On the afternoon of the 2016 election, I took a cab directly from my polling place in South Brooklyn to JFK, where I boarded a full flight to San Francisco. In the evening, when the plane took off, the consensus seemed to be that by the time we landed, the country would have elected its first female president. I wasn’t sure, so when the miniature television that had been allotted to me came alive as we climbed to 10,000 feet, I turned it to the news.

As the sunset outpaced the plane and the dark rose outside our windows, I saw that everyone else had their television turned to the news, too. Pennsylvania and Ohio, Iowa and Nebraska, passed silently beneath us as the returns came in.

The flight from JFK to SFO is about six and a half hours, depending on the wind, so between the hours of 7 p.m. and midnight eastern on November 8, 2016, 180 televisions shone their bluish light on 180 faces arranged in rows of three, facing forward. No one spoke. Strapped in shoulder to shoulder in a metal tube hurtling 35,000 feet over the breadth of America, everyone watched the country’s electorate reveal itself on our own screens. By the time we landed, the decision had been made.

I mentioned this the next day to my mother when we spoke on the phone: the silent, dark plane; all the people quietly watching, hour after hour.

“That’s just like White Noise,” she said.

This is something my mother has been saying to me for about 15 years. White Noise is one of her seminal texts. She read it for a class after going back to graduate school to study literature when I was in my late teens, got excited about the book, and later taught it to her own students. “This is just like White Noise !” she would say, listening to the radio or sitting at the dinner table. She still does this a few times a year, but for a while she was finding White Noise echoes at least once a week.

I seem to be the only college-educated person left in America who hasn’t read Don DeLillo. Sometimes my mother will read something I’ve written and say, a little balefully, “You should really be reading White Noise,” suggesting that this gap in my education, specifically, is egregious and foolish. She’s probably right. Any writer with an interest in probing “American magic and dread”—to borrow a phrase from the novel—is probably in conversation with DeLillo, whether or not she knows it.

I have no good reason for how or why I evaded this book for so long. It never showed up on a high-school or college reading list, for one thing, but more pertinently I have an embarrassing and completely unproductive resistance to reading what people tell me I should read. I have still never cracked The Little Prince, or On the Road, or Slaughterhouse-Five. I know. The only person this is hurting is myself. And yet I avoided White Noise with special stubbornness. I had the vague sense that the book was a reflection on how alienating modern American life can be—a theme you hardly need to seek out in fiction. People kept referring to it as a masterpiece of postmodernism, which—after years of being assigned so many other books of that genre—didn’t light my fire. Really, I had no idea what it was about. When I asked my mother, she was cryptic. “You’ll just have to read it.” That’s just like my mother.

Sometimes my partner and I look up at each other while we’re doing chores or reading, or maybe when we articulate some minor thought at the same time, and smile and say, “Love.” It’s shorthand. We mean: This is what love is, how strange and funny and good.

Most of the time, my brain chimes a silent little chime after “Love.” It’s what makes a Subaru a Subaru.

This is just like White Noise. In fact, it’s a clear echo of a scene in White Noise. Jack Gladney, our protagonist—a professor at the College-on-the-Hill, a midsize liberal-arts college in Blacksmith, a midsize town somewhere in the midsection of the U.S.—is watching his daughter sleep and feeling the immanent swell, the “desperate piety,” that parents sometimes feel. The girl turns in her sleep and mutters something, propelling him to lean forward to catch her “language not quite of this world.”

I struggled to understand. I was convinced she was saying something, fitting together units of stable meaning. I watched her face, waited. Ten minutes passed. She uttered two clearly audible words, familiar and elusive at the same time, words that seemed to have a ritual meaning, part of a verbal spell or ecstatic chant. Toyota Celica … She was only repeating some TV voice.

Nevertheless, Jack thrills at his 9-year-old’s incantation of brand names, which, he notes, is “part of every child’s brain noise, the substatic regions too deep to probe. Whatever its source, the utterance struck me with the impact of a moment of splendid transcendence.”

Prodded by an editor at this publication, I finally read White Noise, a fact that vindicated and exasperated my mother in equal measure. The novel has been adapted by Noah Baumbach into a feature film starring Adam Driver and Greta Gerwig, despite a reputation for being unadaptable because of its density of detail and its fractured, occasionally absurdist plot. For the first time, nearly 40 years after the novel’s publication, Americans will consider White Noise on-screen, which is either the best or worst—but definitely the most ironic—medium for it.

