South Korean pop culture is so ubiquitous today, it’s fascinating to consider that back in the 1990s, local pop culture was not particularly well regarded at home, and no one outside the country knew much about it.

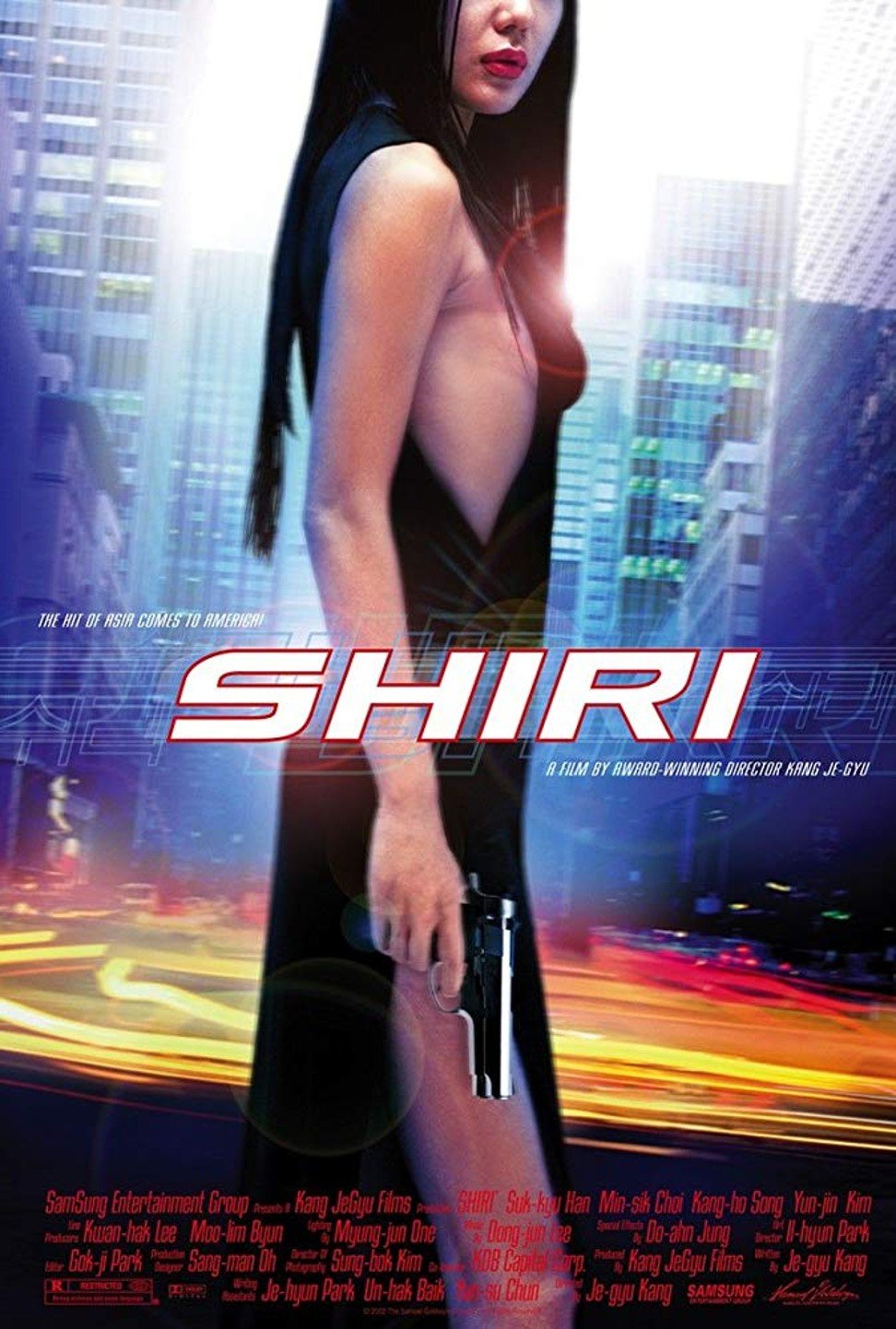

In terms of films, the big change came with the release of Jacky Kang Ge-yu’s melodramatic action romp Shiri in 1999. The film, which is known as the first Korean blockbuster, broke box-office records at home and piqued interest in the potential of commercial Korean films in Asia and the US. Although it did not start hallyu [Korean Wave] on its own, it was instrumental in its success.

Shiri’s phenomenal success gave Korean filmmakers a huge burst of confidence in their work, and this enabled them to successfully challenge the dominance of Hollywood films in Korea. It spurred investment in the film industry, and encouraged production companies, aided by the government-supported Korean Film Council (KOFIC), to market their films to foreign distributors.

Most important of all, it made Koreans excited about going to the cinema to see local films, and this paved the way for big hits like Joint Security Area, Friend, The Host, and the spectacular rise of Korean cinema at home and abroad.

