A few days ago I walked into a well-known department store on Oxford Street. When I looked up from the bottom of the escalators, I saw a number of posters on the fourth floor. Being shortsighted, I could not tell exactly what each poster was but I was certain that one of the portraits, a solemn man in a black suit, was Atatürk – the father of Turks. I was curious as to what this image was doing here among frantic Christmas shoppers, so I went upstairs to check. Only then did I see that it was, in fact, a portrait of TS Eliot. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

The incident made me pause. I didn’t expect any other shopper in the same store, no matter how shortsighted, to experience the optical illusion that I had, unless they, too, happened to be Turkish. Having grown up with pictures of Atatürk on every possible wall, his image was so deeply ingrained in my subconscious that I saw him even where he wasn’t. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

I spent part of my childhood with my maternal grandparents. Grandpa, who was a retired army officer and a vet, kept a huge calendar with Atatürk photos on his bedroom wall. He went to sleep looking at the national leader and woke up knowing that he was being watched by him. Every December it was a major event to get the new Atatürk calendar and see what pictures of him had been printed for the forthcoming year. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

Once we got the calendar, I would sneak into Grandpa’s room and take it off the wall to check the pages. September’s Atatürk would wear modern European attire and a matching hat. January’s Atatürk would have a long military overcoat and binoculars through which he would observe the enemy from the trenches. My all-time favourite was April’s Atatürk because that was the only photo that had women in it. Here the founder of the nation would be seen ballroom dancing with a well-dressed Turkish lady while others watched admiringly from the sidelines. I would trace my finger over these idealised Turkish women, so familiar yet so unreal. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

My mother always told me to remember Atatürk with gratitude in my heart since he had saved not only the nation but us Turkish women. “If it weren’t for him, we would still be living like our sisters in some other parts of the Muslim world and men would still be marrying four women.” I would be very surprised when, in my first year at university, I started reading extensively about the late Ottoman era and came across a prolific feminist literature and movement in Turkey that dated back to the mid-19th century, if not before. I had always been told that gender consciousness, like all other fundamental and progressive things, was the creation of Atatürk himself. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

At school we would write poems and essays for the national leader, and swear allegiance to his legacy. We were told there would be enemies outside and inside, and we would have to defend him tooth and nail. For years all elementary schoolchildren repeated the national pledge: “I am a Turk. May my existence be a gift to the nation.” Recently, this long-lived oath has been abolished. It was long overdue.→ Photograph: Ersoy Emin

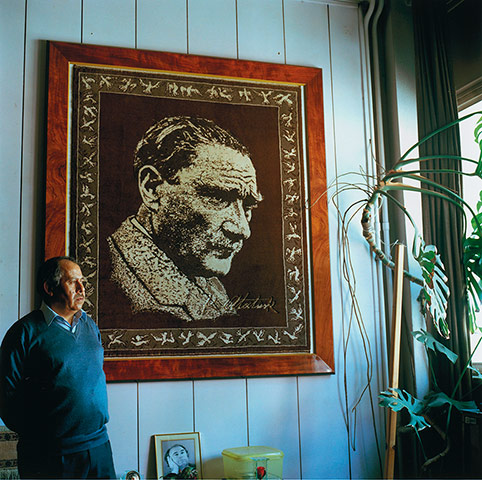

Yet today in Turkey, just like in the past, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s iconography bedecks every street and square. It is not only the state that constantly reproduces this imagery but also the citizens themselves. Pictures of the national leader adorn teahouses, groceries, liquor stores, lottery kiosks, hair salons, even the wooden boxes of the shoeshine boys or the trays of sesame bagel vendors. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

Atatürk’s image penetrates everyday life in Turkey like no other symbol or icon ever can. As you move around in Istanbul on an ordinary day, you will come across Atatürk’s pictures at least a dozen times in a couple of hours. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

This series of pictures, taken by the photographer Ersoy Emin, vividly portrays the cult of Atatürk today. In one of the images, a little girl is pictured with Atatürk in the background. She is crossing her arms and looking directly into the camera. She leans slightly back, as if deriving strength from the portrait of the leader. I see in this photograph reflections of many Turkish women. I see my own mother in that young girl. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

Pictures and statues of Atatürk in Turkey, despite being bountiful in number, are curiously limited in imagery. He is shown as either a military commander or a successful statesman. About to go to war or returning victorious. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

Yet as visible as Atatürk is, he remains equally invisible. We know so little about him. The photographs hide the man behind a thick curtain of repetitive poses. We are not used to seeing Atatürk in his daily life, relaxed and real. A few years ago, Besiktas municipality in Istanbul caused some controversy when it organised an open-air exhibition with previously unseen Atatürk photographs, which showed him swimming, eating, laughing… just like one of us. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

The cult of Atatürk was intensified by the military elite, especially after the coup d’etat of 1980. In 1981, the hundredth anniversary of Atatürk’s birthday, there was an extensive campaign across the country. It was a general rule that all government offices should have a portrait of Atatürk and a copy of his Address to the Turkish Youth. In schoolyards there had to be a bust of the national leader. Every ceremony would be organised around this bust. Atatürk was the centre of civic rituals, and anyone who damaged his busts would be punished by law. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

If you happen to be in Turkey tomorrow (10 November), early in the morning – at 9.05, a time every Turkish citizen knows by heart – you will hear the sirens blast. Drivers will get out of their cars. Pedestrians will stop walking. Vendors will stop hawking and everyone who observes this ritual marking the date and time of Atatürk’s death will stand up and freeze in respect. Time will stop. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

Atatürk’s iconography is as strong in Turkey today as it was in the past. Bumper stickers with his name have become quite popular. With the electoral victory of the conservative AKP, the secularist segments of the population have become more anxious and reactionary. This, in addition to several authoritarian steps by the government, have rekindled Atatürk fetishism. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

You might come across young people wearing Atatürk T-shirts. Some of them have Atatürk tattoos on their arms. Having a photograph of Atatürk in your house or workplace is a political statement. It is a symbol and a message. People see his picture as a sign of progress, westernisation, modernity; a bulwark against what they call the fundamentalisms of the east. → Photograph: Ersoy Emin

Whenever there is a cult of a leader, there are bound to be extreme feelings revolving around him: either mindless worship or outright rejection. There are those who put him on a pedestal, then there are those who think everything he did was wrong. At literary festivals I have met emotional Turkish readers who have told me it is the duty of every educated Turkish woman to represent Atatürk and his ideals. Others have accused him of cultural assimilation and suppression and totalitarianism, and said I should write a novel about all of this. It is almost impossible to speak about the positive things and the negative things in Atatürk’s legacy: you must either defend or attack him.→ Photograph: Ersoy Emin

As a novelist, I am interested in Atatürk as a human being. Not the Atatürk that would frown at us in our primary school classroom. Not the Atatürk whose eyes my class teacher had told us could watch us all the time and know when we did wrong. But an Atatürk with all his flaws, contradictions and merits, like all of us. Not a marble bust or a statue, but only a breathing, living story can help us to understand the reality behind the portrait • Photograph: Ersoy Emin