A lot of older people think, ‘Oh, everyone knows The Beatles; everyone knows John Lennon.’ And that’s simply not the case,” says Sean Ono Lennon. “I meet my niece and nephew’s friends, I talk to Gen Z kids, and some of them don’t know the difference between The Beatles and The Monkees, I swear.” The son of the late Beatles star and artist Yoko Ono might have a point. For anyone over a certain age, the Fab Four are an immutable part of the culture, as constant and familiar as the air we breathe. But who says it’s going to stay that way?

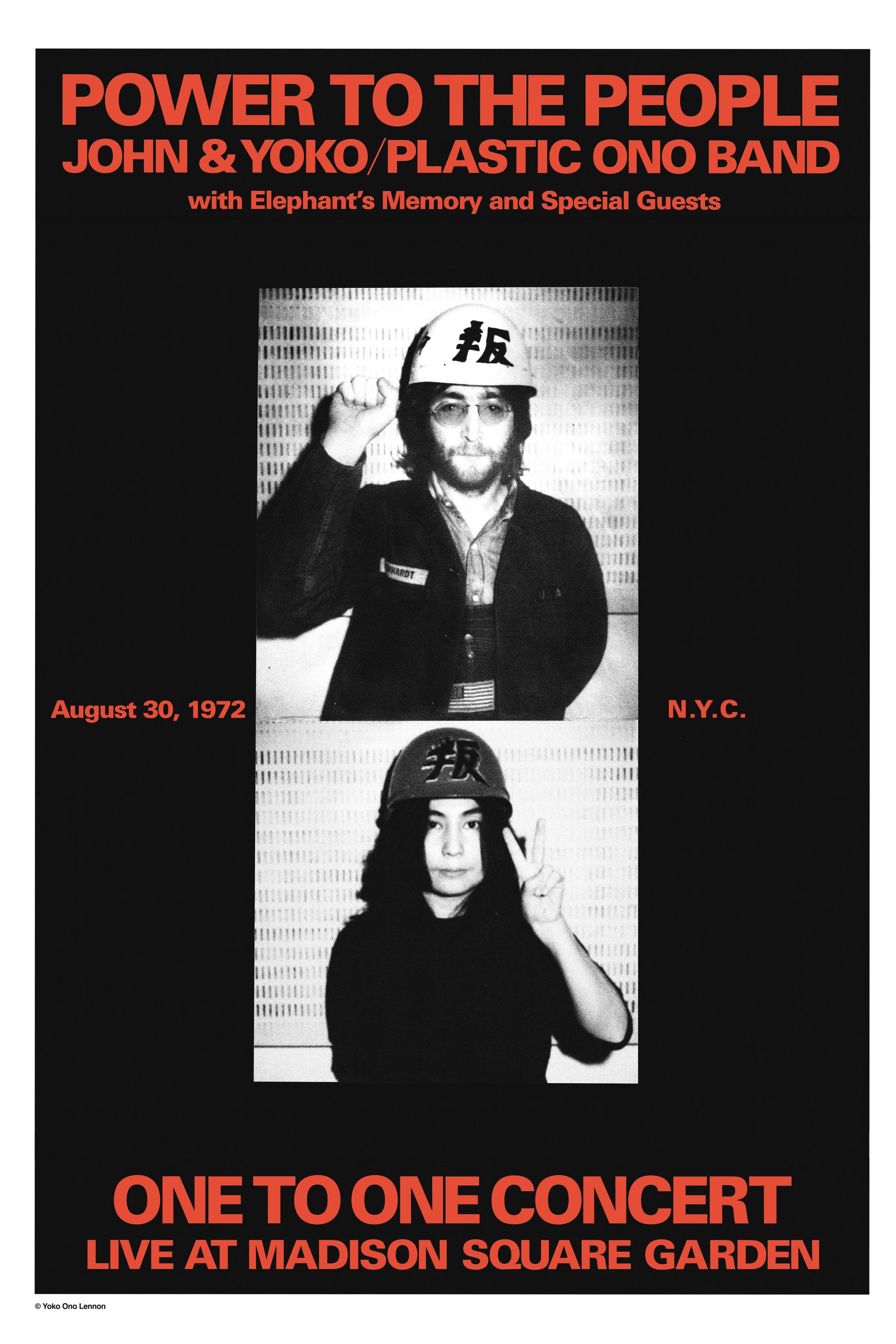

This was, in short, the core motivation behind Lennon’s new project, a lush new boxset of 123 remastered recordings by John and Yoko, during the period when their political activism was at its most daring. The release follows on from this year’s documentary film One to One: John & Yoko, which focused on the couple’s 1972 benefit concert for the children at New York’s Willowbrook school (who were victims of a massive abuse scandal) and their politically radical life in Greenwich Village in the early 1970s. The boxset contains extensive, cleaned-up recordings from the performance and others around that time, with George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Frank Zappa, Stevie Wonder and Keith Moon among the collaborators.

“If people think we need to stop putting out new versions of this music, I think they’re very wrong,” says Lennon. “Because I don’t want to live in a world where people don’t know that music. So I have a duty to keep putting it out and making it sound as good as possible, and finding ways to get young people interested. And it’s not just for me and my parents. It’s for the world – I don’t think the world can afford to forget The Beatles or John Lennon.”

There is something faintly surreal about speaking to Lennon, who resembles his late father so very much, facially. He has the same long, ovular face. The same shrewd eyes. (His styling doesn’t exactly discourage comparisons either: on our call today he has long, straight hair, a beard, and tinted glasses rest on the bridge of his nose.) At 50, he is now a decade older than John was when he was murdered, 45 years ago.

