The shape of the universe is not something we often think about. But my colleagues and I have published a new study suggests it could be asymmetric or lopsided, meaning not the same in every direction.

Should we care about this? Well, today’s “standard cosmological model” – which describes the dynamics and structure of the entire cosmos – rests squarely on the assumption that it is isotropic (looks the same in all directions), and homogeneous when averaged on large scales.

But several so-called “tensions” – or disagreements in the data – pose challenges to this idea of a uniform universe.

We have just published a paper looking at one of the most significant of these tensions, called the cosmic dipole anomaly. We conclude that the cosmic dipole anomaly poses a serious challenge to the most widely accepted description of the universe, the standard cosmological model (also called the Lambda-CDM model).

So what is the cosmic dipole anomaly and why is it such a problem for attempts to give a detailed account of the cosmos?

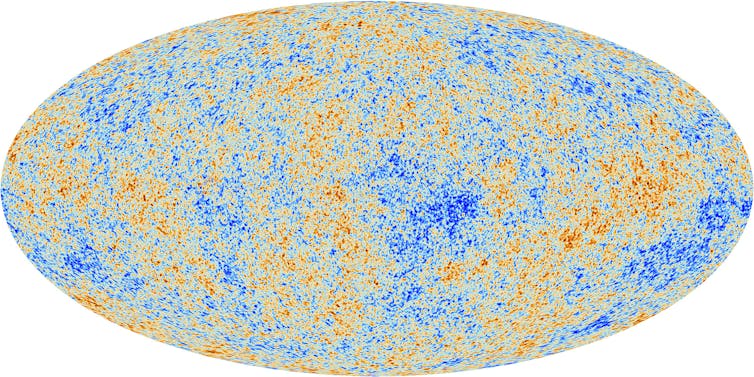

Let’s start with the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which is the relic radiation left over from the big bang. The CMB is uniform over the sky to within one part in a hundred thousand.

So cosmologists feel confident in modelling the universe using the “maximally symmetric” description of space-time in Einstein’s theory of general relativity. This symmetric vision for the universe, where it looks the same everywhere and in all directions, is known as the “FLRW description”.

This vastly simplifies the solution of Einstein’s equations and is the basis for the Lambda-CDM model.

But there are several important anomalies, including a widely debated one called the Hubble tension. It is named after Edwin Hubble, who is credited with having discovered in 1929 that the universe is expanding.

The tension started to emerge from different datasets in the 2000s, mainly from the Hubble space telescope, and also recent data from the Gaia satellite. This tension is a cosmological disagreement, where measurements of the universe’s expansion rate from its early days don’t match up with measurements from the nearby (more recent) universe.

The cosmic dipole anomaly has received much less attention than the Hubble tension, but it is even more fundamental to our understanding of the cosmos. So what is it?

Having established that the cosmic microwave background is symmetric on large scales, variations in this relic radiation from the big bang have been found. One of the most significant is called the CMB dipole anisotropy. This is the largest temperature difference in the CMB, where one side of the sky is hotter and the opposite side cooler – by about one part in a thousand.

This variation in the CMB does not challenge the Lambda-CDM model of the universe. But we should find corresponding variations in other astronomical data.

In 1984, George Ellis and John Baldwin asked whether a similar variation, or “dipole anisotropy”, exists in the sky distribution of distant astronomical sources such as radio galaxies and quasars. The sources must be very distant because nearby sources could create a spurious “clustering dipole”.

If the “symmetrical universe” FLRW assumption is correct, then this variation in distant astronomical sources should be directly determined by the observed variation in the CMB. This is known as the Ellis-Baldwin test, after the astronomers.

Consistency between the variations in the CMB and in matter would support the standard Lambda-CDM model. Discord would directly challenge it, and indeed the FLRW description. Because it is a very precise test, the data catalogue required to perform it has become available only recently.

The outcome is that the universe fails the Ellis-Baldwin test. The variation in matter does not match that in the CMB. Since the possible sources of error are quite different for telescopes and satellites, and for different wavelengths in the spectrum, it is reassuring that the same result is obtained with terrestrial radio telescopes and satellites observing at mid-infrared wavelengths.

The cosmic dipole anomaly has thus established itself as a major challenge to the standard cosmological model, even if the astronomical community has chosen to largely ignore it.

This may be because there is no easy way to patch up this problem. It requires abandoning not just the Lambda-CDM model but the FLRW description itself, and going back to square one.

Yet an avalanche of data is expected from new satellites like Euclid and SPHEREx, and telescopes such as the Vera Rubin Observatory and the Square Kilometre Array. It is conceivable that we may soon receive bold new insights into how to construct a new cosmological model, harnessing recent advances in a subset of artificial intelligence (AI) called machine learning.

The impact would be truly huge on fundamental physics – and on our understanding of the universe.

Subir Sarkar receives funding from the UK Research & Innovation (UKRI) councils.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.