Mortal Kombat Legacy Kollection is so much more than just a game compilation; it’s a well-researched and intensely detailed look at the creation of the series and the people behind it.

Digital Eclipse has made a name for itself with compilations like the Mega Man Legacy Collection and the Samurai Shodown NeoGeo Collection. But the studio has taken a different tack in recent years, doubling down on the idea of not just re-releasing games, but preserving them and demystifying how they were made. To that end, the developer coined the term “interactive documentary.”

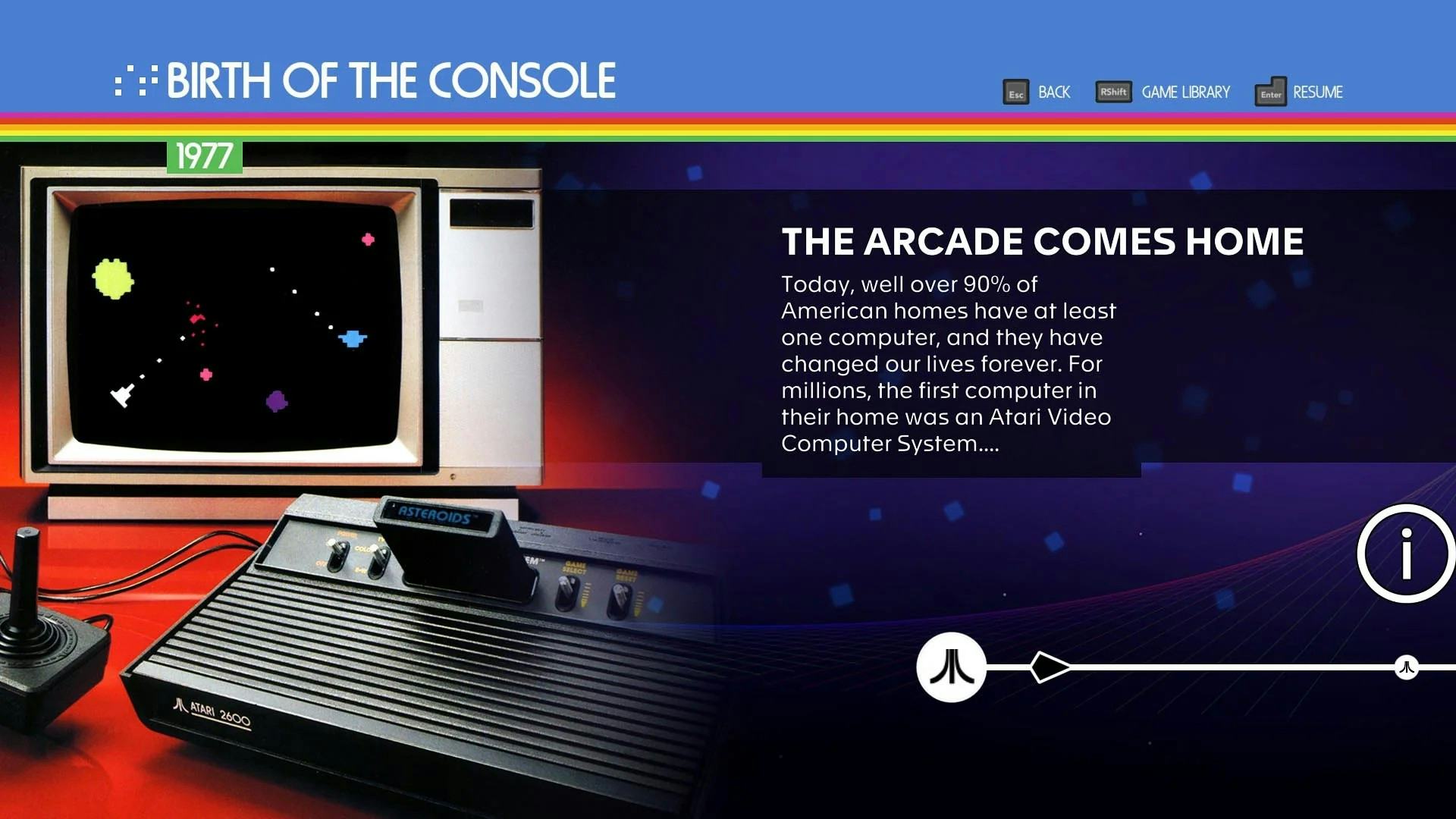

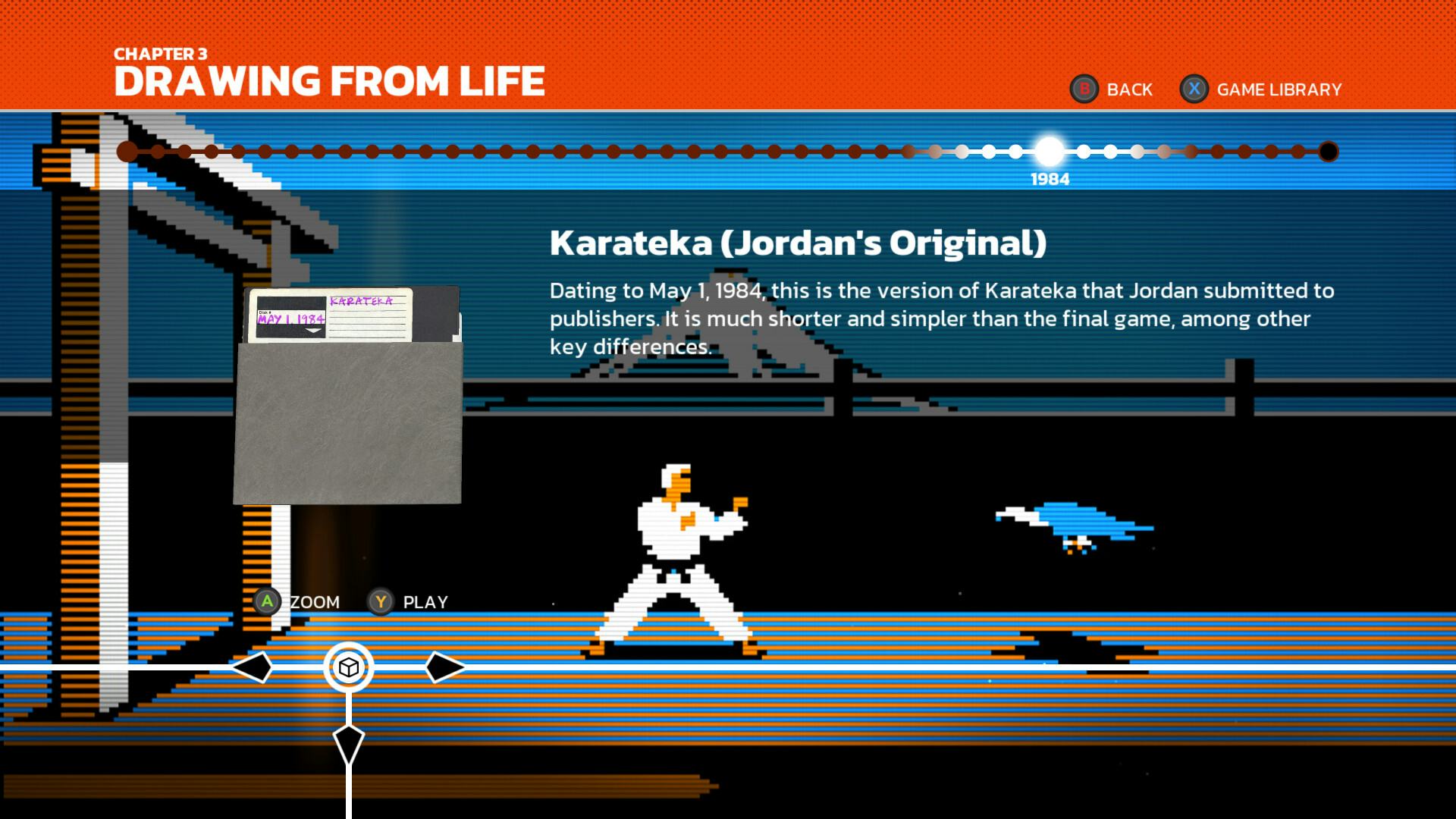

Games like Atari 50: The Anniversary Celebration and The Making of Karateka shine a light on video game history by integrating interactive galleries and hours of documentary footage, and Digital Eclipse is hopeful that this style might push the industry to be better about preservation efforts.

