Baseball has been offering a vexing question to small-market clubs for decades.

In a sport with the wealth gap widening by the year due to local TV deals among other franchise-specific financial streams, how do teams on a tight budget consistently compete?

This is something the Milwaukee Brewers attempt to answer every year.

It turns out the best answer might prove to be almost 2,000 miles away in the Dominican Republic.

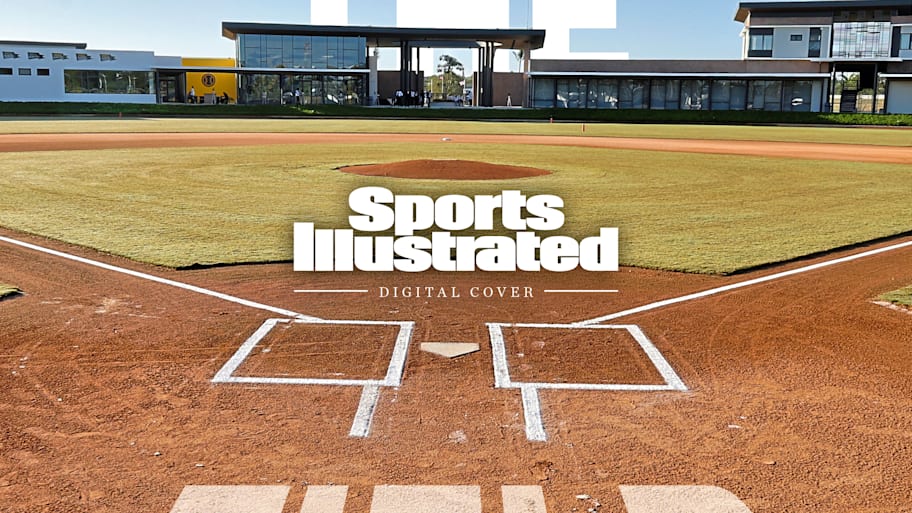

In 2017, MLB hard-capped international spending, giving every team a chance to find top-tier talent without needing to have deep pockets in free agency or by going on a decade-long tanking mission to earn top picks in the MLB draft. A year later, Milwaukee bought 30 ½ acres in Santo Domingo Este to eventually open a state-of-the-art facility while concurrently spending $60 million in 2018 under owner Mark Attanasio to renovate their Arizona spring training facility.

The Dominican dream was completed for more than $20 million last year on a 1.3 million-square foot academy. It’s able to house 106 players between 22 dorm rooms and three tryout player rooms. Overall, there are four structures for the academy including a dorm, clubhouse, kitchen and administration building. Inside the clubhouse, a 3,400-square foot gym can be found, five times the size of what it was in the previous facility. Finally, there are two classrooms to help players both complete high school and learn English.

“I’m very appreciative of what the Milwaukee Brewers have done for Latin American players, myself and other Latins that they have,” says star outfielder and native Venezuelan Jackson Chourio. “I think what they do is give us an opportunity to play and do a good job of opening the door for us and giving us that opportunity. The truth is that complex down in the Dominican Republic is awesome. It’s beautiful. When I was down there, it wasn’t quite the same. I’ve gotten the chance to go down there and it’s incredible.”

Every MLB team has an academy in the Dominican Republic, a baseball hotbed that contributes the most players to the major leagues outside of the U.S. But their new crown jewel should help the Brewers attract top talent in Latin America, helping them to continue a streak of success highlighted by six playoff appearances over the past seven years, including four National League Central titles and a 2018 trip to the NL championship series.

“It’s not even close. It’s not even close,” says Brewers starting pitcher Freddy Peralta, comparing the current facility to the previous one. “I remember last offseason I stopped by and it was crazy. I was in shock. I was surprised at how everything looks there. The kitchen is huge. The weight room, the fields, everything. It’s an unbelievable place. I told them to do whatever you need to do to these guys and let them know there’s another level because they probably don’t want to come out of here. This is a beautiful place.”

Chourio came along before the new facility opened, but symbolizes the organization’s commitment to scouting in Latin America.

In January 2021, the Brewers signed the 16-year-old Chourio using their international pool money, along with a $1.9 million signing bonus, the biggest bonus in franchise history for an international prospect.

Once in Milwaukee’s system, Chourio became a baseball comet. He began in the Dominican Summer League and Venezuelan Winter League before going to High-A in 2022, finishing that season with six games at Double-A Biloxi. The next year, Chourio dominated the circuit, slashing .280/.336/.467 with 22 home runs, 89 RBI and 43 stolen bases across 122 games.

Then, before the 2024 season, Milwaukee general manager Matt Arnold did something the Brewers had never done before. He bought out Chourio’s arbitration years before the prospect ever stepped onto the grass at American Family Field, giving him $82 million over eight years.

And while Choruio isn’t the first player to ever sign a long-term deal with a MLB team prior to his first at-bat, his entire journey could be a template to be followed.

“I think it’s certainly something we’re open to and we want to make sure we’re making bets on the right players and the right people first and foremost,” says Arnold of the Chourio-type extension. “… With Jackson, we felt like we had all those ingredients in place and obviously, there’s some real risk when you make those kinds of bets. But when you’re talking about the right kind of person, we’re always open to those kinds of agreements with our younger players.”

To that point, there are a few Latin players new to Milwaukee’s system who could see a similar trajectory.

A year ago, the Brewers landed a tremendous international haul, signing infielder Jesús Made (ranked No. 1 among Brewers prospects by MLB Pipeline) and shortstop Luis Peña (No. 5) before putting them into the Dominican facility. Both of them are now in Low A with the Carolina Mudcats and producing.

Made, who just turned 18 last month, is slashing .280/.389/.423 with 16 extra-base hits, including four home runs, and 23 stolen bases in 47 games. Peña, also 18, has been even better with a .319/.378/.522 line and 15 extra-base hits alongside 24 swiped bags in just 35 games (a concussion briefly sidelined him in May). Perhaps most encouraging is that in 156 plate appearances, Peña has struck out just 18 times, a remarkably low rate for a player who would’ve just graduated high school if he grew up in the U.S.

“The similarities are that [Made, Peña and Chourio] stand out immediately,” says Carolina manager Nick Stanley. “All three of those guys, as soon as you see them do anything, take a swing, run down the first base line, you say, Oh, that’s a little bit different. I think all three of them are really focused on their careers and want to be great. I saw Jackson as a 19-year-old all year in Double A in 2023, and it was clear he wanted to be a great Major League player. I’m seeing some of those same things out of Made and Peña right now.”

At spring training, Milwaukee made sure to get the pair stateside to spend some time around the parent club. While neither came close to taking an at bat or anything of that nature, the visit was fruitful as some of the top-line prospects got to spend time with some of the Brewers’ big-league stars.

Speaking with Peralta, the 29-year-old talked about that moment as a time to impart wisdom on how to create and refine their routines while learning what makes their respective games work well and using preparation to their advantage.

“One of the big things that we made sure to try to do as much as possible was bring those young Latin players over to Major League camp and get that experience,” Arnold says. “Even if they weren’t in big-league camp, they would come over for the day or they’d stretch in the morning with us and make sure they were around for batting practice. Maybe they weren’t in the game but they’d spend the day in the dugout. Having that experience in major league camp, not signed that long ago … we think that’s extremely valuable, especially in that environment.”

For the Brewers, finding and developing Latin talent isn’t just about baseball. It’s about succeeding in the margins, something the organization knows all about in a variety of areas.

Currently sporting MLB’s 24th-ranked payroll at $108 million, trailing the Colorado Rockies, Cincinnati Reds and Washington Nationals, Arnold and his staff can’t afford misses on priority draft choices and international signings like big-money clubs can.