Shiri is certainly not the best commercial film to come out of South Korea – even at the time it was praised more for its neat structure and clever audience pleasing characteristics than for its artistic qualities. But good planning meant that it achieved the holy grail of commercial filmmaking – it was a local film which dealt with Korean issues, but it could also be easily understood and digested by foreign viewers.

The plotting follows the careful structure of a Hollywood film in a textbook fashion, employs Hollywood storytelling devices, and leads viewers through the satisfying emotional ups and downs that characterise a good US blockbuster. But the content, which focused on espionage and counter-espionage activities between intelligence services in the North and the South, was uniquely Korean.

Shiri is a well-judged combination of an espionage thriller and a melodramatic romance. The story is hardly groundbreaking, but it is effective. Bang-hui (Kim Yun-jin) is a North Korean assassin who kills South Korean political leaders. After carrying out her murders, she becomes a sleeper agent in the South, undergoing plastic surgery to disguise herself, and posing as Myeong-hyeong, the owner of a fish shop.

Romance increases the stakes, as Myong-heong is having a relationship with Jong-won (Han Suk-kyu), the South Korean agent who is trying to track down her alter ego Bang-hui. Love and duty clash when North Korean agent Mu-yeong (veteran actor Choi Min-sik) slips into the South to steal a powerful bomb to blow up a North Korea/South Korea football match.

Shiri, which was produced on a budget of US$3 million to US$5 million, was a smash hit in South Korea, taking around US$26 million at the box office. Six million people in South Korea went to see it, with 2.4 million of those coming from Seoul alone, and it topped the year-end charts as Korea’s highest-ever grossing film at the time – it ended up taking even more money than Titanic in South Korean cinemas.

“The success of Shiri was a cultural, economic and industrial phenomenon and it paved the way for the emergence of subsequent blockbusters, creating the ‘Shiri syndrome’,” writes Jinhee Choi in her informative English-language book The South Korean Film Renaissance.

Koreans were thrilled by the way Shiri looked like an American film, and its accomplishments, both technical and in terms of box success, evoked a sense of national pride – even the military reportedly praised its depiction of espionage techniques. The film’s success reinforced the notion that made-in-Korea products were of good quality, an idea which was starting to take hold in the mass consciousness of the country.

Shiri was also released while the South was pursuing the Sunshine Policy, an initiative which was geared towards achieving more interaction between the South and the North. Consequently, the film was lauded for the way it humanised the North Korean spies, instead of portraying them as wholly evil in the usual stereotypical fashion.

The film may have been in the vanguard of the Korean Wave, but it didn’t appear out of nowhere. The post-war film industry had many ups and downs due to the changing political situation in the country, but it had produced a healthy number of classics, including The Daughters of Pharmacist Kim (1963) and the neo-realist influenced Aimless Bullet (1960).

The country had its own master filmmaker Im Kwon-taek, who’d already made around 80 films, and its own maverick director, Kim Ki-young, who directed the psychological classic The Housemaid in 1960. Im’s delicate and emotionally brutal Sopyonje, made in 1993, was the all-time highest grossing Korean film until Shiri.

The industry declined during the 1970s, but a new wave of talented art-house directors emerged in the early 1990s, a movement that was dubbed Korean New Cinema. This included filmmakers like Park Kwang-su, who made the historical To The Starry Island, one of the first films to address the personal impact of the Korean war, and novelist Lee Chang-dong, whose thoughtful, literate Peppermint Candy was released the same year as Shiri.

These art-house films and filmmakers were known to critics outside South Korea, something that paved the way for the international success of the commercial films that followed later. A programme of Korean New Cinema directors at the Hong Kong International Film Festival, curated by the late Wong Ain-ling, the HKIFF’s legendary film programmer and scholar, had stunned critics in the mid-1990s.

The new Busan International Film Festival had played its part by bringing international critics to the festival – it even provided them with personal guides and translators for the duration – to introduce them to Korean filmmakers and view their works.

Shiri director Kang, meanwhile, had made a blueprint for his big hit a few years earlier with the supernatural romance The Gingko Bed, which was a sizeable hit in South Korea in 1996. Kang, who was already adept at self-promotion, came to Hong Kong to promote the Gingko Bed in 1996, where it opened on 20 screens in Hong Kong – which was six more screens than Shiri would get.

Although it was a time-travelling romance, based on a supposed Korean myth that Kang had invented, it was similar to Shiri in the way that it combined action with romance and a very modern sheen. (Although Kang has always vehemently disagreed, many felt he used Hong Kong action films as a model for The Gingko Bed.)

“I used my imagination to make something new,” Kang told me in an interview in 1996. “I decided that what I wanted most was for the audience to enjoy the movie, so I tried hard to make it accessible. I wanted people to find it easy to follow.”

During that interview in 1996, Kang and his producer T.J. Chung lamented the difficulties of raising money for Kang’s next film, noting that it was about the controversial subject of North/South espionage. “A lot of people want to invest Jacky Kang’s films,” Chung said, “but of course, nobody wants to put their money into this one.”

That difficult-to-fund project turned out to be Shiri, the film that would change South Korean movies forever.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook