their own products.

“What makes AI a serious risk is its ‘opaque inner workings’,” the report says. “No one fully understands how AI content is created. This increases the risks of inadvertent sharing of personal data and bias in decision making based on AI algorithms.”

Misleading information is a big problem. Take a chatbot, for example, which relies on existing data. But if its datasets have inbuilt bias, or the chatbot misunderstands a question, it can provide someone with information that is basically wrong. But it sounds so convincingly correct, people might well believe and act on it.

Then there are deep fakes. A deepfake uses generative AI to create videos, photos, and voice recordings using the image and likeness of another individual.

In March, hyper-realistic, but totally fictitious pictures of Pope Francis in a high-fashion white puffer jacket went viral. The picture was innocuous enough, created by a construction worker in Chicago who thought it would be funny to use AI to dress the pontiff in a puffer robe.

Still, it created a storm of commentary about the ethical use of artificial intelligence.

“It provided a glimpse into a future where deepfakes create significant reputational, counterfeit, fraud and political risks for individuals, organisations and governments,” said Avivah Litan, vice president analyst at US tech research company Gartner.

Artificial intelligence also raises the spectre of compromised data privacy, violations of copyright and other intellectual property, and making it far easier for hackers to write malicious code and breach an organisation’s cybersecurity, Litan says.

“AI developers must urgently work with policymakers, including new regulatory authorities that may emerge, to establish policies and practices for generative AI oversight and risk management,” she says.

It’s starting to happen. In June, the World Economic Forum published recommendations for the responsible development of AI, which urged developers to be more open and transparent and to use more precise and shared terminology.

Meanwhile, regulation is coming, in China, the US, the UK, Australia and elsewhere. But it’s the EU that has taken the lead on AI, as on other digital regulation, with the first iteration of legislation in the world, as well as the strictest proposed provisions so far.

Last month the European Parliament passed an updated version of the AI Act, strengthened to cover things like ‘generative’ not just traditional (sometimes called ‘weak’ or ‘narrow’) AI.

The step change between them is important when it comes to regulating AI, so here's a quick aside for the uninitiated.

A diversion: generative v narrow AI

Traditional AI does one job really well using a set of inputs – think a chess computer or the Siri voice assistant, or the Google search engine.

Generative AI is the next step in cleverness, in that it can create something new.

Generative AI models are trained on a set of data and learn the underlying patterns. They then use those to ‘generate’ new data that mirrors but does not simply reproduce the training set.

Think the headline suggestions it can produce for my stories, using an outline of the article content. Think the ability to write a student essay, or a screen play. And it’s not just words. Generative AI can produce music, computer code and pictures.

The pope in a puffer.

End of diversion.

This rapid evolution of AI is why the EU has been forced to draw up a revised draft AI Act. The latest version is under discussion with three European bodies – the Parliament, the Council and the Commission – with a final text expected by the end of 2023 or early 2024.

The gist of the EU approach is to define different levels of risks associated with different uses of AI, and set rules around their use.

At the highest risk end for EU legislators is AI used for things like ‘social scoring’ – where a government or a private sector organisation creates risk profiles of individuals based on surveillance of their behaviour, and then penalises low-scoring people. Chinese government surveillance is the example that springs to mind.

Social scoring and other intrusive systems – particularly those involving real-time remote biometric identification techniques – are deemed an “unacceptable risk” to people’s safety, and are banned outright in the EU bill.

The next step down for the EU is when AI is seen to create a "high risk" to health and safety or people’s fundamental rights. "High-risk" systems could involve physical products like AI-assisted machinery, toys or medical devices, or they could be educational or recruitment systems which use AI in a way (scoring, for example) that could determine someone’s future. They might also be border control or law enforcement systems using AI to evaluate information.

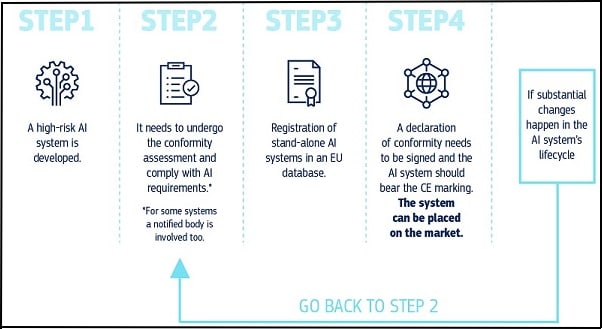

High-risk AI systems will be allowed under the AI Act, but will be subject to a high level of transparency, risk assessment and “human oversight measures”, the European Commission says.

