It’s the 1986 World Series, Game 6, at Shea Stadium in New York, bottom of the tenth inning. The Boston Red Sox, who haven’t won the championship since 1918, establishing a reputation for dramatic unsuccess, have just taken a 5–3 lead over the New York Mets. Three more Mets outs and the elusive Series at last will be Boston’s. In the press box, high above the field, I’m a rookie magazine reporter, not long out of college, seated alongside Roger Angell of The New Yorker. As a boy, I reread The Summer Game, a collection of Angell’s early baseball essays, so many times, and stuffed so many escaped pages back into the paperback binding, that it resembled a bundle of careworn love letters.

Angell, who died this year at 101, was the finest writer ever to turn his consistent attention to baseball. He started writing about the game for Holiday magazine and became a regular baseball correspondent for The New Yorker in 1962, where he was a mid-career fiction editor. Inspired by John Updike’s elegiac meditation on Ted Williams’s last game, in 1960, Angell found that the sport allowed him to access a startling depth of talent for prose. His baseball billets-doux were extended performances of admiration and seduction set forth in Macoun-crisp sentences. Right away, in 1962, here he is describing Willie Mays on the basepaths: “He runs low to the ground, his shoulders swinging to his huge strides, his spikes digging up great chunks of infield dirt; the cap flies off at second, he cuts the base like a racing car, looking back over his shoulder at the ball, and lopes grandly into third, and everyone who has watched him finds himself laughing with excitement and shared delight.” Even as a boy, I could tell that caring was the subject within the subject—how wonderful in life it is to be astonished by others, and to tell why you love what you love.

Among Angell’s most celebrated articles were his annual November reflections on the season past. The more compelling the victorious team, the springier Angell’s sentences. He was an inveterate front-runner—and a demanding viewer. During routine ballpark visits, subpar play by his team might find him abruptly departing the premises. Yet which team truly was his became a matter of complexity. As a boy, he’d supported the Giants. But The Summer Game suggests that during the libidinous 1960s, his ardor strayed, and he set his ballcap first for the fragile Red Sox and then the boisterous Mets. He also tended to fall, in passing, for every team he covered.

And so now here in 1986 we were, and he would have to choose. Angell always kept his scorecard in pencil, and supplemented this factual accounting of the game’s events with exultant red-ink marginal commentary. His Game 6 scorecard, he later wrote, resembled “a third grader’s valentine, with scarlet exclamation points, arrows, stars, question marks, and ‘Wow!’s scrawled thickly across the double page.” As the bottom of the tenth inning began at Shea Stadium, all around us the press box emptied. With the Red Sox ahead by two runs and poised to win, the other reporters were preemptively boarding the creaky press-box elevator down to the basement level, so as not to miss the Red Sox players bursting into the clubhouse, rejoicing in their long-awaited triumph.

In person, I found Angell to run cooler than his written persona; he was more than a little intimidating. When he held up a stern hand and insisted that we weren’t leaving, mine was not to question. So it was that we two and the man at Angell’s other elbow were the only three members of the press who remained there to witness a seminal baseball unraveling, as the Mets seized the victory by scoring three times, the decider after a modest ground ball trickled between the sore ankles of the Boston first baseman, Bill Buckner. When the Red Sox completed this debacle by also losing Game 7, team members wept. “It is not such a bad thing to see that men can cry,” Angell wrote. Then he flung aside sentiment, decided that the Red Sox and their fans whined too much, and embraced perfidy and New York, declaring, “I am a Mets fan.”

Many people who feel a deficit of closeness in their lives are drawn to supporting teams. The defining moment of Angell’s New York childhood came when his New Yorker editor mother, Katharine, left her family to take up house with her colleague, the writer E. B. White. Angell grew close to White, the stepfather he and others called Andy, even as winning his mother back became a lifelong preoccupation: “Again and again, my mother,” he wrote, long after she’d died. (Of Katharine, the writer Nancy Franklin explained, “As an editor she was maternal, and as a mother she was editorial.”)

Angell’s third-grade report card read: “Roger has begun to make an effort to conform to our standards of behavior, but this is such a recent change that it requires continual checking.” During boyhood, he emulated the eccentricities of ballplayers, including his favorite, the Giants’ left-handed screwball pitcher Carl Hubbell. Snapping off screwballs so strained Hubbell’s arm, Angell learned, that over time the pitcher’s left palm had permanently inverted to face outward. So Angell took to walking with his own left arm similarly contorted, hoping his mother would notice. When she did, she emended him: “Don’t do that, Rog!”