“The more companies we work with, Konami and Capcom or even folks we might not have worked with yet, they’re starting to understand the importance of what we do and the things we’re looking for,” Digital Eclipse head of production Stephen Frost tells Inverse. “Then they start to protect that stuff much earlier. So I think the positive impact we have on the industry, I hope, is that more companies are broadly aware of how it’s important to keep things, and you should start spending time gathering stuff early. Not just if you plan to work with us, but at some point you’re going to need it.”

While their previous games might have flown under the radar, Digital Eclipse is hopeful that Mortal Kombat Legacy Kollection could represent a turning point for the importance of the studio’s preservation efforts.

In a two-part interview (read the first part here), Inverse talked to Frost, content editor Dan Amrich, and editorial director Chris Kohler, who dove into Digital Eclipse’s mission of preservation and how Mortal Kombat marks a new era for the studio.

This interview had been edited for clarity and brevity.

The legacy of fighting games is often different from other genres, because of the competitive scene and arcade machines. Was that something you were cognizant of while developing Mortal Kombat Legacy Kollection?

Amrich: Early on, we thought about who our target audience was. Who do we want to tell the story to? And fighting games do have that challenge because the fighting game community is so passionate, and working on so many levels of so many games at the same time.

Our producer on this project, Steven Johnson, has been involved with the fighting community for many years, he organizes tournaments and everything. So I thought we would lean into the competitive scene, and that wasn’t really the direction I felt we should go. So to have Steven say oh no, this should be about the people who remember playing this with their cousin, that kind of thing… we ended up leaning more toward the wide pop culture appeal, rather than the intense competitive community.

We had to come to that crossroads early in the project, and we realized there’s so many more people that have such strong, happy memories of ripping somebody’s spine out with their brother, or whatever. That was the way to go.

Frost: It’s a fine balance for sure, because modern MK is designed for fighting game fans, right? And we’re trying to appeal to a broad audience. Of course, we can’t ignore game fans, but in a collection, it’s impossible to build out the full experience that a single modern fighting game is. We have multi-purpose goals for a lot of what we do.

Like the fighting game community might see training modes and say, that’s for us. But also, for people who are relatively new or casual players, it allows them a safe place to just come in and mess around to learn the mechanics. So it serves a double purpose.

Do you think video games have a preservation problem? Are we going to be able to make collections with contemporary games 20 to 30 years from now?

Kohler: If we’re able to do this 20 to 30 years from now, I’m hoping that Mortal Kombat Legacy Kollection is one of the major waypoints in that journey. That we’re able to present this concept on a bigger stage and introduce how we’re trying to rethink, and hopefully trying to expand the audience, for re-releases of classic games.

