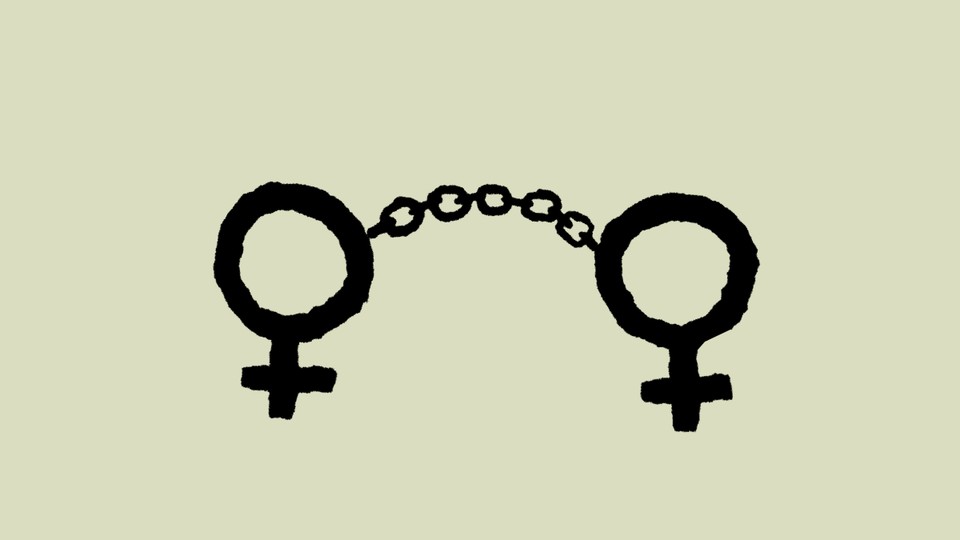

Before last week, women attempting to have their pregnancies terminated in states hostile to abortion rights already faced a litany of obstacles: lengthy drives, waiting periods, mandated counseling, throngs of volatile protesters. Now they face a new reality. Although much is still unknown about how abortion bans will be enforced, we have arrived at a time when abortions—and even other pregnancy losses—might be investigated as potential crimes. In many states across post-Roe America, expect to see women treated like criminals.

On Friday, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, ending abortion as a constitutional right. Nearly half of U.S. states either are in the process of implementing trigger bans—which were set up to outlaw abortions quickly after Roe was overturned—or seem likely to soon severely curtail abortion access. Reproductive-rights experts told me that in the near future, they expect to see more criminal investigations and arrests of women who induce their own abortions, as well as those who lose pregnancies through miscarriage and stillbirth.

Women have been criminally investigated for self-inducing abortions in the past, albeit infrequently. Prosecutors could draw on a variety of existing ambiguous laws that criminalize harm to a fetus, child abuse, concealment of a birth, abuse of a corpse, and practicing medicine without a license. (One report, published in 2018, estimated that prosecutors could use about 40 different types of laws to charge women who self-induce abortions and those who help them.) Without Roe, certain prosecutors may feel more emboldened to use them.

The end of Roe may also motivate states to pass new laws explicitly turning women seeking abortions into criminals. In an environment where abortion is illegal—and equated with murder by some—any pregnancy loss may be surrounded by suspicion and fear. Imagine a scenario where a nosy neighbor notices that the woman down the street used to be pregnant but is no more, or gets wind that an abortion might have taken place. If the neighbor calls the police and makes a report, depending on the local jurisdiction—and so much of this will be up to law enforcement’s discretion—an investigation may be launched. And the woman, who may still be recovering from an abortion or a miscarriage, may be subject to invasive physical examinations and humiliating interrogations. Her DNA may be taken. Every decision she made about her pregnant body might be turned into evidence.

Historically, the U.S. has not typically prosecuted women for having illegal abortions. In the roughly 100-year period before Roe v. Wade when abortion was largely outlawed, criminal investigations mainly targeted doctors who performed abortions. As Leslie Reagan, a history professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, wrote in When Abortion Was a Crime, “The penalties imposed upon women for having illegal abortions were not fines or jail sentences, but humiliating interrogation … and public exposure of their abortions.”

[Read: When abortion was a crime]

But in the years since Roe v. Wade, the legal landscape has changed. More and more, the U.S. has punished women for actions that may be perceived as endangering their pregnancies. “The blueprint already exists to bring these cases,” Dana Sussman, the acting executive director of the National Advocates for Pregnant Women, told me. In the past few decades, the fetal-personhood movement—which advocates the idea that a fetus has the same rights as a person already born—has gained a foothold in certain state legislatures. Many have passed laws recognizing fetuses as potential crime victims. About 38 states have feticide statutes, which criminalize killing a fetus. These laws, ostensibly written to protect pregnant women from violence by others, were passed as part of a strategic campaign by anti-abortion activists. Many feticide laws currently make exceptions for a woman getting a legal abortion; in some states with newly enacted abortion bans, Sussman predicted that the exemption would likely disappear. “Even with what we consider quite explicit language around not using those laws to prosecute pregnant women, they are used with some regularity against pregnant women already,” she said.