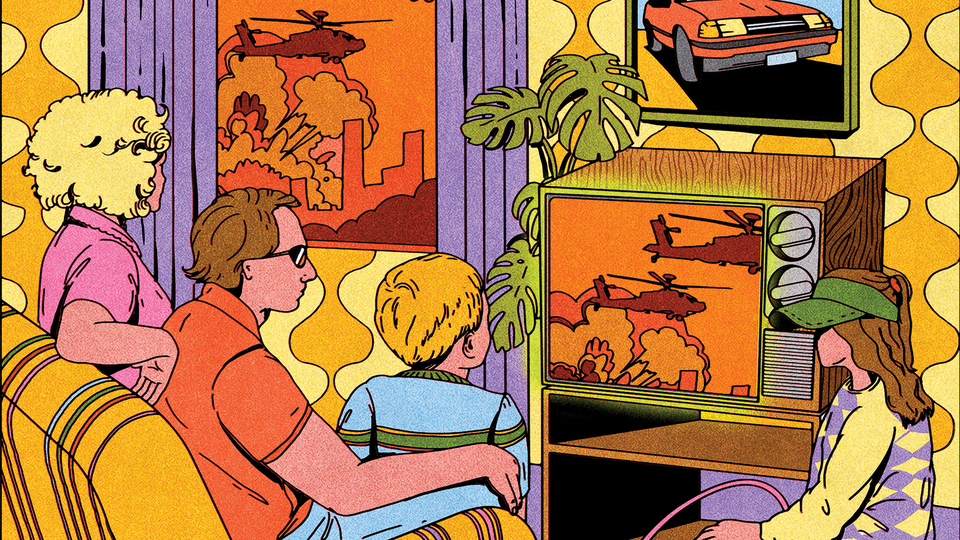

The television is always on in the house that Jack shares with his wife, Babette, a “fairly ample” woman with a blondish mop, and four of their children from various prior marriages. Fragments of programming intrude into every aspect of daily life. (“Now we will put the little feelers on the butterfly,” says the voice on the television, or “And other trends that could dramatically impact your portfolio.”) Every Friday, the family sits and watches together, sometimes a sitcom, sometimes a documentary—though far and away the biggest hits are the disasters, human and natural: car accidents, earthquakes, villages swallowed by a lava flow. “Every disaster made us wish for more, for something bigger, grander, more sweeping,” Jack notes. Vaguely disconcerted by this family-bonding exercise, he mentions it to a colleague, the chair of the “department of American environments,” who assures him that their behavior is totally normal. It’s practically a neurological imperative, he insists: “We’re suffering from brain fade. We need an occasional catastrophe to break up the incessant bombardment of information.”

The way that technology—and particularly the television screen—seeps into our consciousness is a primary subject in White Noise. “You have to open yourself to the data,” a visiting lecturer in American environments named Murray Jay Siskind tells Jack.

Look at the wealth of data concealed in the grid, in the bright packaging, the jingles, the slice-of-life commercials, the products hurtling out of darkness, the coded messages and endless repetitions, like chants, like mantras. “Coke is it, Coke is it, Coke is it.” The medium practically overflows with sacred formulas.

No part of the American mind remains untouched by branding. Nothing is sacred, and so eventually the branding itself comes to acquire an air of the sacrosanct. The grocery store becomes a temple. Reality is determined by the language and images that represent it on television, rather than the other way around.

Jack is renowned as the founder of an academic field, Hitler studies, though by his own admission he is not so much brilliant or pioneering as canny. He saw a niche and exploited it. Hitler studies is less concerned with history, politics, and the Second World War than with the dictator’s success at corralling and manipulating group fascination, his genius for turning himself into a figurehead. Jack is interested in the surface details of Hitler, his theatrics, his optics. He, too, adopts a uniform, never removing his sunglasses or his academic robes when on campus. He teaches “Advanced Nazism” and carries around a copy of Mein Kampf. He barely speaks any German, but this hasn’t really been a problem. Though he can’t read Mein Kampf in its original language, he likes the way German sounds, the way it seems to carry “an authority” that he can’t put his finger on. “Look at it this way,” he explains to his stepdaughter, Denise. “Some people carry a gun. Some people put on a uniform and feel bigger, stronger, safer. It’s in this area that my obsessions dwell.”

I was caught off guard by this: Although the book takes American alienation, decadence, and moral decay as its subject, it’s profoundly funny. Baumbach has preserved the humor in his adaptation, along with the foreboding backdrop. The rhythm of his dialogue—everyone talking over and past one another in rapid-fire torrents of impressive but usually counterfactual or irrational language—is so perfectly chaotic, nearly slapstick, that the audience at the press screening of White Noise the morning of its premiere at the New York Film Festival erupted in laughter. Baumbach’s Jack is equally hilarious and pathetic thanks to Driver’s exquisite deadpan, his commitment to the bit (though he’s too young to play Jack by about a decade, and Gerwig is too young for her role as well).