At the end of the EU spectrum are “low” and then “minimal” risk activities, where transparency is required (for low risk) or encouraged (minimal risk).

“The regulatory proposal aims to provide AI developers, deployers and users with clear requirements and obligations regarding specific uses of AI,” the commission says. “The proposed AI regulation ensures that Europeans can trust what AI has to offer. While most AI systems pose limited to no risk and can contribute to solving many societal challenges, certain AI systems create risks that we must address to avoid undesirable outcomes.

“For example, it is often not possible to find out why an AI system has made a decision or prediction and taken a particular action. So, it may become difficult to assess whether someone has been unfairly disadvantaged, such as in a hiring decision or in an application for a public benefit scheme.”

Prescription v principles

Richard Massey is a senior associate at law firm Bell Gully, and has been looking at moves towards AI regulation overseas and how it might impact New Zealand companies.

He says the EU legislation takes what is known as a "prescriptive" approach to AI, as opposed to the more flexible "principles-based" regime proposed, for example, in a recent policy paper from the UK government.

While the EU sets out specific detailed requirements, the UK regime takes what it calls a “common sense, outcomes-orientated approach”.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both.

“The advantage of a more prescriptive system is that it provides a clear a framework within which market participants can build design and implement their programmes. The disadvantage is this technology is moving incredibly quickly, so it might well require quite regular updates and reviews to make sure the regulation can keep pace with the underlying evolutions of the technology," Massey says.

“It feels to me critical that the regulation is set at the right level. And the consequences of unduly stifling innovation and slowing down some of these benefits could be very serious.” – Richard Massey, Bell Gully

Meanwhile, the advantage of a principles-based regime is greater flexibility. "The UK’s white paper is clearly seeking to allow greater innovation. And it avoids that pitfall of having to constantly update itself to make sure it keeps pace with that technology.”

An Australian consultation paper on AI is still at an early stage, but Massey says indications are “for that slightly more detailed, prescriptive approach, closer to what we’ve seen in the EU”.

The impact in NZ

The New Zealand Government hasn’t yet come out with any thoughts around legislating AI, although the Office of the Privacy Commissioner is running a consultation into the use of biometric technology and whether that needs a code of practice under the Privacy Act.

Massey says holding off on taking a position until other countries have tested the waters seems like a good approach for New Zealand.

The EU’s competition chief Margrethe Vestager told the BBC "guardrails" were needed to counter the biggest risks around AI technology and there was a need to get rules in place sooner rather than later, even if that meant pressing ahead with legislation that was only 80 percent right.

“That inherently implies there are shortcomings in the draft law but the interest of expediency outweighs perfection in the drafting,” Massey says. “I don't know whether I entirely agree with that, given the significant benefits that technology can offer.

“It feels to me critical that the regulation is set at the right level. And the consequences of unduly stifling innovation and slowing down some of these benefits could be very serious.”

New Zealand companies are doing a range of interesting things in AI and there could be potential in the climate change, agricultural, healthcare, consumer products and other sectors, Massey says.

“There are a whole range of really exciting potential use cases that can be unlocked through appropriately-regulated AI. And the key is to ensure that it's not over-regulated in a way that loses some of its benefits or defers those benefits unnecessarily. It's a difficult balance for governments to get right and at the moment no one's got the right answer.

“In one sense it's an advantageous position for New Zealand to be able to look at these existing approaches and consider what works and what doesn't.”

Still, New Zealand companies working with AI and targeting customers in Europe need to be looking carefully at the EU legislation and how it might impact them, Massey says.

“There are potential use cases which could be caught by the AI Act, so it’s worthwhile for businesses engaging in those sorts of activities to think carefully about the possible implications if the act was finalised in its current form.

“It might also help steer the design of some of these technologies to ensure that where any development work is at an early stage it can be achieved in a way that falls within the lower-risk categories, and avoids, in particular, the unacceptable risk categories.”