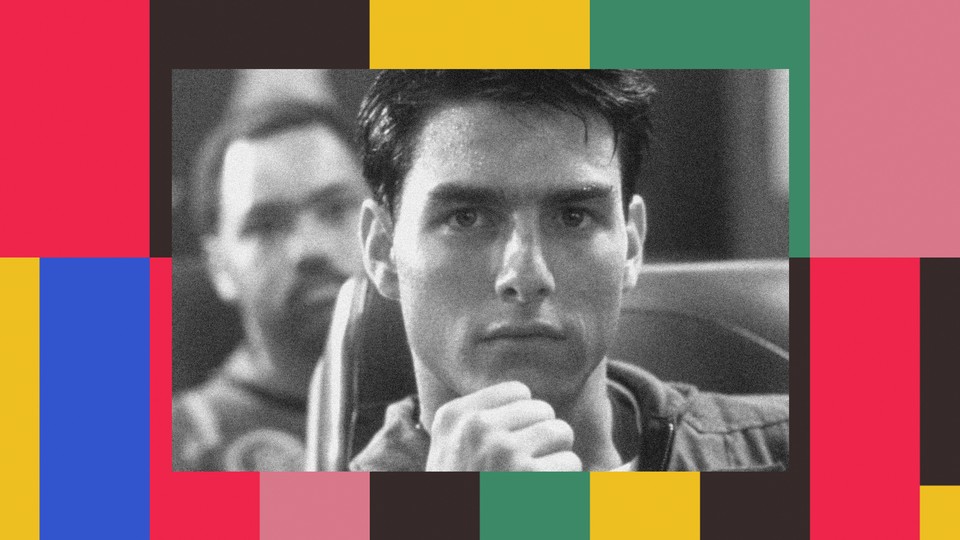

Top Gun: Maverick is out soon! But can any movie with fast planes, Tom Cruise, and beach volleyball truly compare to the classic fighter-pilot movie about, as writer Shirley Li puts it, “cute boys calling each other cute names”? And do audiences have an appetite anymore for what Megan Garber called an “infomercial for America”? Find out with Shirley, Megan, and David Sims, and explore the moral (but fictional) simplicity of an earlier era: the Cold War ’80s.

Listen to their discussion here:

The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

David Sims: The movie Top Gun: Maverick, the sequel to Top Gun, is finally coming to theaters after getting delayed many, many times by the pandemic. Its initial scheduled release date was July 12, 2019. They delayed it ’til June 2020, more for genuine reshoots and production reasons. And then, of course, because of the coronavirus pandemic, it got kicked to July 2021, and then it got kicked to November 2021, and then it got finally moved to when it is actually being released: May 27, Memorial Day Weekend 2022. So this is one of the last delayed-by-COVID movies to make it to the big screen. It’s been this sort of story for Hollywood blockbusters for a couple of years now. And here Top Gun: Maverick is. It really feels like a movie that was made before the pandemic. Megan, you wrote about it for the magazine, and I think the headline in your piece was “Top Gun is an Infomercial for America.”

Megan Garber: Yeah. So I, too, grew up with Top Gun in the air, as it were. I don’t remember exactly when I watched it for the first time—definitely not in theaters—but I sort of had the detritus of that movie as part of my childhood. Like in toy stores, there were, like, 14 toys you could buy, and there was an amusement park near my house that had eventually a Top Gun–themed ride where you just listened to “Danger Zone” on a horrifying loop as you waited. But as a film, I had not really thought about it for many years until going back to reconsider it for this story. And yeah, it really did strike me how much of the film works as an ad. And I don’t just mean that in terms of propaganda, although definitely that is part of it, but an ad in the sense that it is selling something at every juncture; an ad will sort of strip away the context and the complications of the world until all that’s left is naked need. And, you know, a big blob of want.

That’s what this film really does, and I think really successfully, for better or for worse, as we can talk about. And then also infomercials in particular, I think, try to foster this very direct dialogue with their audiences. They try to have a discourse that will last for an hour, or whatever the length of the infomercial is, to anticipate the viewers saying no to the product, and instead it will say “No, here’s why you’re wrong. You’d think that this knife will not cut through wood. But wait, we will show you how this knife is going to cut through wood.” And every time the viewer might have an objection to the thing being sold or a question about whether the thing being sold is true, the infomercial will say, “Actually, let us tell you a little bit more.” And I think Top Gun definitely does that. You think at first maybe Maverick’s kind of a jerk, because he kind of is. But wait, there’s more. He’s also grieving and complicated and a romantic hero. And at every turn, Top Gun is using the logic of the advertisement to share its artistic message.

Shirley Li: Yeah, I love this. I hadn’t thought about it as an ad versus an infomercial-type film. It’s like, aren’t you just as hyped as Maverick is when he is riding his bike next to the fast-zooming planes? And so you kind of want to toss your fists up in the air. That’s very infomercial.

Garber: And it can be yours for four easy payments of $19.99. It’s all so easy.

