It can be hard work being a Wes Anderson fan. When someone hates him, they tend to do so relentlessly. The accusations remain the same: his films are too twee, too stiff, too symmetrical. There are too many vinyl records and leather suitcases, too many precocious brats, and too much Bill Murray. In short, they’re too much of the perfect, coordinated same.

But to a true-blue Andersonite, that’s like standing on the deck of a boat, looking down at the ocean’s surface and declaring it devoid of life. His films are beautifully regimented, yes. Beyond that, they’re also pulsing with thought and emotion, drawn to every corner of the globe, from Hans Holbein the Younger to filmmaker Satyajit Ray, and powered by history and personal remembrance. He captures what it’s like to feel adrift in your own family, to feel hollowed out by grief, or to cling to the fragile dream of solidarity in the face of fascism.

So, as Anderson unveils his latest film The Phoenician Scheme, I’ve ranked all 13 of his released features, from worst to best. Each has something to offer us.

13. Isle of Dogs (2018)

Anderson’s second stop-motion film is the neglected sibling to The Grand Budapest Hotel. At the heart of both is the idea that fascism, in its need for control, obliterates all that is worthy about humanity. Here, in retro-futuristic Japan, all dogs are banished to Trash Island and, with them, companionship itself. Where it stumbles is Anderson’s controversial choice to leave the film’s Japanese dialogue unsubtitled, so that its English speakers, namely Greta Gerwig’s freckled exchange student, were essentially handed control of the narrative. Others weren’t so keen on all the anti-cat sentiment.

12. The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Three More (2024)

Netflix played a duplicitous hand when it first released Anderson’s quartet of Roald Dahl shorts as separate instalments, only to stitch them together as a feature after the filmmaker received his Academy Award for Best Live Action Short. Still, it was his first Oscar, and long overdue. And while the anthology may seem comparatively slight, it’s an important chapter in the director’s ever-escalating obsession with artifice. Here, visible stagehands move props and sliding walls, while a small troupe of actors, including Benedict Cumberbatch, feature in rotating roles.

11. Bottle Rocket (1996)

Columbia Pictures wasn’t quite prepared for what the young, well-mannered Texan in the college professor threads would deliver when they handed him $5m to make his feature debut. What they wanted was a sardonic crime caper to cash in on the Tarantino craze. What they got was far sweeter – not as formally ambitious as the rest of Anderson’s oeuvre, but driven by the same naïve malaise that infects the rest of his characters, as Dignan (co-writer Owen Wilson) turns to crime to advance his 75-year plan for his future. It failed at the box office, but gained an instant fan in Martin Scorsese.

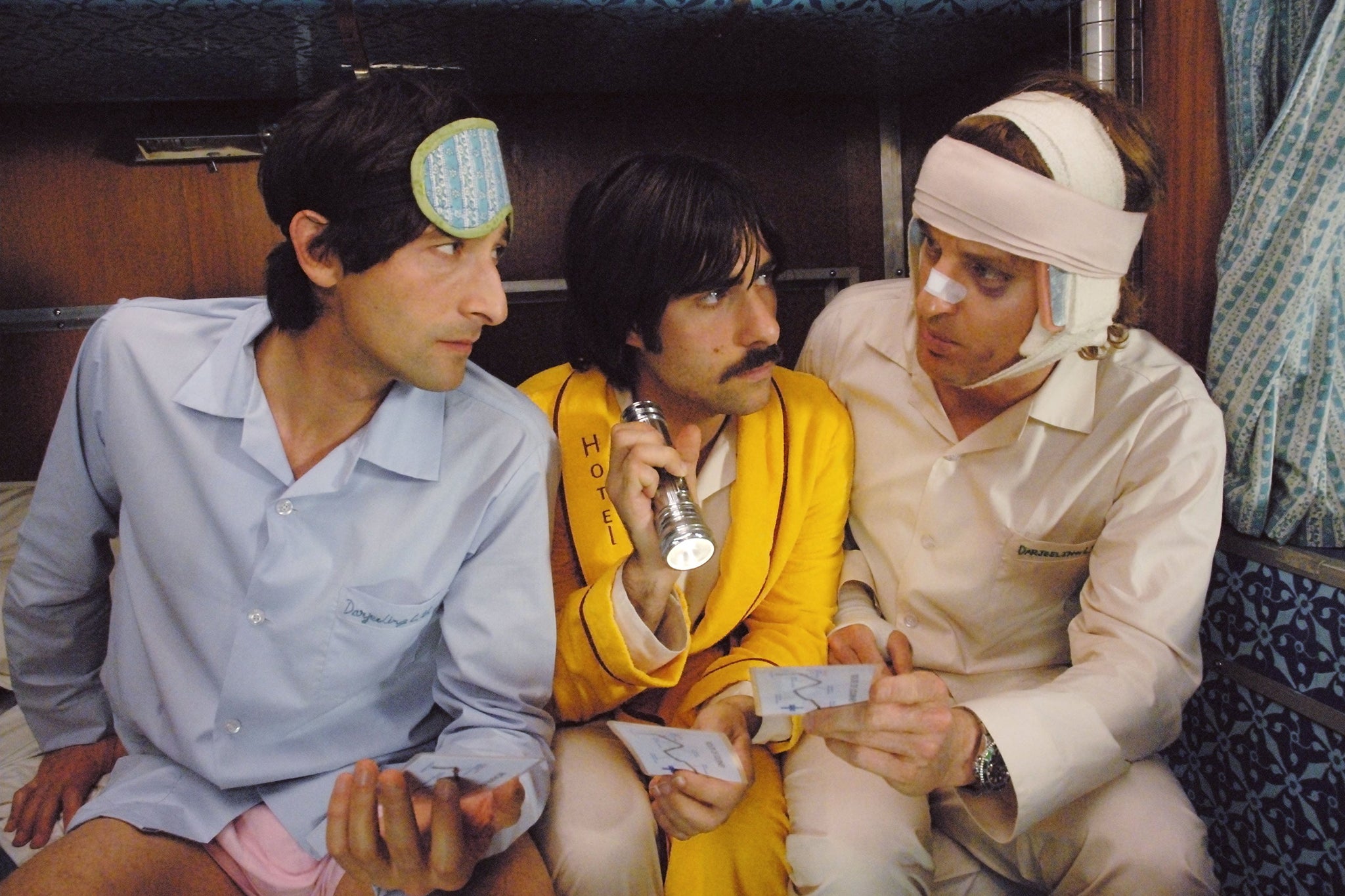

10. The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

The Darjeeling Limited is as spontaneous as Anderson gets. Frustrated by the high-profile failure of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, the filmmaker shrank his budget and crew down to a minimum, refitting a real, broad-gauge train to film in as it travelled across the Indian countryside. It forms the central stage for his tale of three brothers (played by Jason Schwartzman, Owen Wilson, and Adrien Brody), who make a last-ditch effort to heal what’s broken. But Anderson struggles, in places, to warn against his protagonists’ fetishisation of Eastern spirituality without falling prey to those tropes himself.

9. The French Dispatch (2021)

Considering Anderson’s been a part-time Parisian since 2005, it was inevitable he’d make something substantial out of his fervent Francophilia. Yet the result, an anthology picture that brings to life the final issue of a fictional, New Yorker-inspired magazine, isn’t strictly a film about France, but about what it means to observe, both as a writer and a foreigner. Those who dismiss it as too precious seem to overlook the ambivalent endings to his short stories: we see art and protest commodified, and artists unsure about the worthiness of their own isolation.

8. The Phoenician Scheme (2025)

The Phoenician Scheme is Anderson’s angriest film yet. No one rants or raves – it’s altogether more polite than that – but its story of a wealthy industrialist (Benicio del Toro) who appoints his sole daughter, a nun (Mia Threapleton), as his heir, is bookended by exploding bodies. There’s all sorts of violence within, of the physical, emotional, and moral kind, though the dreamer in Anderson wonders at exactly what it would take to save the soul of the indefensible. Call it his way of processing the modern state of our world.

7. Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

Few films understand the child’s world as innately as Moonrise Kingdom. Anderson knelt to their level, shooting on cameras held at chest-level, requiring their operators to look down through a lens at their top. He found emotionally intelligent leads in Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward. And, in his tale of runaways on the fictional island of New Penzance, he treated his young heroes’ disaffection with as much respect as he did his adult characters, among them a disarmingly introverted Bruce Willis.

6. Fantastic Mr Fox (2009)

Here’s the Wes Anderson film to show someone who’s never seen a Wes Anderson film before. It’s an autumn-paletted, charmingly hand-crafted tale of stop-motion foxes wreaking havoc on a trio of farmers, with a madcap silliness that’s easy on the eyes and heart (the whole thing ends with a boogie in a supermarket to The Bobby Fuller Four). Still, the expansions Anderson made to Roald Dahl’s relatively slim text allow it to emerge as a sophisticated parable about the need for community over individual social advancement.

5. The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004)

It’s the closest Anderson’s ever come to career disaster, coming in at $8m over budget and then falling flat at the box office. Yet The Life Aquatic remains the most unfairly maligned of Anderson’s films. Accusations of whimsical self-satisfaction fail to hold up against its elementally moving climax, in which washed-up oceanographer Steve Zissou (Bill Murray, in a career-best turn) comes face-to-face with the shark that killed his friend, the living totem of cruel fate, and decides to let it swim away.

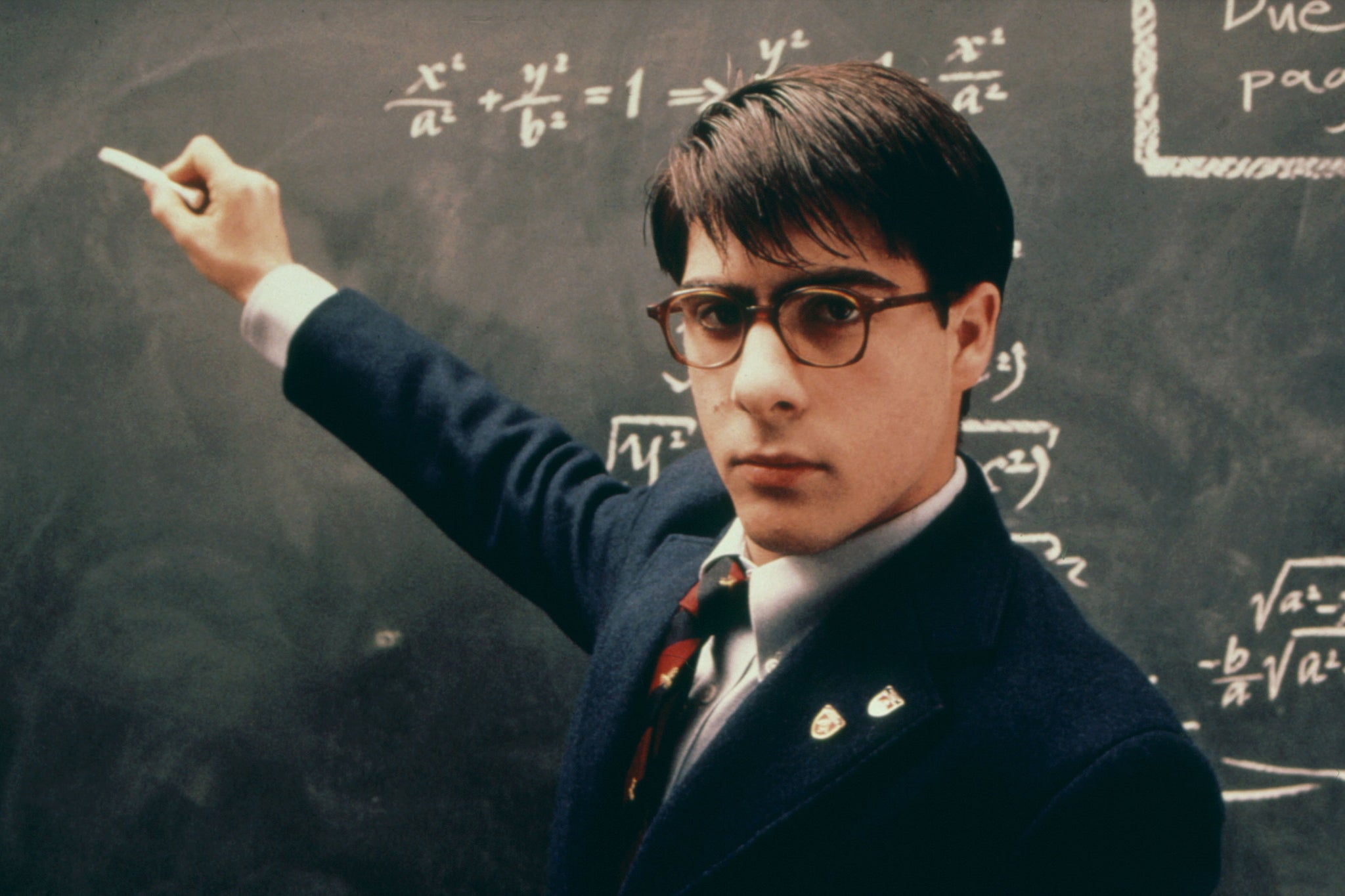

4. Rushmore (1998)

Anderson’s second film, and his first to feel quintessentially Andersonian, introduced many of his key obsessions: visualised lists of objects and accomplishments, framing devices (the film is presented to us from behind red curtains, as if it were a stage play), and his twin muses, Bill Murray and Jason Schwartzman. It also argues most beautifully for what Frances McDormand’s character in The French Dispatch calls “the touching narcissism of the young”. Student Max Fischer (Schwartzman), delusional in his academic success and in his infatuation with his teacher (Olivia Williams), proves oddly lovable in his resilience. At least somebody’s fighting for the Latin language.

3. Asteroid City (2023)

It might seem blasphemous to put a more recent Anderson above a classic like Rushmore, but Asteroid City has a cumulative weight to it. It’s everything Anderson has explored so far and more – an intricate construction of a television special about a stage play about an alien visitation to an American desert town, that aligns the act of artistic creation with the thrill and uncertainty of space exploration. “I still don’t understand the play,” an actor (Jason Schwartzman) confesses, only for his director (Adrien Brody) to offer the advice: “Doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story.”

2. The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

The Grand Budapest Hotel isn’t a direct adaptation of Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday, sent to his publisher the day before he took a fatal dose of barbiturates. But it does capture its profound sense of sorrow, as the author watched his once-promising haven in the Viennese coffee houses, alive with fertile ideas and wondrous art, fall to the inhumanity of Hitler’s regime. Yes, Ralph Fiennes lands every moment of slapstick absurdity in what is, essentially, a caper film set in a fictional European nation. But Anderson’s biggest hit (both at the box office and the Oscars, where it won four awards), owes much to the grief we see in the actor’s eyes, as concierge M Gustave realises he’s living through the last days of civility.

1. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

Every Wes Anderson film is, at its core, about how there’s no glory in a one-man island, whether we’re talking nations, communities, or families. And no character learns that lesson in a sharper, funnier, more affecting way than Gene Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum. He tries to con his way back into the life of the family he abandoned, of his scholarly wife (Anjelica Huston) and three former prodigy children (Luke Wilson, Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Stiller), and expects all to be forgiven.

Hackman’s performance, reluctantly secured (he turned Anderson down multiple times before relenting), was his third-to-last before retirement. But it’s one of his greatest, specifically because it dances with and pushes against the brusque and authoritative characters of his past, in The French Connection or The Conversation. He’s the ultimate Anderson character: a man convinced he’s one thing – a renegade – who learns that he’s something a lot more flawed and vulnerable – a father – instead. Anderson, for all his highly coiffed worlds, loves to force his characters to face reality. He’s always done it well, but never better than here.

Inside the obsessive, compulsive making of a Wes Anderson set

Wes Anderson isn’t in a rut, but he could do with another flop

Spike Lee says ‘people are hurting’ in jab at Trump’s foreign-made film tariffs

Inside the secret world of Pee-wee Herman – and the man behind him

Matthew Rhys: ‘I’d have played James Bond as a Welshman until they told me to stop’

Cinema’s latest trend? The frustrated descendants of the American western