Years later, Angell happened to tell George Plimpton about this. Plimpton’s literary signature was a form of participatory reporting in which he, as an athletic mediocrity, played with professionals and then described the experience. As Plimpton listened to Angell describe his Hubbell twist, his eyes narrowed. Soon word drifted back to Angell from others that Plimpton had just confided something remarkable about his childhood. Plimpton said his enthusiasm for Carl Hubbell had run so deep, he used to—can you believe it!—walk around New York with his arm hideously twisted in homage. Angell said he didn’t mind the bio-pilfering. Inhabiting other people’s lives came naturally to Plimpton, and here he’d been presented with something irresistible, the chance of playing two other people at one time.

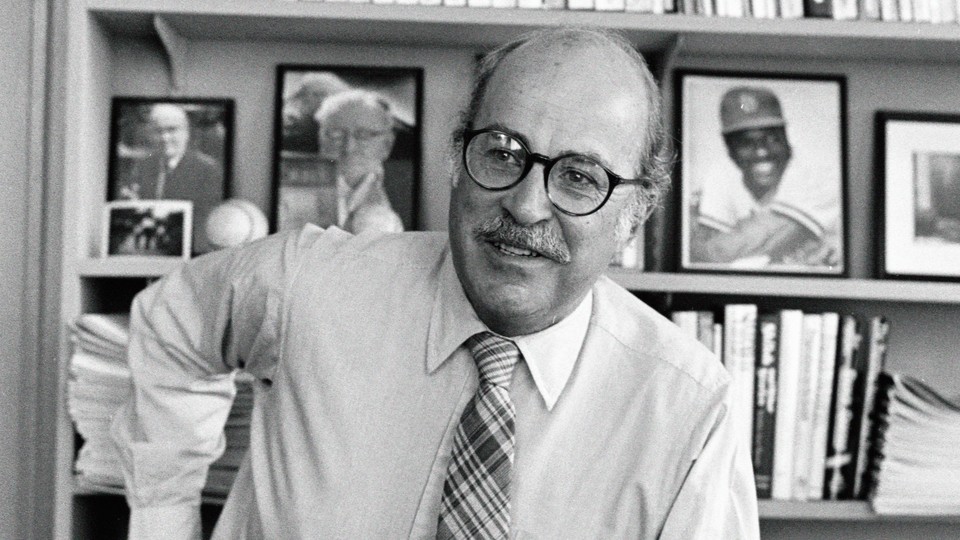

Angell lived his adult life three blocks from where he was born. After his World War II military service, and about a decade at Holiday, he joined his mother’s and stepfather’s side, taking a job at The New Yorker. Tall and lanky, Angell came to the office emanating fresh-laundering in shirt and tie (he looked especially well in lavender), penny loafers, and trousers he ordered cut to sufficient length that the tops of his socks would never, ever show. The magazine “surrounded” him, he said, and a granddaughter recalled, “I thought The New Yorker was how he referred to himself.” As an editor, he counseled compression—that the most difficult task was to “write short.” He liked telling the story of E. B. White trying out nine different beginnings for Charlotte’s Web, the lesson there that you should always seek to do better. In that spirit, Angell sometimes sent younger writers edits on their already-published pieces. His own editors, however, could find him combative, resistant to their counsel. Angell’s colleague of more than 50 years, Calvin Tomkins, considered him to be the most complicated man he ever knew.

Angell liked to be surprised by fiction, by ballplayers—was open to novelty in the exterior world. His best friend for many years was the writer of surreal short stories Donald Barthelme. But Angell’s own perimeters were fixed in routine. Anybody who stepped over the gunwales of his sailboat learned that there was one proper way of knotting half hitches and bowlines. To tie one otherwise was to be upbraided by “Captain Whitelips,” as one victim groused.

Angell was a writer who suffered deadlines. When one darkened his horizon, a Latin sign went up on his office door: Timor scribendis conturbat me—“Fear of writing terrifies me,” adapted from the Catholic Office for the Dead. Telephone callers instantly understood Angell’s looming obligation by the frenzied tone with which he answered. He would become unable to sleep, which made him even more cranky and fretful. From 1976 to 1998, he wrote Greetings, Friends!, the annual New Yorker Christmas poem, sophisticated doggerel that name-checked people whose doings had had resonance over the past year. Angell’s private title for these tidings was “My Christmas verse boulder.” How beside himself he got over his writing was the coefficient of how much he cared about it. When the 1989 World Series between the Oakland Athletics and the San Francisco Giants was interrupted by an earthquake that took down bridges and killed 63 people, Angell flipped out. Amid the temblor, he’d lost his notebook.