Milwaukee has done well with domestic scouting, showcased by recent first-round picks in second baseman Brice Turang and outfielders Garrett Mitchell and Sal Frelick, along with current top-100 prospects in infielder Cooper Pratt and pitcher Jacob Misiorowski—the latter of which was called up to the majors on Tuesday. Yet the ability to cultivate Latin players through multiple levels of the minors, and across multiple continents, is becoming a separator.

“That’s really where we need to be successful,” says Arnold of helping young talents. “We have to be able to develop our own players here and that starts in the draft, that starts internationally and then having that pipeline with player development really work very cleanly together in a way that we can develop homegrown talent here from Milwaukee. It’s going to be harder to access [talent] on the major league market.”

While Peña and Made are the young hotshots from last year’s international class, the Brewers have another top prospect in catcher Jeferson Quero, a 2019 signing from Venezuela. The 22-year-old backstop returned to Triple A just last week from a torn labrum that sidelined him for all of ‘24, requiring a dozen staples in his throwing arm. Still, the 2023 minor league Gold Glove winner projects as a top-end catcher if he regains his form.

According to Baseball America's May rankings of the Top 100 prospects in baseball, 20 are international signings. And of that subset, only three teams have multiple players from that group, including the Seattle Mariners (four), Cleveland Guardians (two) and Brewers (three).

Made is the highest ranked of any international player, ranking sixth. Quero checks in at 66th, while Peña debuted on the list at 79th.

Although talent will always reign supreme, Milwaukee is investing in the people as much as the players. The Brewers have made it essential to help players, especially foreign-born ones, find housing closer to the ballpark while also helping them learn English.

“What can be a big issue is small things that have nothing to do with baseball,” Stanley says. “They can create a little bit of anxiety and we do everything we can to eliminate that. The language barrier, just day-to-day life, can cause some stress. Not being familiar with the culture, the language, it can sometimes spill over onto the field. We try to get them to the point where they are comfortable to be themselves, they have the help they need. They’re in English class if they need it, we provide that. That way, when it comes to playing baseball, they’re just playing baseball.”

This isn’t only true in the minor-league levels. Just ask Chourio.

As a rookie, Chourio had the burden of massive expectations between being one of the top-ranked prospects in baseball and his $82 million contract. Through June 7, Chourio was struggling mightily, hitting .209/.251/.337 with six home runs, seven stolen bases, 10 walks and 50 strikeouts through 53 games.

Instead of sending him down, Arnold stayed the course, buoyed by internal support such as field coach Néston Corredor and assistant coach Daniel de Mondesert. More importantly, though, were the fellow Latin players including shortstop Willy Adames, catcher William Contreras and Peralta, who mentored the young Venezuelan through a tough stretch.

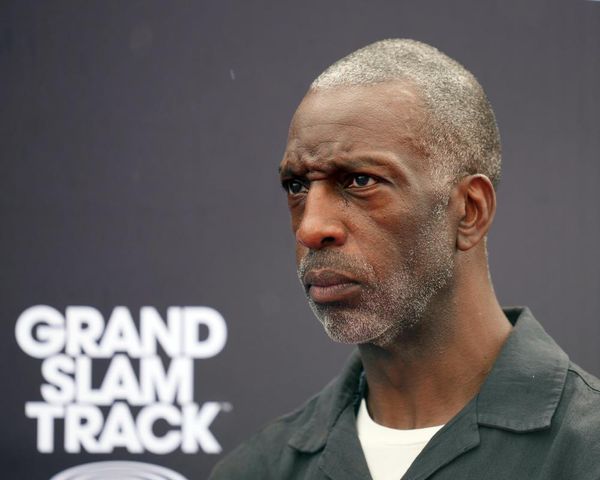

“The guy who took him under his wing was Freddy Peralta,” Arnold says. “To have that kind of mentor who has been through it, who has come up from nothing in the Dominican Republic, to have a guy like that who’s had success at the highest level, put your arm around you and say Hey, you’re going to be okay, kid, and believe in you is so important. Having those experienced Latin players for the young guys is super important.”

