This article first appeared on our partner site, Independent Persian

Two months ago, Iran was reeling from unexpected and intense Israeli attacks. Israel struck selective targets across Iran’s vast geography with two main goals: first, to cripple and suspend Iran’s advanced nuclear program; and second, to assassinate senior Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commanders and top nuclear officials and scientists.

Within 48 hours, several high-ranking IRGC commanders were killed in targeted strikes, plunging the country into its most serious crisis since the Iran-Iraq war began 45 years ago as Independent Persian reported.

During those 12 days of fighting, ordinary citizens were also among the victims of Israel’s precision attacks. But what was striking was that public anger in Iran leaned far more heavily against the Islamic Republic than against Israel. The depth of resentment toward the regime outweighed any outrage at the foreign aggressor.

Runaway inflation, a bleak outlook for the younger generation, mass emigration to uncertain futures abroad, poverty and entrenched corruption – these are only some of the reasons so many Iranians have turned against their rulers.

As the war dragged on and Iranians grappled with fear and trauma about what the conflict might mean for their future, the regime further alienated them by seizing the bodies of those killed in Israeli attacks.

The most basic right of a grieving family is to choose where their loved ones are buried. Yet the Islamic Republic denied them this too. The victims of Israel’s attacks were all buried in the “martyrs’ sections” of their local cemeteries, regardless of the families’ wishes.

Decades of inhumane and immoral conduct by Iran’s security establishment have left the public asking with resentment: Why did Israel stop its attacks? And when will a new war begin to bring down this regime?

Such shocking questions and unprecedented wishes are rare in history. For a people to openly long for foreign strikes to kill their own rulers and topple their regime – at any cost – reveals the depth of despair and helplessness created by nearly half a century of imposed hardship.

The expression “at the end of one’s rope” captures the reality faced by Iranians today. After enduring the psychological toll of Israel’s assault and Iran’s retaliatory missile strikes, their patience has finally snapped under the weight of constant water and power outages at home.

Now, as European signatories of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal consider triggering the “snapback mechanism” – a move that would reinstate previous UN sanctions on Tehran – speculation is mounting over the possibility of another war.

Iranian officials have warned that if the snapback is activated, the country will withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Such a move would provide Israel with renewed justification to claim Iran is pursuing a nuclear weapon, potentially igniting another round of strikes – this time with the backing of the Western signatories of the 2015 deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