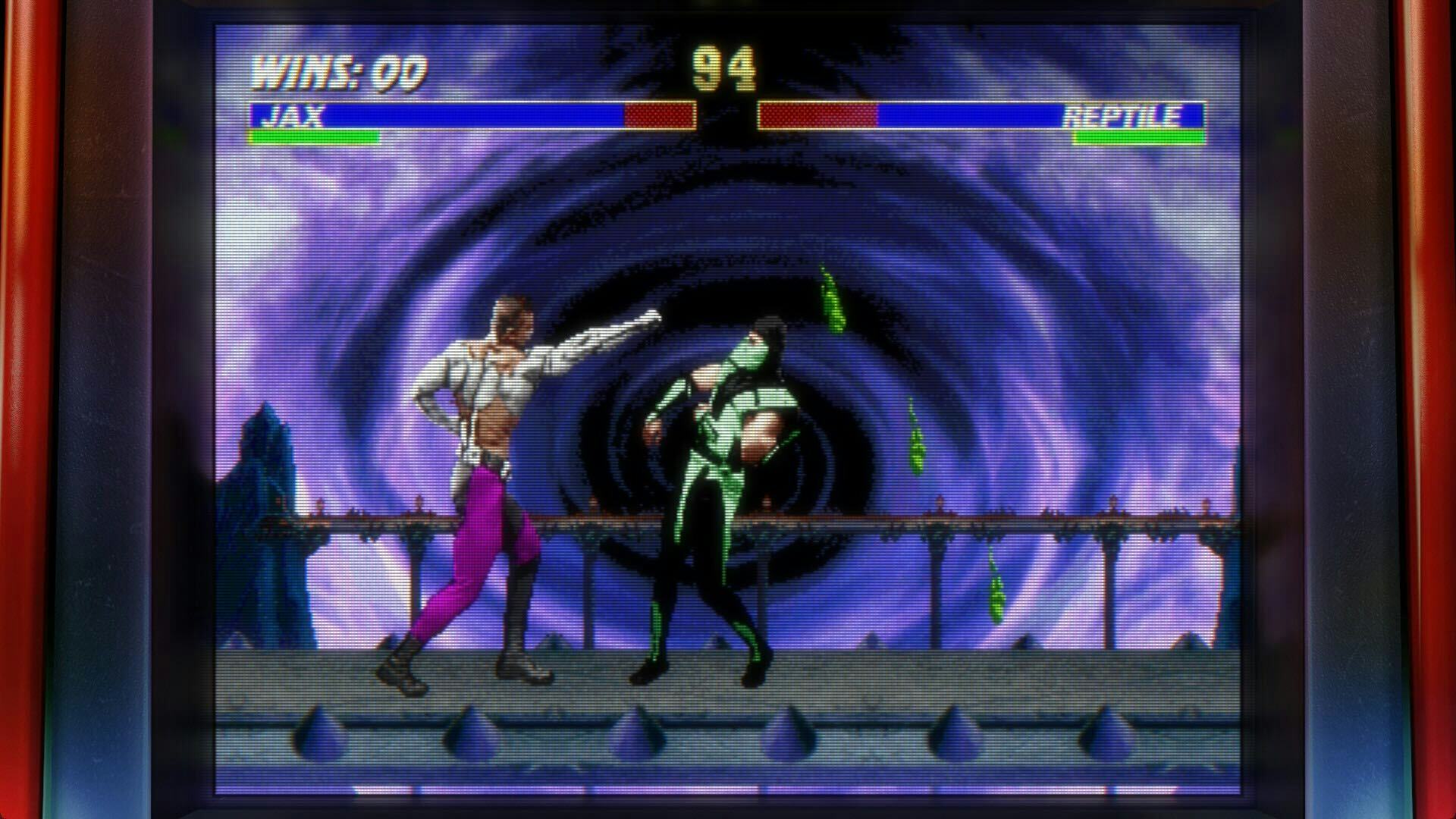

What we are doing, as you know, is officially licensed commercial releases. We’re all cognizant of what role we can play in preservation. I think if you look at the release of Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3’s WaveNet version, this is something that even fans, even through unofficial methods, have not been able to do. When there is an incentive to make it happen, and we can put all of these resources into it, working in concert with Netherrealm to make it happen for folks – I think you put that in the “win” mark for preservation.

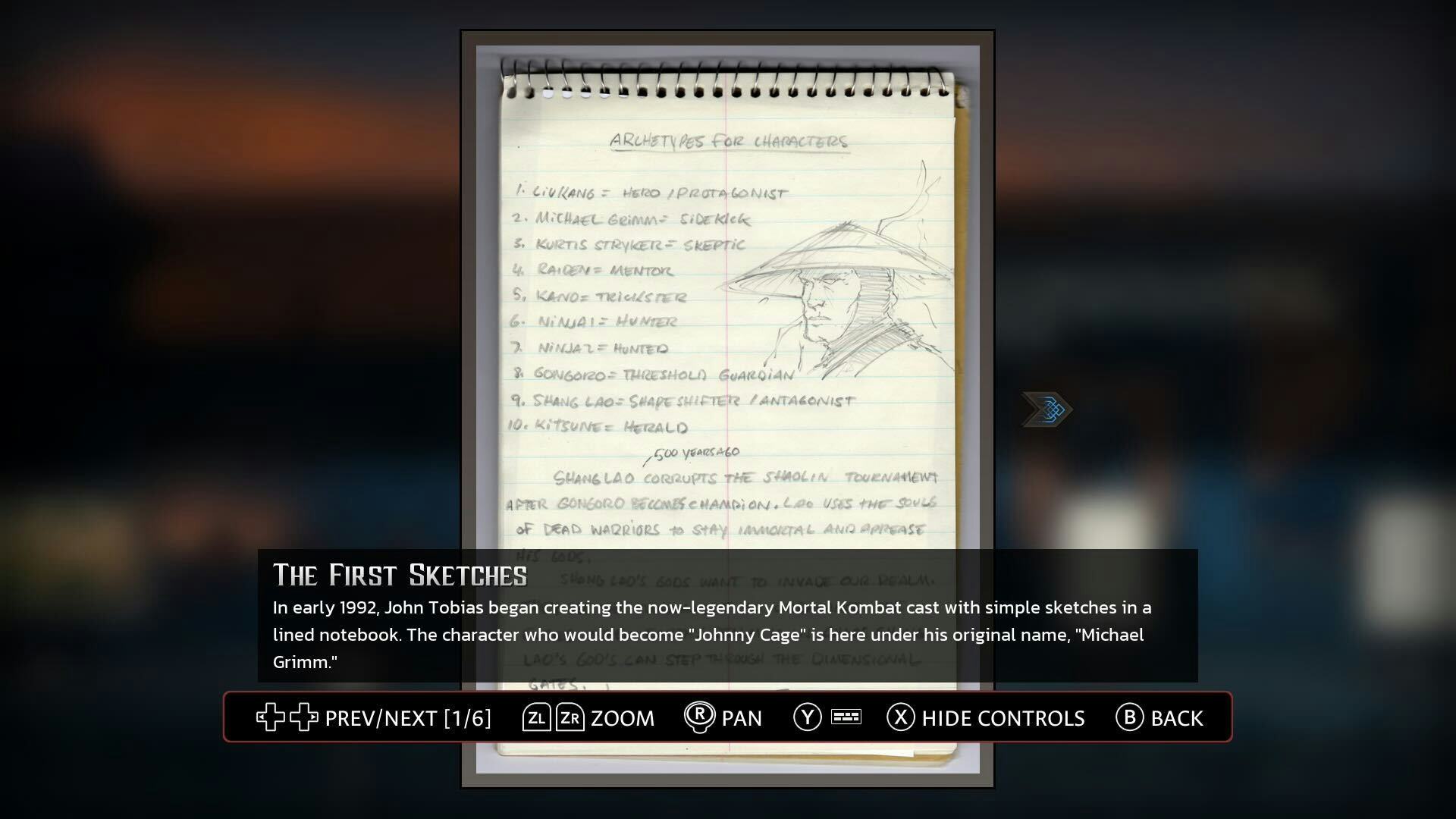

When there are things that are scanned on pieces of paper in somebody’s garage that may never see the light of day, but for the fact that we are putting something like this together and we’re banging down the door trying to get it – again, it’s not just the fans asking for a commercial product that are going to benefit, it’s everybody.

We feel like we’ve got this opportunity, like with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Cowabunga Collection. Konami came to us after we were making our asks for behind-the-scenes materials, and they were showing us, on a Zoom meeting, literal physical binders of materials. They’re like, “This is what we have for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Tournament Fighters. What should we scan?” And we say everything, every last page in that binder, because they know it, we know it, everyone knows it – this could be the last golden chance to do it. This could be the one and only chance. Konami historically lost some things when there was a fire at a facility, so you really don’t know if there’s going to be a tomorrow.

You take that opportunity when you can, and you do it in a way that’s complete. And maybe you’re not reading every single one of those things, but I like to think that something like that may be a very valuable resource for historians down the line.

Frost: I’m very proud of us from a company and studio perspective, in that we’re always forward-thinking, and the Cowabunga Collection is a great example of that. There are so many assets that we actually built in a search engine, so that someone years from now writing a story about classic Turtles games can go in, do a search, and see all these assets in an easily accessible way.

Number two, since we’re very emulation-based in the way our architecture works, we should have a much easier time in the future years from now on new platforms. We want to copy movies from the standpoint that with every new platform for movies, you’re going to see Casablanca and The Godfather, these movies don’t disappear. But you don’t see that in games often, right?

So we want to make sure that when we build this stuff, and the way we build this stuff, that 10 years from now on PlayStation 7, we could re-release the Mortal Kombat Legacy Kollection, if someone wants that. We could do that and continue that sort of education and awareness for future generations.

Amrich: I was working in the media in the early '90s, covering arcade games and doing cover stories on Mortal Kombat 3 and such when it was coming to PlayStation. So I actually was talking to [series co-creators] Ed Boon and John Tobias way back when these games were new. I remember contacting Midway, Roger Sharpe, the pinball legend, was their PR guy and their licensing guy. I had no idea who I was talking to or how important he was to the history of the industry. At that point, he was the guy who’d send me flyers and screenshots when I needed them. And I said, “Hey, what do you think about doing a Mortal Kombat book, because it feels like these first three games hold together as a set, and I understand you’re moving into 3D. I could help.” He goes, “Sounds good, send me a pitch.” I never did, and it was honestly one of my big career regrets.

So it’s been a gift to be able to go back to these same people and say, remember me from 30 years ago? But wind up telling a much richer, more intense version of that story. Now we have the wisdom of what the social impact of this is 30 years later.

We got two dozen people on camera from Midway or from the programmers who did the home version. And then we also got to talk to other developers, like David Jaffe or Cliff Bleszinski, who played those games as fans. Mortal Kombat isn’t known for holding back – what doors did that open for them?

I think of it like a sandwich. The middle layer is what people would expect: the making of Mortal Kombat. Here are some John Tobias sketchbooks and an hour and a half of archival video. But at the bottom layer, you have this very human story about how Ed and John were an incredible creative force working together. What is it that made them work well together, and how did their relationship evolve over the years?

Then the highest level of the sandwich is how people saw video games differently after Mortal Kombat. People had this mental image of Mario, Pac-Man, or Space Invaders, so suddenly to walk into an arcade and see sprites doing over-the-top martial arts with blood spurting everywhere, because it was funny to the developers… that shifted how society saw video games, and that was part of the story we wanted to tell, too.

How do you gauge the success of something like the Mortal Kombat Legacy Kollection? On the business side of things, how do you ensure this is something you can keep doing?

Kohler: I believe it was Brian Eno talking about the album The Velvet Underground & Nico. He said something to the effect that the album only sold 5000 copies, but everybody who bought it started a band. I definitely want to sell more than 5000 copies of our games, but I think that we are, with some of the smaller projects that led up to this, laying the groundwork for a rethink of how this all works.

We are scaling up with a lot of very smart, targeted hires. We don’t want to bloat, but we do need to scale up, because off the success of the Gold Master series, and the realization that there’s a new way of approaching these products, we are actually getting a lot more people talking to us and wanting to work together. That means more projects happening simultaneously. And I think that you can measure success sometimes in a second-hand way, or second-level effects. Come back to us in a couple of years, and we’ll see how that’s evolved.

Frost: Obviously, it’s a business and we need to sell, but there’s an intrinsic value in situations where, like the release of Atari 50, over time we’ve added more DLC. We’ve gotten a lot of people DMing us and emailing us saying, “I didn’t grow up playing Atari games, I’m too young. But the presentation and story that you told really got me interested.”

I’m sure there are a large number of people who’ve seen the trailers for the Legacy Kollection and just think it’s a collection of games. Whereas, we view having the game up and running as the entrance to the club. That’s to get in the door. And a lot of companies don’t necessarily get past that, but we view it as the first step, and then build so much more upon that. It’s the challenge of getting the world out there and more people seeing it.

I measure success as this large influx of new people who might not have seen a Digital Eclipse product before, and are being introduced to it through an IP like Mortal Kombat or Turtles. And growing our fan and interest base organically. Someone who might have come in through Mortal Kombat may now say, you know what, I really liked how this was presented in the story – I’m going to look for other Digital Eclipse games. Versus, just saying I’m going to look for the next Mortal Kombat game.