When you have a kid with a severe illness, whatever makes them happy during it becomes immeasurably valuable to you—no matter how small.

I learned this when my 1-year-old son, Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumor. As part of his treatment, he had to get a tracheostomy—a breathing tube was inserted in the base of his neck and prevented him from talking. After he lost his voice, Henry communicated through Makaton, a language program that uses symbols, signs, and speech to enable communication for people who might otherwise have a tough time being understood. The program is similar to sign language, but it combines hand gestures with spoken words (for those who can speak) and sometimes references to images or objects as well. Many people with Down syndrome find it helpful, as do kids like Henry who can’t speak because of a tracheostomy and nerve damage.

You may have seen Makaton if you’ve ever watched the beloved Mr. Tumble on CBeebies, a BBC channel for little kids. Mr. Tumble is the alter ego of a guy named Justin Fletcher. Because he’s probably the most famous Makaton user in the United Kingdom, he’s helped countless families develop communication skills that foster substantively better and closer relationships. When we found his show, Henry and I didn’t have much longer left together, but Mr. Tumble helped us understand each other in what time we did have. It is fair to say that I love Mr. Tumble. One time, I heard a mom talking about her preferred CBeebies shows, and she said she didn’t like Mr. Tumble. I had to walk away. Fuck with Mr. Tumble, and you fuck with me! She’s lucky I had errands to do and didn’t have time to go to jail that day.

I’ve yet to meet Mr. Tumble, but I have had the good fortune to meet Singing Hands, who probably brought Henry the most joy out of anything in his sweet little life. Singing Hands are Suzanne Miell-Ingram and Tracy Upton, two wonderful women who (among many other things) have their own channel on Great Ormond Street Hospital’s televisions. They perform all sorts of songs and nursery rhymes using Makaton and their lovely singing voices. The second we found their channel, Henry was hooked. We watched Suzanne and Tracy sing each song again and again, and Henry and my wife, Leah, and I practiced signing along. It was so goddamn fun. And Henry was great at it. His tumor and surgery affected only his physical skills; they had no noticeable effect on his brain’s frontal lobe. So he was as alert and curious and driven as any other kid. Memories of him like this are some of my most treasured.

One day, I was down in the hospital’s cafeteria and did a double take. Tracy from Singing Hands was there, sitting at a table, just like a normal civilian might. I took a deep breath and approached her with the mix of purpose and humble deference with which a person might approach Sir Paul McCartney. I told her I was one of, I’m sure, thousands of parents whose ability to communicate with their child was directly improved by her beautiful work. She didn’t ask me to please back away from her table, but rather was happy to hear about Henry, and about how her and Suzanne’s work had affected us. She even asked if she could come up to Henry’s room and meet him. And meet him she did. Henry was agog. He was confused at first, like anyone would be if one of the coolest people in existence essentially walked out of the television, but kids adapt fast, so he soon achieved equilibrium. He was so happy to sign “Itsy Bitsy Spider” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and other nursery rhymes with her. So was I! I still remember what his smile looked like on that day.

A little less than a year after Henry died, I was asked to read the CBeebies Bedtime Story. If you’re not British, you should know that CBeebies probably does at least 25 percent of the U.K.’s parenting. It does it well, too. Its programming is excellent—high quality and educational. Shows like Something Special, Hey Duggee, and Bluey entertain kids (and adults) with wildly creative, sensitive, stimulating shows—and they’re not interrupted by commercials. At the end of each programming day, at 6:50 p.m., a different celebrity reads a story before they say goodnight. Ever since I moved to the U.K. in 2014 to act and write for the show Catastrophe, I’d wanted to do a CBeebies reading. I asked if I could do my story in Makaton.

CBeebies was happy to oblige, and I was surprised to learn that mine would be the first ever Makaton Bedtime Story. We’d agreed that Penny Dale’s version of Ten in the Bed would be a good book to do in Makaton. I practiced in the days leading up to the recording, and on the appointed day, I went to the London hotel in which we’d record. They had me on the edge of a bed with the 10 necessary stuffed animals perched across it. They also provided a Makaton coach, who made sure I did all the signs perfectly. The recording went reasonably well until I had to sign and say the phrase “I’m cold and lonely.” I started to cry. It just shook me to know that I’d be doing a book that Henry loved, using the method of communication I’d eagerly learned for him, and he wasn’t alive to see it. I was desperate to get it on TV so other families could watch it and use it, but it hurt terribly to do something he’d have enjoyed so much. The producer said we could take a break if I wanted to, and I said no, I am crying because I miss my son Henry. I learned Makaton for him and now he’s dead. So I am going to take a few deep breaths and we can continue filming.

I didn’t mean to chastise a lovely person for humanely and very understandably offering me a break; I just knew that disabled kids and their families deserved their first Makaton Bedtime Story, and it was our job to get it on the air. It was one of those instances when I felt that the show, as it were, must go on.

It did, and when that Bedtime Story went out, people really loved it. Seeing the happiness it brought kids and parents who need Makaton to communicate flooded me with love and gratitude for my sweet, blessed Henry. His death and physical absence cause me great and enduring pain, but I feel his presence and effect on the world when families with sick and/or disabled kids get a smile out of something Henry taught me. During his life, I always knew shows like these carried power for me, because of how much happiness they brought him. But I wasn’t prepared for how much they would continue to mean even after he was gone—helping me the way they once helped Henry.

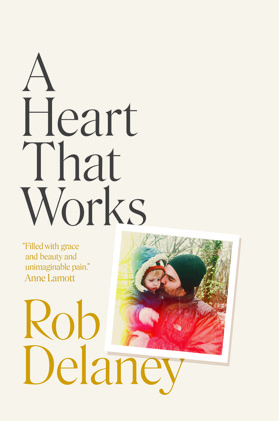

This article has been excerpted from Rob Delaney’s new book, A Heart That Works.