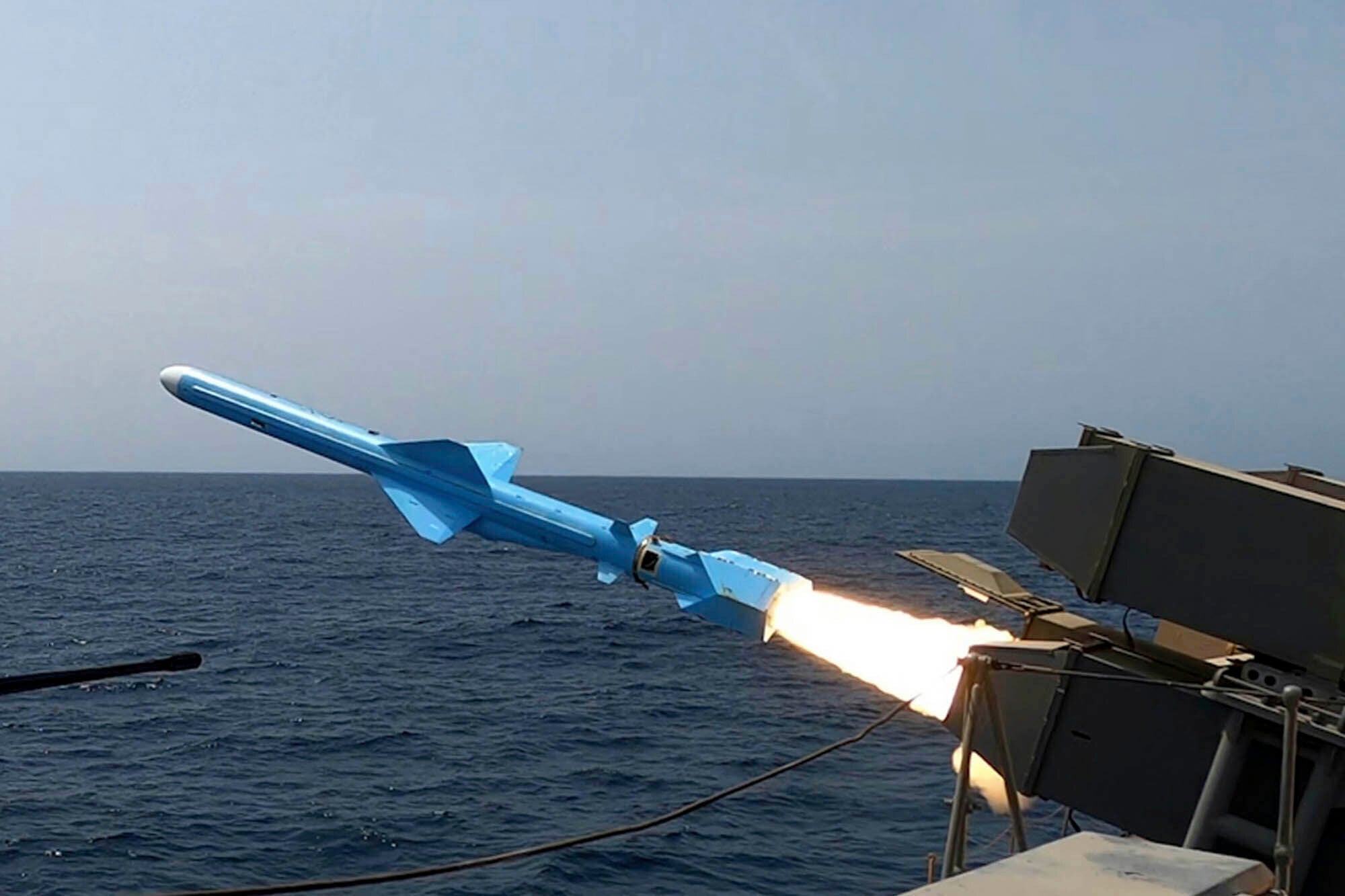

As threats escalate and events move quickly, Iran’s military and political leadership have said they will use new missiles to strike Israel in the event of any attack. Some have even suggested the IRGC might launch pre-emptive strikes.

Yahya Rahim Safavi, a senior advisor to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and a former IRGC commander, spoke openly about the risk of renewed conflict, saying: “We are not in a ceasefire, we are in a state of war. This can collapse at any moment, since there is no protocol, agreement or treaty between us and the United States or Israel. I believe another war may erupt. And the best defence is offence.”

Europe has until the end of August to decide whether to trigger the snapback clause. Under the JCPOA, all parties were granted the right to unilaterally reimpose sanctions or even scrap the agreement if the other side was found in violation. Activating this clause would nullify UN Resolution 2231 and reinstate earlier Security Council resolutions – including 1696 and 1929 among others – that were passed between 2006 and 2010 to penalise Iran over its nuclear program.

A simultaneous withdrawal from the NPT and reimposition of sanctions could also expose Iran to measures under Chapter VII of the UN Charter – the provision that allows military force in response to threats to global security.

Meanwhile, the consular sections of Western embassies in Tehran remain closed two months after the 12-day war, and failed diplomacy with Western powers and the US have left ordinary Iranians in limbo.

Arab states in the region are eagerly awaiting the 80th UN General Assembly in September. They are intensifying efforts to secure recognition of a Palestinian state, which they see as the first step toward independence and peace. Another Iran-Israel war would derail those efforts and bring unpredictable fallout across the entire region.

There is also the possibility that Western governments might delay activating snapback for a limited time, to better assess the risks of a potential conflict.

Iranian officials insist they are fully prepared to respond to any threat or attack. Whether these declarations serve as an effective deterrence or merely as a reassurance to a weary and disillusioned population remains an open question.

And the most pressing question remains: if war breaks out again, what targets will Israel and the United States pursue this time? With Iran’s primary nuclear facilities likely damaged or destroyed in previous attacks, what would a new round of strikes aim to achieve?

Many Iranians answer plainly: “We don’t know. We’re just exhausted.”

Reviewed by Tooba Khokhar and Celine Assaf

IAEA chief gets special police protection over threats as deadline approaches over Iran sanctions

Iran faces 'snapback' of sanctions over its nuclear program. Here's what that means

Executions, arrests and paranoia: Inside Iran’s crackdown on its own people after Israeli strikes

Palestinians flee Gaza City as escalating Israeli offensive kills 77

Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit could shed light on intentions of member states