Our cultural touchstones series examines works that have had a lasting influence

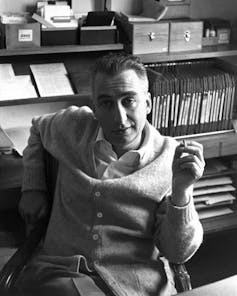

In 1967, French literary and cultural critic Roland Barthes published a short essay that would have far-reaching influence. Titled The Death of the Author, the essay argued that, for the purposes of interpretation, the intention of the author is irrelevant, even stifling.

In asserting that the author is irrelevant to the act of interpretation, Barthes put in play a wealth of interpretive possibilities. As he put it in the essay’s closing line, “to give writing its future, it is necessary to overthrow the myth: the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author”.

To write, according to Barthes, is to enter into language, inscribe oneself in its symbolic space and, in doing so, efface oneself. He initially presents the resulting disconnection between author, text and reader as universal:

No doubt it has always been that way. As soon as a fact is narrated no longer with a view to acting directly on reality but intransitively, that is to say, finally outside of any function other than that of the very practice of the symbol itself, this disconnection occurs, the voice loses its origin, the author enters into his own death, writing begins.

The idea that authors do not lend texts their exclusive meaning derives from this universal principle that to write is, in a sense, to die. What Barthes largely means by the playful metaphor of “death” is that the author’s intentions and consciousness are withdrawn. Readers cannot access either, but have only the text before them.

Though Barthes wonders about this universal principle, he suggests the concept of an “author” is a product of relatively recent times. The author, he argues, is a “modern figure”. It is “a product of our society insofar as, emerging from the Middle Ages […] it discovered the prestige of the individual, of, as it is more nobly put, the ‘human person’.”

So while Barthes suggests that the author’s “death” in the act of writing has “always” happened, he also historicises the figure of the author. He differentiates the creative practice of writing from the “person” of the author.

He also implicates the concept of authorship in “capitalist ideology”. An author’s name on a book cover is associated with a form of property: intellectual property, copyright. Writing is solidified under one proprietary name, even though it is, at least in part, a collective endeavour that also involves editors and readers.

Intentional fallacies

There were precedents for Barthes’ criticism of our attachment to the “person” of the author". British writer Zadie Smith pointed out that “it’s easy to read The Death of the Author as a series of revolutionary demands, but it’s worth remembering that it was also simply a licked forefinger held up to test a wind already blowing.”

In the early 20th century, T.S. Eliot’s notion of poetic “impersonality” established a precedent for Barthes’s concept, expressing an ambition on the part of the writer to erase themselves from the work, so that it might stand alone.

US based literary critics William Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley offered a drier elaboration of similar ideas in 1946 under the name of the “intentional fallacy”. For Wimsatt and Beardsley, placing excessive emphasis on authorial intention led to fallacies of interpretation. We may imagine we know what the author means to say, but we only have the text present before us, not the author, so we are mistaken if we think we can know their intentions.

Wimsatt and Beardsley’s argument has much in common with Barthes’, though it lacks the latter’s panache. Where the Americans spoke of a “fallacy”, the Frenchman declares the author’s irrelevance to be fatal.

In declaring the death of the author and the birth of the reader, Barthes precipitated a revolution. His essay is a product of the unrest in France that would culminate in the student riots of May 1968. Barthes’ anti-capitalism precipitated ideas that led to the uprising.

Barthes’ work of this period also exemplified the transition in French thought from structuralism to poststructuralism. Structuralist critics had sought to reveal underlying patterns through rigorous analysis of cultural signs. Poststructuralists called into question the distinction between surface details and underlying structures that was the foundation of structuralism.

Barthes early work had taken a structuralist approach. In many ways, his attack on the notion of authorship manifests the provocative logic of poststructuralism.

For teachers of literature, the notion of the death of the author has been preeminent for some time. These days, many literary scholars and even some writers accept Barthes’ premises. From literature departments to creative writing programs, the idea of the death of the author has become something of an orthodoxy.

