I lived in a violent relationship with my second husband from 2001. I was estranged from my family as he destroyed my mother's property while I was in hospital following the birth of our first baby. It was on our way home from the hospital, he screamed at me while driving, [he said] if I ever left him he would kill me. Then we moved to Wagga.

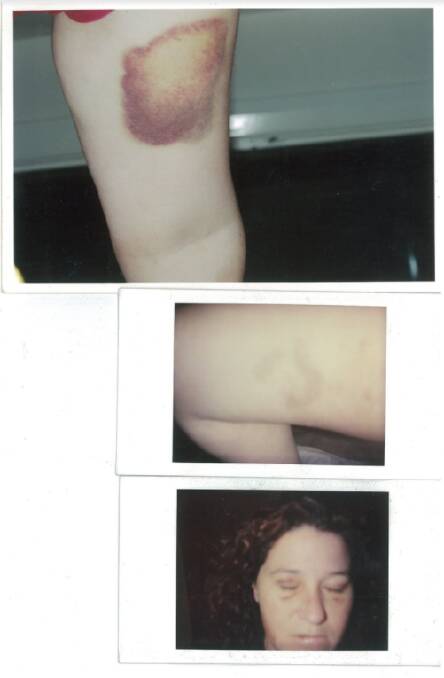

Meet Rach. By the time she knew she had to leave her abusive husband to protect her three children and herself, she'd been threatened multiple times. When she mentioned separation, the attacks became more frequent and even more terrifying. Now she and her children live in peace and safety in Wagga. Yet even that peace and safety comes at a price. Rach has built a panic room, with steel bars and doors, in case she ever needs to lock herself and her kids in.

This is what peace looks like to survivors of family violence.

New research this week showed clearly that women are at the greatest threat of fatal violence during the process of separation. As separation draws closer, men proceed to escalate abusive behaviours: controlling, stalking, monitoring.

But when the victim and offender have finally separated or are negotiating reconciliation, the period of escalation which precedes the lethal violence is often very short, on average about three months. Just three months.

Hayley Boxall, lead author of this report from Australia's National Research Organisation on Women's Safety, shows killers fit into three categories. First, there are the fixated threat offenders, who account for one in three of these murders. They're the ones who look normal from the outside - the "good guys". It's in this category where separation as a trigger for murder is most common.

Boxall's team describes the second category as "persistent and disorderly", accounting for 40 per cent of murders - killers with significant histories of violence towards their partners and others, and mental, emotional and physical health problems. They are more likely to be Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, with complex histories of trauma and abuse.

The third pathway, accounting for one in 10 deaths, is described as deterioration/acute stressor - non-Indigenous, older and also with significant emotional, mental and physical health problems.

Jane Monckton Smith, a British criminology professor from the University of Gloucestershire, also researched patterns of fatal violence by men against women. She analysed 370 murders by men of women in Britain to find eight common steps which lead to the murder of women by men. Monckton Smith, the author of In Control: Dangerous Relationships and How They End in Murder, describes the Australian research as an important addition to our knowledge.

"It will have the potential to change policy and potentially save lives," she says. "The idea of journeys and perpetrator psychology is an area that is relatively under-researched, so this will be an important addition to knowledge."

And Boxall says this research will put the emphasis on the community, not on individual women. More often than not, these women have contact with different types of services at different stages of their relationship, and have talked about what is going on in their lives. But no one picks up the signs - or if they do, it is too late.

"We're too reliant on women to identify when they're at risk of homicide, and to be able to articulate that. It moves the responsibility to family members, to friends, to statutory systems and services that are engaging with these women," she says.

Intimate partner homicide is decreasing in Australia, consistent with homicide trends in general. That, says Boxall, is likely to be because of improved hospital responses and the lack of availability of guns.

"But the reality is that one homicide every 11 days is too many. These homicides are preventable and we should still be working towards zero," she says.

We would all imagine that our police officers would be part of that work - the ultimate good guys.

But two women, whose pseudonyms are Michelle and Gina, are part of a support group for those who are survivors of their violent police officer partners. Michelle lived in country Victoria at the time of the incidents, Gina in Goulburn.

Michelle, whose case attracted national attention, says that when your partner is a police officer who is violent, you are assumed to be a liar. She experienced physical and emotional abuse from her partner, and details of her escape plan were leaked to her partner, who then assaulted her. Eventually she received an apology from the Victorian police.

In Gina's case, her former partner's knowledge of systems were used to get the young woman charged with assault occasioning actual bodily harm. Her conviction resulted in an AVO being placed against her. She was finally cleared in the district court, and the AVO quashed. The entire nightmare took over 18 months.

Michelle says: "The biggest thing is understanding the system you are dealing with. Police perpetrators have priviliged access to systems and access to firearms, and they understand how to use systems to abuse you."

She now has a very calm and settled life with her children, and says that living openly has given her strength.

"Why be on the run? We've moved back to the family home and have a well-worn safety plan. We are taking it back," she says.

That's been Rach's approach too.

She and her friends have started working for the future, with Taster, a social enterprise using early intervention models. It's in the early stages, but it's where young people can come, meet each other, learn new skills.

And she feels lucky.

"I attribute the installation of the panic room to be the reason I am still alive today," she says.

Boxall says there is more we can do: integrated systems and information sharing across services and authorities; better bystander training (she says everyone is a potential reporter); integrated alcohol and drug services with behaviour change programs; and ensuring that victims' voices are out there, telling their stories.