The production design is funny in its own way: The grocery store gleams, almost menacingly gorgeous. Everything is very ’80s—the jogging suits, the Hula-Hoops; Gerwig’s wig is a kind of joke all by itself. This hyper-saturated, highly stylized theatrical approach accents the story’s humor and presages the moments when the film’s mood and color palette switch to something more like noir. In the dark, Jack has nightmares; we learn that placid Babette is secretly tortured by the fear of death even when life seems like the suburban middle-class dream, a “condition” for which she takes mysterious pills. Every register contains a deft, satisfying touch of the hysterical.

and pathetic. (Wilson Webb / Netflix)

I wonder if laughing at White Noise feels different than it used to. The novel skewers Americans’ dependence on technology and screens, a phenomenon that is incalculably more intense than it was in 1985. The protagonist may have seemed like a more absurdist construction back then: the paunchy white American male of middling intelligence who idolizes dictators and never turns off the television—who studies and exploits the shortcut to power found in putting on a good show, regardless of whether you have any idea what you’re talking about. Jack is funny because he’s a relatively harmless fool—a product of his circumstances rather than their author; an American patsy. Terrified to die, he idolizes Hitler because Hitler seems “larger than death.” Jack has no meaningful power, really, so he’s a tragicomic figure. Or he was.

I texted my mom to ask whether she found White Noise funny when she first read it, during the early years of the Iraq War. “Not very,” she replied.

Critics have been calling DeLillo’s work prophetic nearly his whole career. When the novelist Jayne Anne Phillips reviewed White Noise in 1985 in The New York Times, she noted that the plotline was “timely and frightening.” The reason Phillips gave was that the middle section of the novel revolves around an “airborne toxic event.” (This is what the authorities on the radio agree to call it, having tried and discarded “feathery plume” and “black billowing cloud.”) Something lethal has been released into the air. Without warning, Jack and his family are living through a public-health disaster. A month before the book appeared, an industrial accident in India had killed thousands of people; it seemed DeLillo had almost foretold the disaster.

Obviously, this plotline remains eerily prescient. Like our own recent airborne toxic event, the poison in White Noise is ambient, diffuse, unpredictable. It upends everyone’s lives, even those who think themselves economically immune to “disasters.” (Disasters happen elsewhere, Jack is sure. “Did you ever see a college professor rowing a boat down his own street in one of those TV floods?”) The symptoms it supposedly causes change by the hour—the authorities can’t really get a handle on it, and mass hypochondria shifts every time there’s an update. Jack reassures Babette that something is doubtless available to deal with such a thing, probably a squad of “custom-made organisms” ready to eat the toxic cloud. Babette feels awe—“There is just no end of surprise”—but also fear at this prospect. “Every advance is worse than the one before because it makes me more scared,” she says.

“Scared of what?”

“The sky, the earth, I don’t know.”

Jack agrees. “The greater the scientific advance, the more primitive the fear.”

Even aside from the airborne toxic event, calamity is ambient. Children are evacuated from school with no clear reason given, only the suspicion that the environment is somehow dangerous. Children participate in emergency evacuation drills where they lie in the street, playing victim. Lev Grossman, writing about the book for Time in 2010, suggested that it was “pitched at a level of absurdity slightly above that of real life,” a statement that more than a decade later no longer feels quite true.

We are always running from a disaster we ourselves have caused, it would seem. We are always alienated. Americans are perpetually spiritually blotted by consumerism and afraid to die. Fitbits. #Sponcon. “Likes.” “Alternative facts.” Infinite scroll. Amazon same-day delivery. When my grandmother was dying, I watched on my cellphone as a priest performed her last rites; I was sitting on the floor of an empty apartment 2,000 miles away. Not knowing what else to do, I took screenshots of her face, impassive. When the call ended, I didn’t see her again, except now my phone occasionally delivers me the screenshots in the middle of the day as “Memories.”

I put out a call before I began reading White Noise, blank slate that I was, for general impressions, and the majority of people who wrote back said that they had read the book in college. Some liked it, a few objected to the characterization of Babette—who, through Jack’s eyes, is more of an instrument than an interiority—but most remembered it favorably, if vaguely. I started to understand why this book appears so often in classrooms, why teachers choose to teach it. It’s a masterpiece of postmodernism, sure. But what White Noise does well—and what literature teachers are often in the position of training students to do—is render visible (or audible, if we want to follow DeLillo’s metaphor) aspects of social and political life that have been normalized into near invisibility.

