With only two days to go before the expiry of his latest ultimatum to end the Russian aggression against Ukraine, the US president, Donald Trump, dispatched his envoy Steve Witkoff to Moscow for the fifth time on August 6. After three hours of talks in the Kremlin between Witkoff and the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, Trump announced on social media that “Great progress was made!”

According to the US secretary of state, Marco Rubio, this includes a Russian ceasefire proposal that Witkoff is bringing back from his meeting with Putin. At a subsequent press conference, Trump indicated that he could soon meet in person with Putin and his Ukraine counterpart, Volodymyr Zelensky.

However, there was no indication of an imminent breakthrough in the US president’s quest for a ceasefire. While, during a phone call with Zelensky and European leaders, Trump appeared optimistic that a diplomatic solution was possible, he said it would take time.

Rubio also expressed caution, noting that “a lot has to happen” before a Trump-Putin-Zelensky summit, as there are “still many impediments to overcome”.

For once, Trump appears to realise he will only make progress on ending the war if he maintains the pressure on Putin. Shortly after the meeting between Putin and Witkoff, Trump issued an executive order stating: “The actions and policies of the Government of the Russian Federation continue to pose an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States.”

This is hardly surprising, given that Trump’s frustration with Putin has steadily built up since the end of April. Increasingly viewing Putin as the main obstacle to peace in Ukraine, Trump has given the Russian president until August 8 to agree to a ceasefire.

Economic sanctions

Failure to comply would, Trump said, lead to severe economic disruption for Russia’s war economy. If activated, US sanctions are likely to target Russia’s so-called shadow fleet of oil tankers that the Kremlin uses to sell oil at prices above the G7-imposed price cap of (currently) US$60 (£45) per barrel.

The US president is also considering the imposition of 100% tariffs on imports from countries still buying Russian oil. This would particularly affect China and India, Russia’s largest costumers. If Beijing and New Delhi were to decrease their oil imports, it would deprive the Russian war economy of much-needed revenue.

But this is a big “if”. There are serious doubts that China can easily be pushed to wean itself off Russian oil supplies.

India has indicated that it will not bow to US pressure. While trade negotiations between Washington and Beijing are ongoing, talks with India have broken down for the time being.

But, as a likely indication of Trump’s determination to get serious on increasing pressure on the Kremlin and its perceived allies, the US president has imposed an additional 25% tariff rate on Indian imports to the US. This will be on top of the existing 25% rate, and will come into effect within three weeks.

China and India might continue to publicly resist US pressure. But, given the billions of dollars of trade at stake, they might try to use their influence with Putin to sway him towards at least some concessions that may lead to a ceasefire. This could give both Trump and Putin a face-saving way out – albeit not one that would move the dial substantially closer to a peace agreement.

There is also the question how Russia would respond – and concessions do not appear to be foremost on Putin’s mind. Expect more nuclear sabre rattling of the kind that has become the trademark of Dmitry Medvedev, the former Russian president and now one of the Kremlin’s main social media attack dogs.

Such threats were mostly ignored in public in the past. But in another sign of his patience wearing thin, Trump responded to Medvedev’s latest threat by ordering “two Nuclear Submarines to be positioned in the appropriate regions, just in case these foolish and inflammatory statements are more than just that”.

Military muscle

Neither the Kremlin nor the White House are likely to go down the path of military, let alone nuclear, escalation. But like Washington, Moscow has economic levers to pull too.

The most potent of these would be for Russia to disrupt the Caspian oil pipeline consortium, which facilitates the majority of Kazakh oil exports to western markets through Russia. If completely shut down, this would affect around 1% of worldwide oil trade and could lead to a spike in prices that negatively affects global economic growth.

Trump’s economic statecraft will probably produce mixed results at best – and only slowly. But the US president has also recommitted to supporting Ukraine militarily – at least by letting Kyiv’s European allies buy US weapons. Germany was the first to agree the purchase of two much-needed Patriot air defence systems from the US for Ukraine.

Since then, this new way of funding arms for Ukraine has been formalised as the so-called Prioritised Ukraine Requirements List.

It will require substantial financial commitments from Nato countries to turn this new support mechanism into a sustainable military lifeline for Ukraine. But the scheme got off to a relatively smooth start with the Netherlands and three Scandinavian members of the alliance – Denmark, Norway and Sweden – quickly following in Germany’s footsteps.

These recent developments indicate Trump has finally accepted that, rather than trying to accommodate Putin, he needs to put pressure on him and his backers – both economically and militarily.

If the US president wants a good deal, he needs more leverage over Putin. Weakening Russia’s war economy with further sanctions and blunting the effectiveness of its military campaign by arming Ukraine are steps that might get him there.

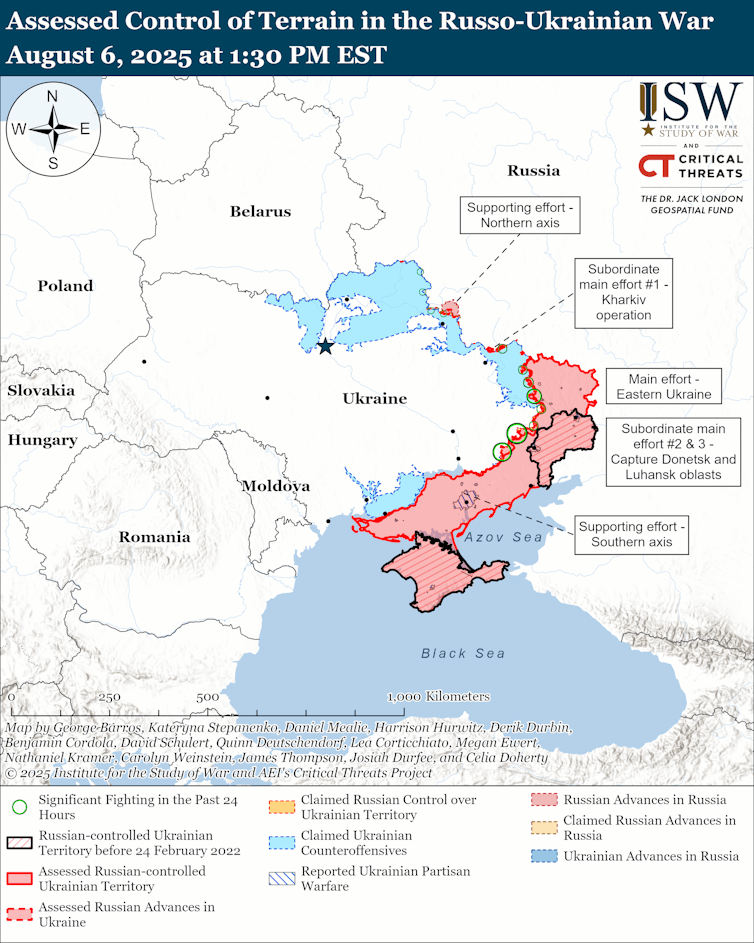

When and how the war in Ukraine ends will ultimately be determined at the negotiation table. But how soon the belligerents get there – and what the balance of power will be between them – will be decided on the battlefields of eastern and southern Ukraine.

Stefan Wolff is a past recipient of grant funding from the Natural Environment Research Council of the UK, the United States Institute of Peace, the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the British Academy, the NATO Science for Peace Programme, the EU Framework Programmes 6 and 7 and Horizon 2020, as well as the EU's Jean Monnet Programme. He is a Trustee and Honorary Treasurer of the Political Studies Association of the UK and a Senior Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Centre in London.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.