Beneath the epic tales of heroes and gods, Troy’s true story is written in something far less glamorous – its rubbish.

When we think of Troy, we imagine epic battles, valiant deeds, cunning tricks and the wrath of gods. Thanks to Homer’s Iliad, the city is remembered as a stage for romance and heroism.

But long before Paris stole Helen and Achilles raged on the battlefield, the people of bronze age Troy lived ordinary lives – with extraordinary consequences. They built, cooked, stored, traded and, crucially, threw things away. And they did it right where they lived.

Today, waste is whisked away quickly – out of sight, out of mind. But in bronze age Troy (3000–1000BC), trash stayed close, often accumulating in domestic dumping grounds for generations.

Having spent more than 16 summers excavating and analysing the bronze age layers of Troy, I’ve learned to read the city’s history this waste.

Hundreds of thousands of animal bones from cattle, sheep, fish – even turtles – were found alongside vast quantities of pottery shards, ash, food scraps, and human waste. Sometimes, these layers were reused to level floors or build walls, showing how closely intertwined daily life and refuse management were.

Archaeology’s dirty secret

This wasn’t laziness or neglect, it was pure pragmatism. In a world without rubbish trucks or sanitation systems, managing refuse was neither chaotic nor careless, but a collective, spatially negotiated – and surprisingly strategic – effort.

The excavations I have worked on as part of the University of Tübingen’s Troy Project, which has been going on since 1988, have revealed just how deliberate these routines were. Where people chose to dump, or not to dump, speaks volumes about status, social roles, and community boundaries. Waste is the diary no one meant to write, yet it records the intimate rhythms of daily life with unfiltered clarity.

Far from a nuisance, Troy’s waste is an archaeologist’s treasure trove.

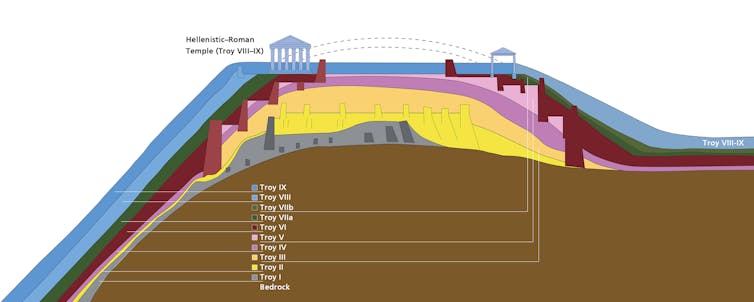

Over nearly 2,000 years, Troy ended up with 15 meters of built-up debris. Archaeologists can see nine major building phases in it, each made up of hundreds of thin layers, which formed as people lived their everyday lives. These layers act like snapshots, quietly recording how the city changed over time. Some capture hearth cleanings, others record the rebuilding of entire city quarters.

By analysing the layers and their ratios of bones to pottery, ash concentration, presence of storage jars, grinding stones, or production debris, specific spaces of activity become visible: kitchens, workshops, storage areas, rubbish pits. What appears chaotic turns out to be a carefully structured map of everyday routines – showing where meals were prepared, tools made, and discarded objects left behind.

The story these remains tell is one of profound transformation. Troy began as a modest agrarian settlement, shaped by the steady rhythms of farming, herding, and small-scale craft. Over time, it grew into a thriving regional centre.

The archaeological record, rich in refuse, traces this long arc of change. Exotic imports fashioned from stones such as carnelian and lapis lazuli begin to appear, revealing distant trade connections. Specialised metalworking tools emerge alongside monumental architecture. some buildings stretched nearly 30 metres, signalling growing ambitions and expanding capabilities.

This rise unfolded gradually, reflected not just in grander buildings, but in shifting tools, trade, and how people dealt with what they left behind. Waste management became more organised, with designated areas for different types of waste. This reflects broader shifts in how the community structured space and managed its economy.

Yet this ascent was interrupted. By the mid-third millennium BC, signs that things were becoming smaller appear. Architecture simplifies, household inventories shrink, production debris declines suggesting economic slowdown or political instability.

Still, Troy endured. By the mid-second millennium BC, the city revived. Refined ceramics, luxury imports and evidence of social complexity marked a new chapter of recovery and reinvention. This splendid settlement later became the stage for Homer’s Trojan War where Greek warriors faced the daunting task of climbing towering mounds of debris built up over centuries just to reach the palaces.

A heap worth climbing

These insights allow us to see Troy not just as a city of walls and towers, but as a living organism shaped by daily routines, unspoken norms and social negotiation. The waste left behind is a remarkably honest archive of bronze age society – beneath myths, stones, and poetry.

Troy’s trash heaps are the bronze age’s search history. To know what mattered 4,500 years ago, don’t ask poets – ask the garbage. From broken tools to shared meals, from imported luxuries to scraps, this waste reveals the pulse of everyday life and society’s evolving structure.

Ironically, these mundane refuse layers preserved the bronze age world for us. Without them, we’d know far less about early Troy’s people. Their depth and composition trace changes in economy, technology, and social structure. From scraps to towers of pottery shards, waste archaeology is key to understanding early urban complexity.

So next time you picture Achilles storming Troy’s gates, remember: the heroes might have been divine, but their city smelled very human.

Stephan Blum does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.