Drought is forcing Namibian desert elephants to seek water near human settlements. But human encounters with the giant mammals frequently end in tragedies. Elephants are being shot, and their population is shrinking. A conservation project using a combination of GPS data and high-resolution satellite images is trying to help the two species coexist in peace. Without it, the rare desert population might soon go extinct.

About 24,000 elephants live in Namibia, a southwest African country known for its desert landscapes and wildlife parks. Most of them dwell in the lush greenery of Etosha National Park in the north of the country and near the border with Botswana in the northeast.

But over the centuries, smaller groups of elephants have ventured into and learned to survive in the more arid plains in the western Kunene region. These elephants fascinate zoologists for their ability to handle the harsh weather conditions in the area, including strong, ice-cold winds and alternating droughts and heavy rains.

"Somehow, these elephants know when the winds are coming before they come," Christin Winter, Conservation Program Manager at Namibia's Elephant-Human Relations Aid (EHRA) charity, told Space.com. "They know where to hide from it; they know where water will pool when it rains because they remember it from previous seasons."

But the extreme conditions are also forcing these elephants to approach human settlements. When droughts hit, elephants have no choice but to share water resources with humans, despite knowing all too well that people equal mortal danger.

Before the Namibian war of independence, which raged from the mid-1960s until the end of the 1980s, locals in the deserts of western Namibia knew how to live with elephants. But poaching for meat and ivory decimated the population so much that the elephants disappeared during the war. They began returning in the 1990s, but by then, social change erased the traditional knowledge. New settlers came into the region and brought with them many misconceptions about the giant mammals.

"There is a lot of fear and folklore around elephants — for example, that they eat people," Winter said. "But there have been other problems. Elephants could break infrastructure, even damage houses. If you bump into them at night and you don't know what to do, it can get dangerous."

Local farmers frequently resort to defending their property with brute force. Elephants get shot at, wandering off wounded and dying in the fields. From a population that once counted around 3,000, only 150 animals remain in the region today.

"Over half of the local population of desert elephants was lost within a few years," Winter said. "It has stabilized a bit, but there are also other environmental pressures that prevent calves from surviving. We have a very low number of adult elephants and very few teenagers, which is obviously not great."

In a bid to help locals coexist with the magnificent species without either side suffering harm, the researchers fitted three elephants in the most affected group with GPS collars in 2021 to track their movements. Whenever an elephant approaches a village or farm, the "Earth Ranger" system generates an alert that gets shared with the community in real time.

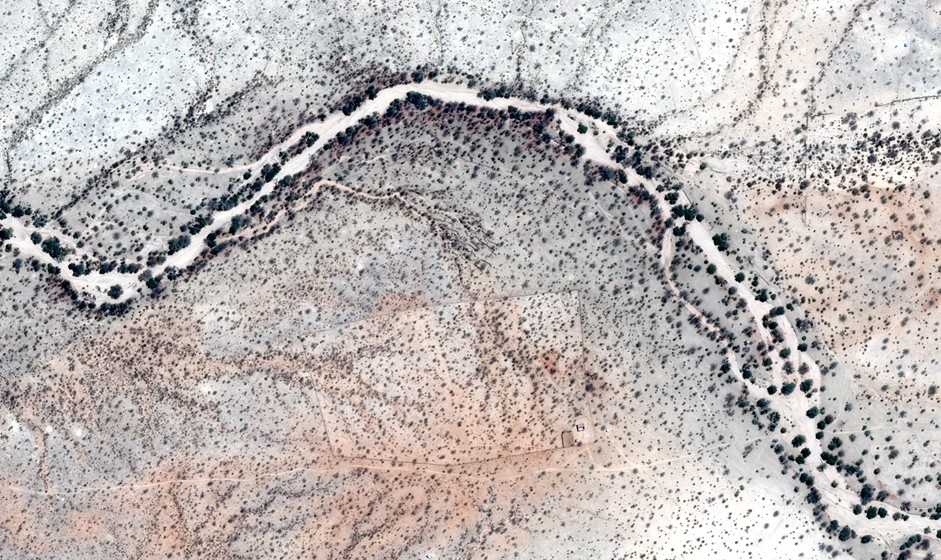

Since the roll-out of the geofencing system, the number of incidents involving humans decreased, Winter said. To make things even better, the researchers are trying to combine the GPS tracking data with high-resolution images from Airbus' Pleiades Neo satellites to understand why and when the elephants visit villages and farms. They collected data during the droughts and the subsequent rainy season to understand how the elephants' movement patterns change throughout the year.

"The elephants will choose a place even within a risky environment where they feel the safest and where there is vegetation and water," Winter said. "When there is enough water and food, that for them outmatches the risk of dying from shooting, which surprised us. They are willing to risk the consequences."

Known for their impeccable memory, the elephants remember the tragedies that people inflicted on their families, Winter said. They only approach villages at night and move almost "like ghosts," running away at the first hint of human presence.

The researchers hope the satellite data may help design new strategies to make human-elephant coexistence easier.

"We are trying to protect the natural water points and place troughs and dams strategically so that the elephants don't need to go through the villages at night," Winter said.

The satellite images help identify elephant hotspots, which then enables the researchers to negotiate with farmers.

"The big aim is to identify corridors and find ways to protect that habitat for the elephants," Winter said. "We had one farmer who saw the data and realized that one corner of his farm was almost owned by the elephants, and he allowed us to have that corner in exchange for protecting the rest of his farm. With compromises like that, we can reduce the conflict and give the elephants a safe spot to be."

.jpg?w=600)