One’s culture is largely composed of what can no longer be explicitly sensed—we often fail to notice what’s endemic in our social world, believing it to be the given state of things. Intrusions of the uncanny signal that culture is changing faster than our ability to absorb the results into our conception of what’s normal. We live in an uncanny time—though there has been no moment in my life, at least, that has not seemed to be an uneasy, unnatural moment in American life. White Noise was originally published against the backdrop of the Cold War; nuclear anxieties; the reelection of Ronald Reagan, an entertainment personality, to the office of the president. It turned 10 as the AIDS epidemic in the U.S. began to wane, as personal computers began appearing in American homes, nudged into daily life by the advent of the internet. It turned 20 as the War on Terror was truly getting under way. It is turning 38 as it becomes a movie that will be available for streaming, via Netflix, into tens of millions of American homes through televisions, tablets, and phones that also track how many minutes of the night you dream.

Things still seem to be just like White Noise because of DeLillo’s gift for observing the world as if he had just been dropped into it. Instead of simply opening some gum, Babette pulls “the little cellophane ribbon on a bonus pack of sixteen individually wrapped units of chewing gum.” This gaze is evident in his many subsequent novels, most recently The Silence in 2020, a pandemic-related novel that he happened to finish just before COVID-19 made itself known. He credits this vantage to having been raised by Italian immigrants in the Bronx, and to having “roots elsewhere. We are looking in from the outside.”

In a recent interview with DeLillo in The New York Times Magazine, David Marchese cited the cultural theorist Raymond Williams, who posited that every era has “a structure of feeling, which is basically the way that people experience the times in which they live.” DeLillo had not read Williams, but Marchese’s reference still felt correct. In White Noise, DeLillo nailed a structure of feeling that shapes our present consciousness. Writing shortly after September 11 for Harper’s Magazine, DeLillo articulated it this way: “We don’t have to depend on God or the prophets or other astonishments. We are the astonishment. The miracle is what we ourselves produce, the systems and networks that change the way we live and think.”

When I called my mother to tell her I’d finally read the book and wanted to talk about it, we agreed to do a sort of book club on Zoom. She logged on from home, but I couldn’t see the room behind her: She had programmed a branded image from an organization she works for as her “background.” When she tried to show me her copy of White Noise (a repurchase; she lost her original, dog-eared copy crammed with notes many years ago, and still resents this now-decade-old replacement), it flashed visible and invisible, interfering with the Zoom setting.

“Turn off your weird background,” I said. “I can’t see anything.”

She smiled and cocked an eyebrow. “Are you sure? How about this one?” The beach I grew up playing on appeared behind her. “How about this one?” She was in the mountains. “How about this one?” The desert. “This one?”

She was excited to have looked over the book again for the first time in a few years. “I can’t believe how funny it is! I took it so seriously when I first read it.” Then again, she’d always been receptive to skepticism about technology and mass media. “Remember I didn’t let you and your brother watch TV?”

“I remember. The book really was funny. He’s a Hitler professor who can’t even speak German?”

“Hilarious.”

We chatted for an hour or so. She pointed to the echoes between Jack and Donald Trump. I wanted to know what reading it for the first time had felt like. She called me a few weeks later, after I’d been texting her about White Noise again. “I’ve been thinking more about that question you asked me, about whether I found the book funny when I read it the first time,” she said.

“Tell me,” I said.

“I think when the book first came out, and even when I first read it, we weren’t so used to seeing the posture of dry, overweening wit, or of irony, as comedy.” It was always clear that the book was humorous, she suggested, but the gesture of laughing out loud at jokes told about the sinking ship as it goes down is more recent. We are primed to laugh at black humor now, she said, and black humor becomes funnier, somehow, the blacker—or bleaker—things get. She mentioned rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

It so happened that when she called, I was reading a new book by the choreographer Annie-B Parson, The Choreography of Everyday Life. She observes, “I think it was Kundera who wrote that the definition of irony is one eye crying and the other eye watching that tear fall.” This ability to hold our tears at a distance—whether they’re tears of laughter or not—is something Americans have gotten very good at.

My mother will like the movie, I think. Especially the credits, which involve an elaborate dance sequence, zany and extravagant, set to the sounds of the first new LCD Soundsystem track in years. Baumbach loves credits at the end of movies. He likes to watch them all the way through, and he wants his audiences to as well. The dancing is his way of helping us over the finish line: He knows that Americans love a vacuous but well-executed spectacle.

This article appears in the January/February 2023 print edition with the headline “White Noise Used to Be Satire.”