This newsletter was first published in The Conversation UK’s World Affairs Briefing email. Sign up to receive weekly analysis of the latest developments in international relations, direct to your inbox.

It was “12 out of ten”, Donald Trump reported on emerging from his meeting with the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, in Busan, South Korea, this morning. It was the first time the two leaders have sat down face-to-face in since 2019 and a lot has happened to change the relationship between their two counties in the interim.

Particularly since April, when the US president launched his policy of applying punitive tariffs against countries he believes are “ripping off” the US, because of their trade imbalance. Trump’s policy placed Beijing firmly in the economic crosshairs. Having been gradually increasing tariffs in the first months of his second term on exports such as steel and restricting investors with links to China from investing in a range of important sectors, on Liberation Day, April 2, the US announced its plan to slap an extra 34% on export tariffs to China.

There followed a game of chicken, whereby each side saw the other’s announcement and raised them. At one point, US tariffs on exports to China reached 145%, while China raised theirs to 125%. Americans started to hurt: prices to ordinary consumers began to rise, something that Trump had campaigned on fixing, while farmers – a key Maga constituency – howled in pain when China stopped buying their soybeans. And the tech industry worried about China’s restrictions on the rare earth minerals they need to continue to manufacture so many high-tech products.

Thankfully that’s all fixed. For now. The two leaders emerged having agreed on a 12-month truce. China will start buying soybeans again and will relax many (not all) of its restrictions on rare earth minerals. The US will reduce its tariffs and relax some of its investment restrictions. Trump has said he will visit Beijing and Xi may well pay a visit to Mar-a-Lago.

But will this change the two countries’ trajectory? That’s hard to tell at this point, says Tom Harper, an expert in Chinese foreign policy at the University of East London. Fresh from catching up with details of the Busan meeting, he agreed to answer some of our key questions – namely: who will be happier, the two countries’ priorities, any remaining areas of tension and what appears to be the deliberate omission of any mention of either Taiwan or human rights.

This last point could be significant, marking as it does a major point of difference between the Trump administration and his predecessors going back decades, for whom a ticking off on the human rights front was always on the agenda.

Read more: What will Trump's deal with Xi mean for the US economy and relations with China? Expert Q&A

The analysis of the meeting between the two leaders released by China’s foreign ministry was revealing, in that while the US president’s post-meeting entry on TruthSocial celebrated the deals on soybeans, fentanyl and rare earths, China’s was more circumspect, stressing the country’s steady progress to a plan that had been in place for “generation after generation”.

Part of that plan involves self-reliance. “The Chinese economy is like a vast ocean, big, resilient and promising,” the foreign ministry commentary said. “We have the confidence and capability to navigate all kinds of risks and challenges.”

To be sure, writes Chee Meng Tan, an economist at the University of Nottingham, this ocean has had to weather some pretty serious storms of late. The vast real estate and infrastructure sector has been under huge pressure in recent years. So barriers to China’s export of manufactured goods – the other key component of Chinese economic growth – have also been extremely worrying for Beijing, even if, as Xi has insisted, the Chinese people are capable of “eating bitterness” (his way of saying that the people can thrive on hardship).

The continuing restrictions on Chinese access to US tech will also be a problem for Xi. China has set great store by its development into a high-tech behemoth and has telegraphed its intentions to become an AI giant in the next few decades. To do that, it either needs access to US know-how or will have to rapidly develop its own capabilities in the sector.

Read more: What will Trump's deal with Xi mean for the US economy and relations with China? Expert Q&A

Rise and fall of globalisation

It’s been fascinating over the past few years to watch the way global power has been shifting. Over the first 25 years of the 21st century, this has largely reflected two competing narratives. In 2000, when George W. Bush won his first term as president, his senior aides talked of a “new American century” dominated by Washington’s neo-conservative ideas. At the same time, in many people’s eyes, the 21st century seemed certain to be the “Asian century” as the region’s tiger economies woke up and began to fulfil their potential.

Xi’s meeting with Trump today and the two leaders’ apparently different approaches are the latest reflection of those competing narratives.