Manifested experiences

Barthes’ ideas about authorship had their detractors. Critics came forward almost immediately. Many of the defenders of authorial intention came from the ranks of colonised people and postcolonial writers. For many of these critics, the author’s presence and humanity in the text are complementary to anti-colonial politics.

The death of the author and the play of signification might have served to liberate readers. But such liberation seemed to many anti-colonial writers not to be located in the sphere of emancipatory anti-capitalism, but in the zone of regressive forms of anti-humanism. To turn to the typewriter or the pen was meant to be a means of liberation, not death.

Poet Édouard Glissant, from the Carribean island of Martinique, is one example of an intellectual from a colonial society who questioned Barthes’ premises. Within two years of Barthes’s essay, Glissant had compiled some of his existing writings with new essays to offer a powerful rejoinder. His book Poetic Intention (1969) develops a theory of difference in relation to artistic and literary intentions. He would elaborate this theory until his death in 2011.

Glissant seeks a literary criticism that will pursue more than the “hidden purpose of the author”. He wants writers to consider “the manifested experience of a people”.

Like Barthes, Glissant is aware of the limitations of fetishising authorship. But he goes further. He enters into a tradition of black intellectuals, such as Frantz Fanon, who see the meanings of literary works as manifestations not of hidden psychic structures, but collective social endeavours.

Like Glissant and Fanon, Edward Said saw writers as representatives of their people. “Intention,” he argued, “is the link between idiosyncratic view and the communal concern.”

Said was a student of French structuralism and poststructuralism. He was both knowledgeable about and critical of figures such as Barthes and Michel Foucault. In his book Beginnings (1975), Said politely took issue with the idea of the death of the author:

despite recent genuinely investigative tendencies in criticism (in, for example, the work of Roland Barthes), certain conventions, persisting as unexamined vestiges of the whole history of ideas, have a strong hold […] But certain questions – such as the nature of the author’s (beginning and continued) authority over his text […] remain relevant.

His reasons for insisting on the author’s relevance were complex and abstract. Said was a Palestinian intellectual and unwavering critic of the forces of empire and colonialism in the US, Israel and elsewhere. In his later work, he would increasingly come to link intention to colonialism, and to its critique.

By the time of 1994’s Culture and Imperialism, Said had broken with key French intellectuals – notably Foucault. On one page of that book, he names a series of liberation struggles (“Algeria, Cuba, Vietnam, Palestine, Iran”), asserting that these struggles were not only against the structures of empire (though they were), but also against the use of imperial force.

Recognising intention’s role in texts and social relations means recognising agency. With this recognition comes an awareness of the operations of power and the capacity to resist. For Said, acknowledging intention meant acknowledging the agency of those participating in varying forms of resistance.

As time has worn on, criticism of the death of the author along these lines has intensified. In a 2017 essay, First Nations (Goorie) novelist Melissa Lucashenko asserted: “The author is not dead. More specifically, the Aboriginal author is certainly not dead, a double happiness!”

Similarly, Wiradyuri author Jeanine Leane has taken aim at two aspects of Barthes’s essay: its whiteness and the way its openness to the reader can serve to justify appropriation. The birth of the reader, she suggests, always carries with it the potential for such appropriation. For Barthes, Leane writes,

a text’s unity lies not in its origins, or its creator, but in its destination, or its audience. This view aptly sums the long trajectory of European appropriation, blindness to its own cultural standpoint, western literary colonialism, and the consumption of minority cultures by invading, colonising powers.

In the more than half a century since its birth, Barthes’ notion that the author is dead has been incredibly influential. Yet his approach has arguably encouraged the unitary model of authorship that it sought to avoid, his decoupling of authorship and humanism giving rise to ongoing postcolonial critiques. Especially in relation to anti-colonial thought, rumours of the author’s death are greatly exaggerated.

Michael R. Griffiths does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.