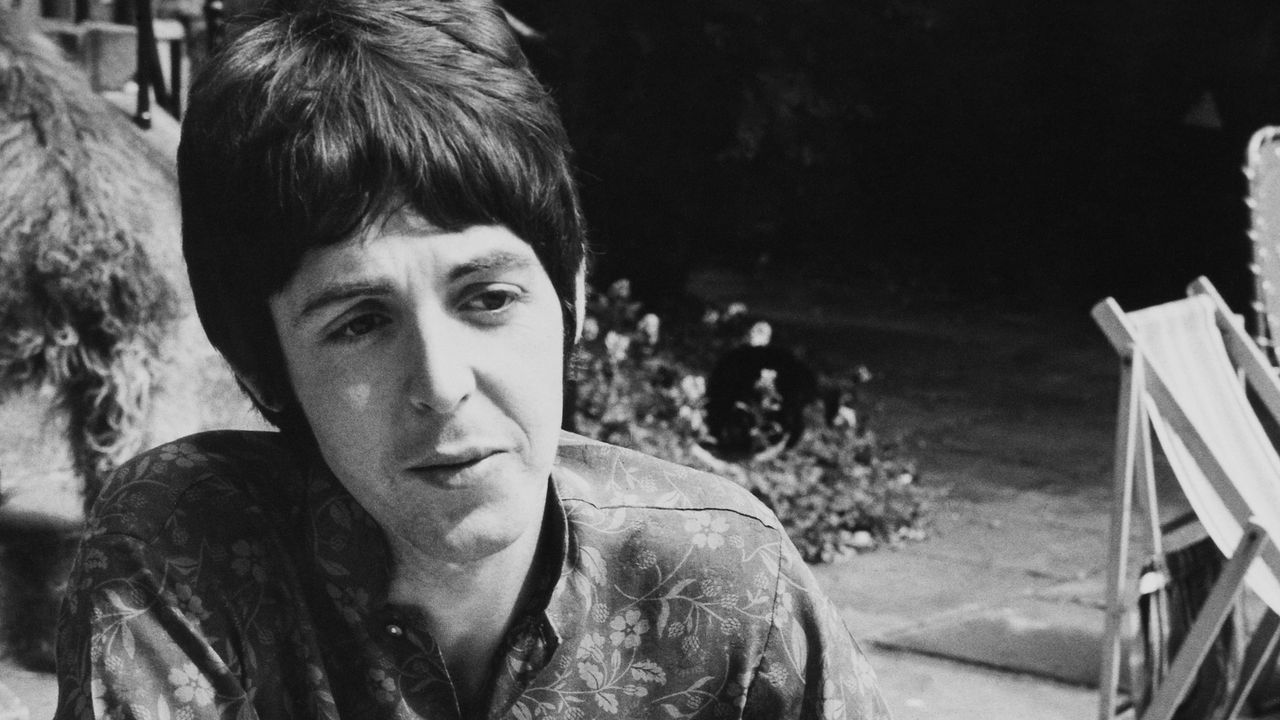

Paul McCartney has been talking about how exposure to avant-garde music enhanced the Beatles in the late '60s and coloured some of their greatest work.

Macca has been interviewed by Radio 3 presenter Elizabeth Alker for her upcoming book Everything We Do Is Music, which explores the links between pop and classical music. In a piece in the Guardian, Alker describes meeting the ex-Beatle in his office as he remembers how he educated himself about experimental music.

McCartney saw experimental composer Cornelius Cardew in concert, attended a lecture by Karlheinz Stockhausen about synthesised music and met Delia Derbyshire. By 1966 all this background work was flowing into the Beatles' music.

The first track to benefit from this new type of thinking was Tomorrow Never Knows, for which McCartney set up a couple of Brenell tape machines to create loops. “I set up the tape machines to create popping, whirring and dissolving sounds all mixed together.

"There could have been a guitar solo in it – straightforward or wacky – but when you put the tape loops in, they take it to another place because when they play, you get all these kind of happy accidents. They’re unpredictable and that suited that track. We used those tricks to get the effect we wanted.”

The following year brought I Am The Walrus, which in many ways went even further out. “(John) Cage had a piece that started at one end of the radio’s range,” he says, “and he just turned the knob and went through to the end, scrolling randomly through all the stations.

"I brought that idea to I Am the Walrus. I said, ‘It’s got to be random.’ We ended up landing on some Shakespeare – King Lear. It was lovely having that spoken word at that moment. And that came from Cage.”

Interestingly, McCartney said he wanted to use this new technology “in a controlled way”, still working within the limits of a three-minute pop song.

When the less cautious Lennon got his hands on a pair of Brenell machines, the result was Revolution 9, the extraordinary cut-up piece that must have astonished (and terrified) the group’s audience when they heard it for the first time on the White Album in late 1968.

But by bringing these elements into pop music, both Beatles were gently pushing their audience – and thus popular culture – forward. “You think, ‘Oh well, our audience wants a pop song,’” McCartney says.

“And then you might read about William Burroughs using the cut-up technique and you think, ‘Well, he had an audience, and his audience liked what he did.’ And eventually we decided that our audiences would come along with us, rather than it being down to us to feed them a conventional diet.”

Anyway, Alker’s book Everything We Do Is Music sounds fascinating. It’s out via Faber & Faber on August 28.