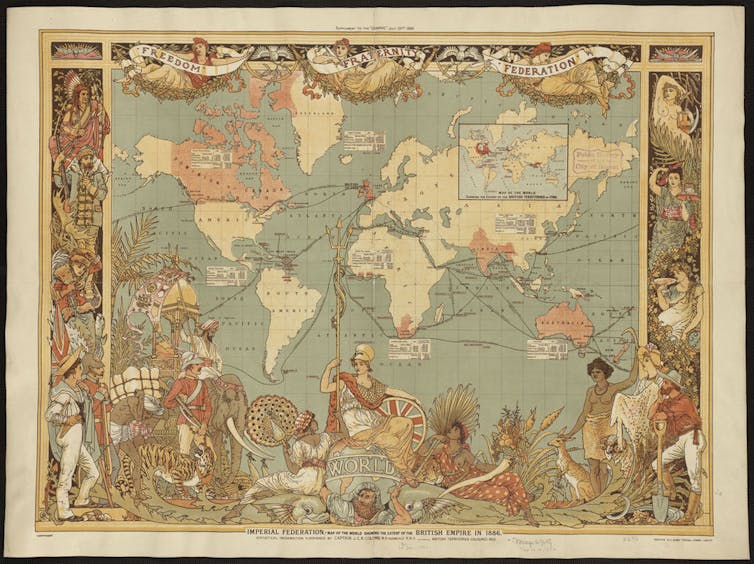

Steve Schifferes has been considering the global shifts in economic and political (and military) power that have shaped the world since the 16th century. Working with our Insights team, he has written a superb two-part analysis. The first instalment charts the rise and fall of the European mercantile empires and the irresistible rise of the US.

Read more: The rise and fall of globalisation: the battle to be top dog

Part two considers the likely consequences of the end of US hegemony, warning that the shift away from French and British dominance brought painful consequences and imagining what a world without a dominant world power might look like.

Europe scrambles to help Ukraine

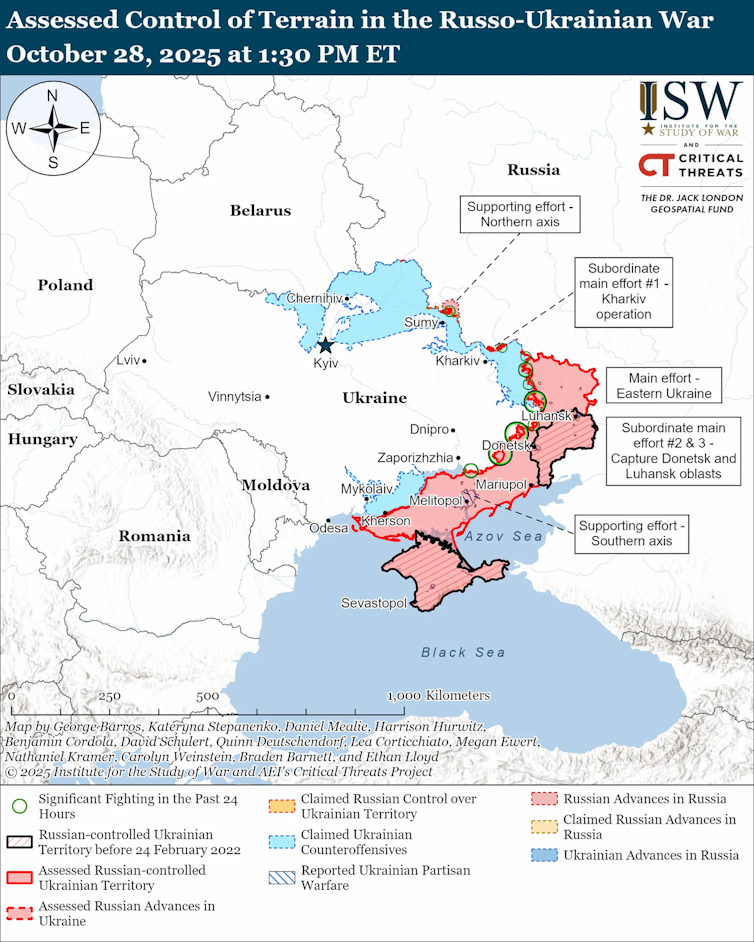

America’s apparent shift away from its old role as security guarantor in Europe has left its transatlantic Nato allies desperately trying to fill the vacuum. But, as Stefan Wolff and Richard Whitman point out, the fact remains that without US buy-in, Kyiv’s European friends are woefully short of the wherewithal to provide Ukraine what it needs to stem Russia’s advances on the battlefield.

Without substantial assistance, Ukraine will run out of money to fight this war next year, but talks at how to use the estimated €210 billion (£185 billion) in frozen Russian assets have stalled once again and the decision kicked down the road until December.

Like the US last week, Europe has announced a fresh package of sanctions – its 19th – against Russia in the hope that the considerable damage this conflict is doing to Russia’s economy will finally force Putin to the negotiating table. But that looks like a vain hope.

As Wolff and Whitman conclude: “There’s mounting evidence suggesting that [Europe] will not stretch themselves to go beyond securing Ukraine’s immediate survival. Unsurprisingly, a credible pathway to ending the war with a just and stable peace is still lacking.”

Read more: Ukraine: another week of diplomatic wrangling leaves Kyiv short of defensive options

Sign up to receive our weekly World Affairs Briefing newsletter from The Conversation UK. Every Thursday we’ll bring you expert analysis of the big stories in international relations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.