“It’s hard to even describe,” says Chourio of Peralta’s friendship. “He’s just such an incredible person, and we’ve had many good conversations together. He’s a guy that every time he goes out there and takes the mound, I feel pretty comfortable and I’m happy to see him whenever he’s out there. Just in all aspects, he’s been an incredible person that I’m extremely appreciative of.”

Peralta has taken to having all the Latin players (others are invited as well) over to his house for a cookout on off days and most afternoons following a day game at home. The food ranges from ribeyes and chicken wings to pork ribs and churrasco, all washed down with a glass of wine. Red wine, to be exact.

“It’s about making people feel comfortable,” Peralta said. “Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. That’s what I told him. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. You’re here because you deserve to be here. You earned the opportunity to be here. You got paid without playing one game here. That means you’re great. You’re ready for the game.”

For Peralta, the opportunity to help Chourio wasn’t an organizational obligation, but one he felt personally. Having come to Milwaukee in 2018, Peralta didn’t feel quite the same level of mentorship from the Latin veterans.

When Chourio was promoted and subsequently went through the typical rookie struggles as a very atypical first-year player, Peralta looked to provide bedrock.

“My parents and people around me taught me that we have to help each other whenever we have the opportunity,” Peralta says. “When I saw him coming up, I remember I saw a very, very talented guy. We all knew that when we came here, we needed some help from people that were around. I had some help when I came here, and I felt that’s what I had to do in the moment. Willy and I, we spent some time with him trying to help him more mentally than whatever he had to do on the field because we knew he was able to do everything.”

Chourio has since proven Peralta right. He torched pitchers throughout the back half of his rookie season to hit .275 with 21 home runs and 22 stolen bases on the season while finishing third in NL Rookie of the Year voting behind Pittsburgh Pirates ace Paul Skenes and San Diego Padres center fielder Jackson Merrill. In the three-game wild-card series against the New York Mets, Chourio was electrifying, smashing two homers while hitting .455. He’s comparatively endured a bit of a sophomore slump this season, but even still grades out as a league-average hitter with a .254/.280/.430 slash line and 10 homers in 66 games—quite an accomplishment for a 21-year-old. And as Chourio showed during last year’s stellar second half, the best is likely yet to come.

This century, small-market teams have usually watched the elites celebrate in October.

Only the Florida Marlins (2003), Kansas City Royals (2015) and Houston Astros (2017) have won the World Series this century while in the bottom half of league payroll, ranking 25th, 16th and 18th, respectively. Of the 25 champions in that span, 18 were in the top 12 spending-wise the year they won. And while the Oakland Athletics contended for years under general manager Billy Beane using a revolutionary “Moneyball” system and the Tampa Bay Rays reached two Fall Classics by modernizing those tactics, most clubs on a tight budget didn’t play past their 162nd game beyond a random year here and there.

The Brewers, despite all their resourcefulness, haven’t been able to reach the holy grail. Milwaukee has often been close in recent years, only to lose many times to teams with far higher payrolls, including the New York Mets last October.

If the Brewers and teams like them are ever going to not only be consistently respectable but actually win it all, the process likely needs to start with dominating on the even grounds of international scouting, where the big budgets in New York and Los Angeles can’t overwhelm the system.

“Market discrepancy is just something that never enters my mind,” Arnold said. “It’s something we recognize, that we’re probably going to be the underdog going into the day and we have no problem with that. I think it’s something we have to embrace and it’s something that we, as an organization, probably go about with a chip on our shoulder a little bit. We take pride in doing things the right way here and working hard and being a first-class organization.”

Small-market teams have long been trying to figure out how to compete in a sport slanted toward the wealthy. The answer might begin internationally, and end with what happens domestically.

More MLB on Sports Illustrated

This article was originally published on www.si.com as The Brewers’ Blueprint for Small-Market Success Lies in Latin America.