Still, he was good at fun. Angell and his second wife, Carol, created elaborate guessing games for visiting children. With New Yorker cartoonist pals, he dreamed up ideas for drawings and captions. One that Ed Koren especially admired read: “Camp Winooskie: A camp for somewhat gifted boys.” At his vacation home in Maine, Angell led friends into his bedroom to see the homemade “Decision-Maker” he’d posted on the wall, a metal arrow that, when spun, circled past Why Not? and Sure Thing! and Yes! as gravity guided it inevitably down, every time, to No! That comic flair lifted his baseball writing, too. Codifying the windup variations of the Red Sox pitcher Luis Tiant, he named one “Call the Osteopath”: “In midpitch, the man suffers an agonizing seizure in the central cervical region, which he attempts to fight off with a sharp backward twist of the head.” He resisted the efforts of baseball sentimentalists. “Baseball is not a metaphor for life,” Angell once said. “It’s just a bunch of big kids playing a game.”

For those who knew him, it could be difficult to reconcile the warm, sparkling companion in the articles and poems with the less easeful man at sea. Angell was so engaged in the world, knew so many things—could readily reference recondite scientific theory, old Polish dances, and obscure novels for boys—that even close friends found the prospect of his judgment a little scary. As he aged into granddadly geezerdom (his way of putting things), he mellowed, even while retaining his youthful enthusiasm. He made new friends and celebrated new films, new writers, new politicians (Barack Obama, especially), and a belated new favorite ball club, the Yankees. His 80s and 90s also featured a pair of stunning memoirs—Let Me Finish and This Old Man—notable for their steely directness, sensual dazzle, and portrayal of how lush with possibility late, late life could be. As a widower in his 90s, Angell ran off and got (happily) married for the third time.

He was, for many of us, the model of how to age well. Angell memorized poems to keep his mind limber, and he continued to watch baseball (and hockey!), even as he went blind. By then he had become fully in life the man who’d always lived on the page. You could see it in his attitude toward new technology, which he never resisted.

Email unlocked him: As in his essays, here he was free and open, his best self. Many people received these wondrous missives, written at Mays-on-the-bases speed, including me. As I look back through the profusion, I find him writing the day after my wedding, first to say that it had been declared “rite of the year in this morning’s international polling,” only then to mischievously advise that he was downgrading his wedding gift from Tiffany Spode china to four non-monogrammed hand towels. Time passed, and he was urging me to teach my Little League son to be a switch-hitter: “It’s easy. Just tie his favored hand behind his neck.” When I was soon to take the boy to his first Major League game, Angell wrote, “My granddadly advice is to try not to make it too monumental. Let the kid decide what it means.”

To praise his Christmas poem, which he reprised in 2008 and 2009, was to be accused, by return e-post, of unsubtle lobbying for one Nicholas Dawidoff to be included next time. Then came a yuletide feast of exegesis that I will continue to savor, especially during the holiday off-season, on cold days when I miss my mentor:

This means a lot but probably doesn’t improve your chances of ever making it into the poem yourself—an absolute factor, let’s face it, in these compliments, even though that’s all happening in your unconscious. The challenge, even for a supple, Coleridgean rhymer like me, is that “-off” ending in your handle, since it lends itself mostly to a dumb echo-rhyme (“... my hat a doff” … etc.) but not to much more, since I would never force-rhyme (... “shout huzzahs until we cough ...;” … lift us from despond’s trough ...) etc. etc. etc.

The only solution is for you to change your name, which I hear is really easy once you make the decision. I wouldn’t try to keep any part of your present encumbrance, since “David—” is no bed of roses rhyme-wise, either. I would go for something that’s short, direct and subtly reassuring, even a tad Waspish. I rhymed Senator Claiborne Pell three or four times in my “Greetings” in the ’80s and ’90s, often with the marvelously easy connector-rhyme of ... “as well” or the bonging or cheery combination of “bells” with Senator P. along his wife! i.e. ...

“... something, something, ye Christmas bells,

To elevate the Claiborne Pells.”

I’m spitballing but you get the idea.

Senator Pell is retired and maybe dead now, as well, which leaves a gaping vacancy for anyone bold enough to grab it.

Nicholas Pell

Just look at it. It coruscates, it shimmers in the light. It’s almost a statue. Fame and royalties will swiftly ensue, and poets will come running, including me. I make no promises, of course, but I do admire a man of action.