Sims: The film is directed by Tony Scott, who’s the slightly flashier, less critically respected brother of Ridley Scott, although in my opinion, Tony Scott is one of Hollywood’s great auteurs of ’80s and ’90s trash cinema. But he came out of commercials, as did Ridley Scott. Of course, there were a lot of filmmakers in the ’80s, especially, strangely, out of Britain—Alan Parker’s another one—these guys who had cut their teeth doing a hard sell. Ridley Scott had a famous ad for Hovis Bread, obviously had this famous Apple ad. It was just not happening in Hollywood. Like, why would a commercial director move to features? But then it becomes the template for these big action with Michael Bay, David Fincher, these guys who make commercials as ways to show off how muscular their storytelling can be, you know, like how quickly you can sell someone on a guy or a concept or a product or country.

Obviously it was an enormously successful film. It’s such a weird movie because it’s so gung ho. It’s about the Navy, and it’s about the military and all this. But the enemy is oblique; like, who is the enemy? We don’t even really understand who they’re fighting against. It doesn’t really matter. It’s more about victory. We are the best of the best. We have lessons to learn, but that’s how America works, and we’re going to triumph. Because I guess we’re not in World War II or even Vietnam. It’s this military movie where the enemy doesn’t matter.

Garber: I think that’s part of what’s being sold: the simplicity of the enemy, just in the sense of “You don’t have to think about the enemy.” You don’t have to consider anyone but the person who’s in that plane. And I think for viewers, there’s something that can be reassuring about that, because you don’t have to consider the broader moral complexities of war. You don’t have to consider context really at all. So I think there is a way that this movie can work as a metaphor for a lot of American approaches to geopolitics. And watching it especially recently, you think about Ukraine, for example, and all the images that we’re seeing—just the fact of the war happening there—and then watch a movie that does so much to elide those tragic realities and essentially treat war as a game.

Li: I think you hit the nail on the head there. It’s the kind of film that we’ve been doing forever when it comes to talking about the context of war. It flattens that imagery to the point that you don’t really know who the enemy is. You don’t need to know their motivations. I just wanted to point out that Top Gun, in my mind at least, is about a bunch of cute boys calling each other cute names.

Sims: That’s very true.

Li: But what it actually is is a story about some hotshot Navy fighter pilots. They’ve got these cute names that are called call signs. They’ve got names like Maverick and Goose and Hollywood. Iceman.

Sims: Yeah. Cougar. Viper.

Li: Thank you. So Cruise is Maverick. He’s pretty arrogant. He’s kind of cocky, right? He is a naturally skilled fighter pilot, whatever that means. Maverick goes off to Top Gun, which is this elite flight school that the film outlines, and is where he and his classmates can learn “the lost art of aerial combat.” And they all get to compete for the Top Gun trophy, which would cement them as the best. The fighter pilot, in the meantime, also falls in love with his instructor, the only female character of any consequence in the film, played by Kelly McGillis. Her name is Charlotte, yes, but she’s called Charlie and she knows a lot about planes. So he learns life lessons, he makes mistakes, etc.

Sims: Right. It has the mechanics of the high-school drama, and also the very classic “monomyth” sort of thing. He’s the chosen one, but he must learn from his mistakes and he must face this low point and face tragedy and then rebound. It’s a very familiar arc.

Li: Yeah, it is very high school.

Garber: There’s also a way to think of it perhaps as a Western, like a lot of the themes, of the individual versus the collective, law versus lawlessness, and all that kind of stuff. Even just the fact that his call sign is Maverick—the cow that wouldn’t join the herd.

Sims: It’s a Western with more rules, because technically they are at school; they’re being instructed. They’re not supposed to just fly their planes whenever they want. This guy’s a rule breaker, but also he’s going to Navy school, so he’s not a rule breaker; he’s a pioneer going out into the great unknown. Like, there’s a little bit more of a safe veneer over the whole thing.

Garber: Totally. And I think one element of that is the fact that Maverick is this character who in one way embodies rugged individualism, with all the mythology around that kind of stuff. He’s so talented. He’s an intuitive flier, as they say again and again.

So watching the movie, one of my maybe shameful reactions is that I felt myself identifying so much more with Iceman than with Maverick, and I don’t know if that says bad things about me as a person. But I just kept thinking, You know, Iceman is right.

Like, yes, he is set up as the villain of this movie. And yes, in some ways he is quintessentially villainous. And yet at the same time, I think if I were on that squadron, I would feel exactly like Iceman. I would not want to be flying with someone like Maverick who will just go rogue whenever he decides to, who will be your wingman and then just leave you without any real reason. It just seems like these are literally life-and-death situations. And I would be happy to hang out with Maverick, but I would actually not want him as a colleague in that situation. I would want Iceman, even though I know he’s set up as the villain. And I think in a lot of ways he does represent, per the Cold War setting, the Soviet style of being very mechanistic and soulless and collective above all. And I know that was set up as a negative here, but I did feel like maybe he’s the hero of this movie.

Sims: I agree with you that he’s basically right in that he’s like, “Maverick, stop being such a maverick. Like, we’re here to learn, and this is a matter of life and death.” But he just represents the rules Maverick has to break to achieve his own emotional fulfillment. A maverick has to realize truths about himself. And that is very American of him: He has to break rules, and maybe people are going to die. At the end of the day, he's going to kind of get a pat on the back and a sort-of-weird apology, or it’s not even an apology but the scene where Iceman tries to express some sort of sadness, but he can’t, really. Where they had that in the locker room is honestly palpable. They’re such high-strung men, they can’t really admit any weakness. And the closest Iceman can do is just tail off.