KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Standing at the corner of 22nd and Brooklyn today, you overlook a site where the Sultan of Swat, Babe Ruth, played (exhibitions in 1927 and 1931) and the Sultan of Sod, George Toma, made his name.

You gaze at the scene where the Dallas Texans morphed into the Kansas City Chiefs in 1963 ... and from where they were propelled to two of the first four Super Bowls and played in what remains the longest game in NFL history (double overtime, 82 minutes 40 seconds) in their finale at the stadium built in 1923.

In the distance before you is where soccer legend Pele played in a 1968 exhibition and the Spurs launched an NASL championship in 1969.

It's where they held the 1960 MLB All-Star Game and where The Beatles played in 1964, opening with a "Kansas City/Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey" medley. And it's where the man who made that happen, Kansas City Athletics' owner Charlie O. Finley, contrived a petting zoo in the outfield.

It's also where, after Finley took his A's (and future Hall of Famers Reggie Jackson and Catfish Hunter) to Oakland following the 1967 season, the Royals debuted in 1969 and played in the final event held there 50 years ago this October.

This was the stage for numerous future New York Yankees stars, including Mickey Mantle and Phil Rizzuto, playing for what had become a key minor-league affiliate, the Kansas City Blues.

And it was the location of the last game played by baseball icon Lou Gehrig, who after an exhibition here in 1939 took a train from Union Station to Minnesota and the Mayo Clinic — where he was diagnosed with ALS.

For all this, though, the most enduring and culturally pivotal history hovering on the former grounds of Municipal Stadium (among other names over time) is its vital place as the hub of the Negro Leagues.

In the city where the Negro Leagues themselves were founded, and where the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum keeps the profound tale vibrant and resonant, a galaxy of stars whose story is entwined with the fight for civil rights played for and against the Kansas City Monarchs.

More players went on to the major leagues (which only recently have acknowledged the Negro Leagues as, in fact, major league) from Kansas City than any other franchise, a path blazed 75 years ago this April by former Monarch Jackie Robinson.

That explains why the near foreground of the area came to be dedicated 10 years ago as "Monarch Plaza, Historic Site of Municipal Stadium," intended to celebrate the history framed by the Monarch Manor housing development that now occupies most of the ground.

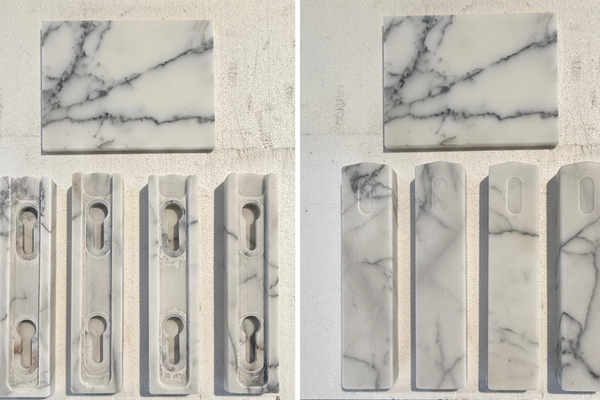

So it's a jarring shame how the main display and kiosks commemorating the rich past and honoring Black athletes (including former Chiefs Willie Lanier and Bobby Bell) have been neglected and weather-ravaged.

Enough so that even their names have been washed away, and, as NLBM president Bob Kendrick put it, "their images started to fade."

But the reassuring news is that it's on the verge of being reinvigorated, in more ways than one, in the wake of a stark moment last summer at the site about a mile from the NLBM.

As Kendrick filmed a segment on the scene for Toyota's "History Hits The Road" series, NLBM community engagement and digital strategy manager Kiona Sinks gazed around her.

Afterward, she simply said, "Bob, I think we need to kind of figure out a way to make this area nicer."

Further prompted by a friend of the museum tweeting about the issue, Kendrick deputized Sinks to explore and spearhead a way to "breathe life back into it," as she put it.

Safe to say the resuscitation is well underway.

With Sinks engaging the city, DRAW architecture and the Missouri Department of Conservation in the cause, plans are in place to have a new display ready for a ceremony on May 6 — the date Robinson played his first professional game here in 1945 as the gateway to being signed by the Dodgers later that year.

Most of the elements are in development or remain to be revealed, and funding is still being worked out both for the immediate and the future.

But Robinson will be a focal aspect of the new look.

And so will what might be called, well, cross-pollination:

Wendy Sangster, community conservation planner with the Missouri Department of Conversation, sees in this a chance to beautify an underrepresented part of the city and call attention to the plight of the monarch butterfly.

"They've declined at an alarming rate in the last 20 years," said Sangster, who was struck by the idea of "Monarchs and monarchs: Somehow we've got to make this work."

She added, "It's not just that they're pretty. We depend on them."

So what better way to further promote monarch waystations to help their reproduction, sustain their migration and crucial role in nature's cycle than by planting pollinators at a site in their very name?

Which will help the plaza transform to a butterfly from this caterpillar phase. And thus restore the vision of Stuart Bullington, who in 2012 ran the city's housing and community development division, that was carried out by then-city development specialist Shawn Hughes

"I would hope it gets refurbished, because future generations need to be aware of what once stood there and what it represented," Hughes said. "Not only to the community but to the city as a whole."

This time, with a deeper understanding by all that a clear plan for its future care is fundamental.

"We're all working diligently to figure out a game plan to not only redo it but maintain it," Kendrick said. "If we're having this same conversation two or three years (from now), then we've all done it a disservice."

As ever with the creative minds at the NLBM, there's also a belief that this one concept can morph into something more in the name of the Monarchs (the name also adopted now by the former Kansas City T-Bones of the American Association).

Kendrick has long contemplated the possibility of a Black baseball tour. One that could go by the site of the stadium built in 1923 and perhaps include visits to Buck O'Neil and Satchel Paige's homes and their grave sites at Forest Hills Cemetery and the Paseo YMCA, where the Negro Leagues were founded, and end at the museum.

More immediately, he said, the NLBM is "tinkering with the notion" of a March of the Monarchs on May 7 as a way to give the 1942 Negro Leagues World Series champions what he called "the parade they never had."

The idea would be a sort of reverse of the tradition of a marching band leading Monarchs fans from 18th and Vine to 22nd and Brooklyn on opening day and other special occasions.

In this case, the call would go out for fans to don their Monarchs gear and make the walk to the museum from a Monarch Plaza freshly befitting its heritage.

"If something's going to bear the name of the Kansas City Monarchs in this community," Sinks said, "it needs to look the part."

And 50 years after the stadium closed and 75 years after Robinson went on from here to break the color barrier, Kendrick added, "This is as appropriate a time as any."

To reanimate all that happened there.

And, most of all, reiterate the meaning of the Monarch name here.