Often, the children of celebrities take pains to obscure their background, lest they be hit with accusations of nepotism, or professional privilege. Lennon, though, wears his lineage with pride. Like his half-brother Julian, Lennon is also a musician, having been a member of the bands Cibo Matto, The Ghost of a Saber Tooth Tiger (formed with his longterm partner, Charlotte Kemp Muhl), and the Claypool Lennon Delirium, as well as the revival of the Plastic Ono Project, his parents’ former musical group, which Ono revived in 2009. “Until the 20th century, most people did what their parents did,” he says. “It’s quite natural. But I do think in the modern world it seems weird, because most people expect you to reject your parents in a way, especially if they were famous. But there are only really two options – go out of your way to avoid what your parents did, or embrace it.”

While he was just five years old when John was shot dead in New York, performing has been a way of connecting with his late father. “I first was interested in music because of my dad,” he says. “I always felt like music was a way of getting closer to him.” He smiles, ever so slightly.

Lennon gives long, considered answers to the questions I pose, tightening up only slightly when I ask about Ono’s current life, as a 92-year-old retiree. “I live with her mostly, actually,” says Lennon. “I try to give her privacy now – she doesn't want to do press and she’s not interested in being a public figure any more.”

“It’s funny,” he says. “People always talk about how I have grown up in the shadow of my dad – which is true, but my mum really did. She had a thriving art career, and then as soon as she got together with my dad, that sort of went out the window for a while. People think about how Beatles fans didn’t accept Yoko, but the avant garde fans didn’t accept The Beatles! The modern art community was very snobby about rock and roll.”

It’s such a cliché to say ‘The world wasn’t ready,’ but I think in the case of Yoko Ono, it’s really applicable

Listening to and reading the material in the new boxset (titled Power to the People), one thing that’s striking is just how significant Ono was, as an artist and activist. Over the past few years, there has actually been a notable shift in the public’s perception of Ono – from the longstanding smear as the “woman who broke up The Beatles”, towards a more appreciative recognition of her work and life.

“At that time in England, when my dad and mum got together, it was really shocking to see a British guy with a Japanese woman,” says Lennon. “Then you add to that the fact that she wasn’t just arm candy, she was a really radically weird and interesting artist – incredibly unconventional and wild, in terms of the way she viewed the world.”

Even before getting together with Lennon, Yoko had been disowned by her parents for a previous relationship (her second marriage, to artist-producer Tony Cox) that flouted cultural norms. “She came from this conservative world, and she was too radical for Japan,” says Lennon. “She was too radical for swinging London, too. It’s such a cliche to say ‘The world wasn’t ready,’ but I think in the case of Yoko Ono, it’s really applicable.”

There was also, as Lennon points out, a lot of “unnecessary animosity” directed at his mother. “There was a small degree to which she didn’t make it easier for some people either,” he says, tilting his head pragmatically. “It’s a complicated story. But the bottom line is she was misunderstood, and she was misunderstood for over 50 years. And I think she is finally being considered for who she is as an individual.”

Another factor in this re-framing of Ono’s image has been Get Back, the 2023 Disney+ series composed of vivid, illuminating behind-the-scenes footage from the recording of Let It Be. Ono features intermittently in the series, and the band’s acceptance of her presence completely undermines the longstanding notion of her as a destabilising interloper.

That spellbinding series was notable for its use of AI technology in restoring the archival footage. AI – a rightly touchy issue for many artists – was also used to help isolate John’s vocals in the assembly of the “final” Beatles song, “Now and Then”, released two years ago. “I think people really misunderstood what we were doing when we said ‘AI’,” insists Lennon. “Because really, what it was, was a better way of filtering noise out of a track. It wasn’t about creating anything – it was sophisticated noise filtering.”

Get Back was most illuminating on two fronts: firstly, as a glimpse into the band’s immediate creative process; and secondly, as a look at the unguarded human personalities within the group. Power to the People, though, brings to the fore a different side of Lennon’s life, his politics. The 1970s saw John and Yoko organise on many fronts at once; one minute he’s campaigning against the US war in Vietnam, the next against the imprisonment of poet-musician John Sinclair. “To me, it feels like his activism came from his first principles – peace and love and humour – that core belief system that he had,” says Lennon.

Lennon’s own politics are perhaps a little harder to pin down than his father’s, though he has advocated for progressive causes in the past, and continues to proselytise John and Yoko’s message of peace above all. “In terms of where the progressive movement has gone, I do think John and Yoko’s philosophy has been too much forgotten,” he muses. “My dad always said that what [the establishment] can’t deal with is love and humour. And I think that the young activists trying to change the world would achieve more if they were loving and humorous, not violent.”

He does, however, voice doubts about the efficacy of protest in the modern age – and of modern-day songwriters engaging in it. “I always remember after 9/11, there was the biggest peace march in history, against the potential invasion in Iraq. And about a week later, they invaded Iraq. It didn’t move the needle at all. Whereas during the civil rights movement, those protests really had an impact on the culture, on the government. People listened.”

He continues: “If Taylor Swift wrote a song about Gaza, I don’t know that it would have the same impact as when, say, my dad wrote ‘Revolution’. I think people are more cynical than they used to be. Part of it is good, because we’re less enamoured with celebrity – we don’t worship in the same way. We’re more aware that these are human beings, because we see them, you know, going to the dentist on Instagram. It’s easy to be cynical about it… and I don’t know what the answer is.”

I don’t know what the answer is either. But if there’s one to be found, then Power to the People – a fascinating time capsule of energised political protest and liberating ideas – is a good place to start looking. Despite Lennon’s fears, The Beatles are not on the verge of being forgotten. Their music endures, and will continue to for decades to come. But what John and Yoko stood for might be just as important to remember.

‘Power to the People’ is released on 10 October via Universal Music Group