For instance, the National Advocates for Pregnant Women has tracked more than 1,700 cases from 1973 to 2020 in which individuals were investigated, arrested, otherwise detained, or forced to undergo medical intervention by the state for actions that were interpreted as harmful to their own pregnancies. Those cases included allegedly intentionally falling down the stairs (which the woman denied; the state never pressed charges), using drugs, and attempting suicide. Dozens involve women who self-induced abortions, though the exact number is still being tallied, a spokesperson for the organization told me.

The reproductive-health-rights advocacy group If/When/How has identified dozens of people who were “criminally investigated, arrested, or convicted for allegedly ending their own pregnancy or helping someone else do so” from 2000 to 2020. In 2015, an Indiana woman was convicted of feticide and felony child neglect after self-inducing an abortion. Her conviction was later overturned and replaced with a lower child-neglect charge. More recently, in April, another woman was arrested and charged with murder after Texas authorities said she caused “the death of an individual by self-induced abortion.” The charges were quickly dropped.

Many of these cases involve overzealous prosecutors contorting laws beyond their legislative intent, Farah Diaz-Tello, a senior counsel and legal director of If/When/How, told me. In the majority of cases, the charges are dropped or convictions overturned by higher courts—but not before causing real harm to the person accused. Women in these situations find themselves subject to invasive questioning by authorities, their bodies treated like evidence, their mugshots aired on local news. Diaz-Tello told me about one California woman who unexpectedly lost her wanted pregnancy. She and her husband wished to have a cremation for the fetal remains, but the funeral home said they needed a death certificate, so her husband reached out to the local coroner for help. The coroner told her husband to contact the police, who began an investigation. “She had this humiliating incident of police digging through her home,” Diaz-Tello said. "That traumatized her."

The growing willingness of prosecutors to go after individual women is testament to the success of the anti-abortion movement’s bid to promote fetal rights. It also mirrors a shift in tactics among an extreme segment of anti-abortion activists. Historically, the anti-abortion establishment had opposed prosecuting women, believing it to be politically unpopular, Mary Ziegler, a legal historian who has published several books about abortion, told me. (Ziegler has also written on the subject for The Atlantic.) “Starting in the ’80s and ’90s, folks in the anti-abortion movement realized that many Americans thought the movement was misogynistic or anti-woman,” she said. Directly advocating to punish women would only further entrench that belief. Instead, the mainstream anti-abortion movement framed itself as working to protect women from harm, portraying women seeking abortions as victims rather than criminals.

But in recent years, the movement has seen a growing debate over strategy. If abortion is believed to be murder, as many groups allege, why would a woman who terminated her pregnancy be exempt from punishment? The “abortion abolitionists,” a fringe offshoot that believes women who have illegal abortions should face murder charges, have recently gained more organizing power, Ziegler said. This group is behind a Louisiana bill that would have classified abortion as a homicide and allowed prosecutors to criminally charge women who have the procedure. (The bill was gutted following a public outcry, and those provisions were removed.)

“The anti-abortion movement is more extreme now. And I don’t think they’re going to stop at prosecuting providers,” David Cohen, a professor at Drexel University’s Kline School of Law, told me. The advent of self-managed abortion through pills makes it more likely that abortion seekers will be prosecuted, he added, because there is no one else to punish. These days, more than half of all U.S. abortions are done using medication abortion, a two-drug regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol approved by the FDA for pregnancies up to 10 weeks. The first drug, mifepristone, prevents the pregnancy from progressing. The second drug, misoprostol, is taken 24 to 48 hours later and works to empty the uterus by causing cramping and bleeding. “It’s hard to police the providers who are sending those pills or the pharmacies that are sending those pills, because they might be overseas or in another state,” he said. Low-income women, women of color, and other marginalized people—who already experience more surveillance by the state—will face a higher risk of arrests and prosecutions, he said. “We are going to see a lot of suffering based on race, based on poverty, just like we see with the criminal-justice system now.”

[Read: When a right becomes a privilege]

The criminalization of abortion is also likely to damage the relationship between women and their health-care providers. Miscarriages and self-induced abortions using medication typically look clinically indistinguishable. Women who require medical care after any sort of pregnancy loss may hesitate before going to the hospital for fear of legal repercussions. “It’s not going to be the world of back-alley abortions,” Sonia Suter, a professor at George Washington University Law School, told me. “But we will have bad outcomes in these other ways where people are not getting the care that they need.”

Losing the constitutionally protected right to abortion will result in women being forced to bear children they do not want, drastically changing the course of their lives. But the repercussions of overturning Roe go beyond abortion; the Supreme Court’s decision is also about how much government control and surveillance can be exercised over a person. In places where abortion is illegal, a woman’s body could become a common site of state investigations: analyzed coldly, mined like a crime scene, exposed to authorities, and, fundamentally, not her own.