In Ukrainian dictionaries, the word “surzhyk” originally referred to a mix of grains – rye, wheat, barley and oats – or to flour made from a blend of these that was considered of lower quality. But its meaning morphed to mean a mixed or “impure” language – and today it refers to a blend of Ukrainian and Russian used by millions in Ukraine.

Often stigmatised in the past as a marker of rural backwardness, poor education or simply ignorance of Ukraine’s literary norms, the status of the Surzhyk language is now being reconsidered in wartime – not as a threat to Ukrainian identity, but as a way for native Russian speakers to communicate in a way that is more socially acceptable in a country at war with Russia.

Since the full-scale invasion of 2022, people in some central and eastern areas of Ukraine who might have primarily spoken Russian have been switching to Ukrainian, particularly in public. These are people who would have understood and occasionally used Surzhyk, but would have seen it as a form of Ukrainian “pidgin” – not to be used in formal situations. But now, it’s increasingly being used and any stigma that might have attached to it is slowly disappearing.

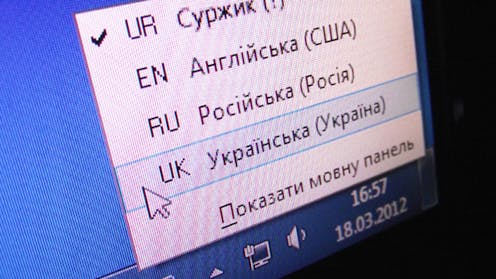

There has been debate about whether it’s a language in its own right, or a dialect or even slang. Most Ukrainian linguists tend to refer to it in English as an “idiom”. But it’s important to note that Surzhyk varies by region and is constantly evolving.

In the 1930s, it was heavily Russianised, reflecting Soviet language policies. More recently, after decades of Ukrainian revival, it has tilted in the other direction towards Ukrainian. And other influences are creeping in, especially from English. Words like “булінг” (buling, like the English “bullying”) and “донатити” (donatyty, meaning “to donate”) are slipping into everyday speech, showing how Surzhyk mirrors society’s shifting horizons.

But it is also a product of trauma and necessity. As Ukrainian writer Larissa Nitsoy notes, Ukrainians survived genocide – and they also survived linguicide. During the Soviet era, Russia made strenuous efforts to eradicate the Ukrainian language, punishing – often executing – those who spoke, wrote and taught in Ukrainian. To survive, they adapted.

Later, Surzhyk continued as a practical tool of social mobility. As Ukrainian-speaking villagers moved to Russian-dominated big cities in Ukraine for work or education, they adopted a hybrid idiom to “pass” as local. Laada Bilaniuk, a US-based anthropologist, calls this “urbanised-peasant Surzhyk” – a way of mimicking Russian without abandoning one’s Ukrainian linguistic roots.

In this sense, Surzhyk was both a survival strategy under Russian colonial rule, and an adaptation to urbanisation.

How widespread is Surzhyk?

In 2003, the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) estimated between 11% and 18% of Ukrainians spoke or wrote in Surzhyk – roughly one in seven people at the time. A more recent study of 104 students of the National Transport University in Kyiv in 2024 found that more than half of respondents (51%) admitted using some form of Surzhyk at home, and nearly one in five used it in messages with friends. Admittedly, the 2024 study was done on a much smaller scale, but the contrast is striking.

The question is: has the proportion of Surzhyk speakers really increased significantly – or simply the willingness to admit using it? Could it be that shame is giving way to recognition of Surzhyk as an acceptable tool for communication?

For decades, Surzhyk was a source of embarrassment. Nitsoy was voicing widespread Ukrainian nationalist views when she described it in 2021 as “a rape of the Ukrainian language by Russian”. Pavlo Hrytsenko, director of the Institute of the Ukrainian Language, argued that speaking Surzhyk signalled personal “underdevelopment”, a refusal to master the country’s literary language. Others were even more blunt, suggesting that: “By speaking Surzhyk, we humiliate ourselves.”

The assumption was that Surzhyk speakers leaned lazily toward Russian rather than making the effort to learn proper Ukrainian. These attitudes produced active campaigns to “correct” it, like the 2020 chatbot StopSurzhyk, which suggested literary alternatives for “improper” words.

This stigma was reinforced by the proportion of Ukrainian-Russian words and phrases that make up Surzhyk. Throughout the 20th century, Surzhyk was heavily Russianised, reflecting the dominance of Russian in public life. But more recently, and especially in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the balance has shifted. Surzhyk now carries more Ukrainian elements and has been increasingly viewed not as a regression, but a reversal.

A bridge for Russian speakers to Ukrainian

Today, Surzhyk is generally seen by Ukrainian scholars, writers and the wider public as transitional, even useful, and is often used by Russian speakers switching to Ukrainian.

Ukrainian linguistics experts argue that mocking or judging those speaking Surzhyk is misguided, because every language learner passes through such a stage, and that any Surzhyk is better than Russian.

Philologist Svitlana Kovtiukh likens the language to “slippers at home” – meaning that one might wear formal shoes in public but slip into something more comfortable in private. Ukrainians should be encouraged, according to Kovtiukh, to speak literary Ukrainian in official settings – as required by the Language Law – but be free to use Surzhyk in their personal life. What Soviet authorities once dismissed as “weeds” in the national language may actually be the streams that nourish it.

This reversal of perspective reflects a new hierarchy. Once a way for Ukrainian speakers to survive in a Russian-dominated world, Surzhyk is now a way back to Ukrainian for Russian speakers to Ukraine’s national language.

Once abominated by Ukrainians, it is increasingly seen as a tool of linguistic decolonisation. It’s both a practical way for Russian speakers to understand and be understood in Ukraine, and an alternative to what most Ukrainians see as the language of their oppressors.

Oleksandra Osypenko does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.