The Queensland government celebrated the creation of new national parks this year, with Premier David Crisafulli saying it is time to “get serious” and be “ambitious” in protecting nature.

But this claim doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Despite decades of conservation promises, Queensland remains a globally significant hotspot for destroying forests and native vegetation.

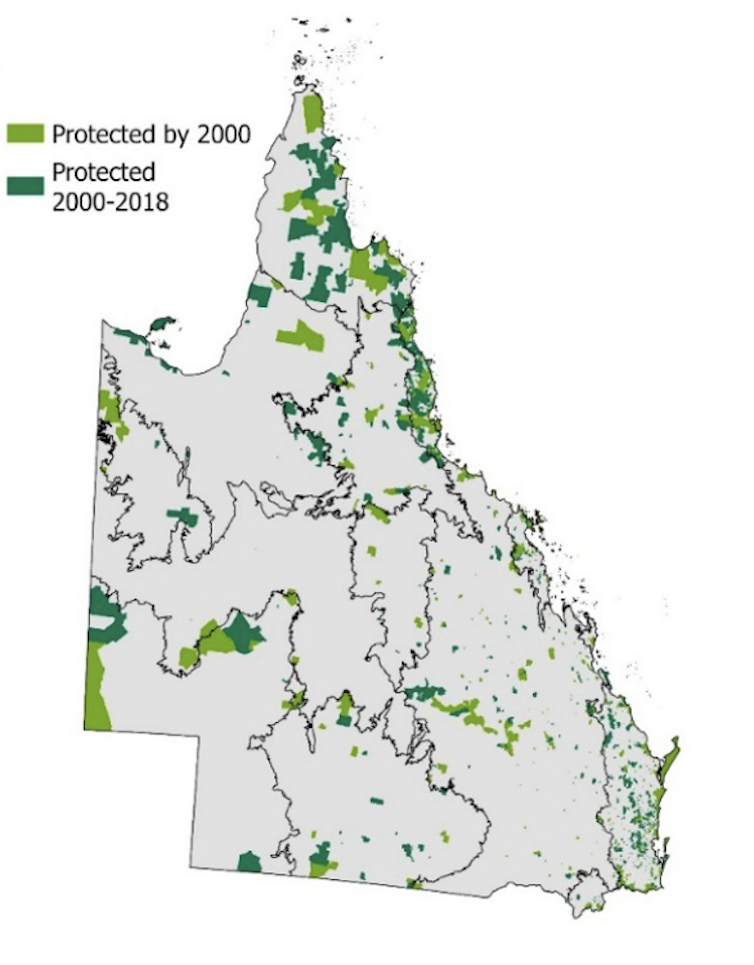

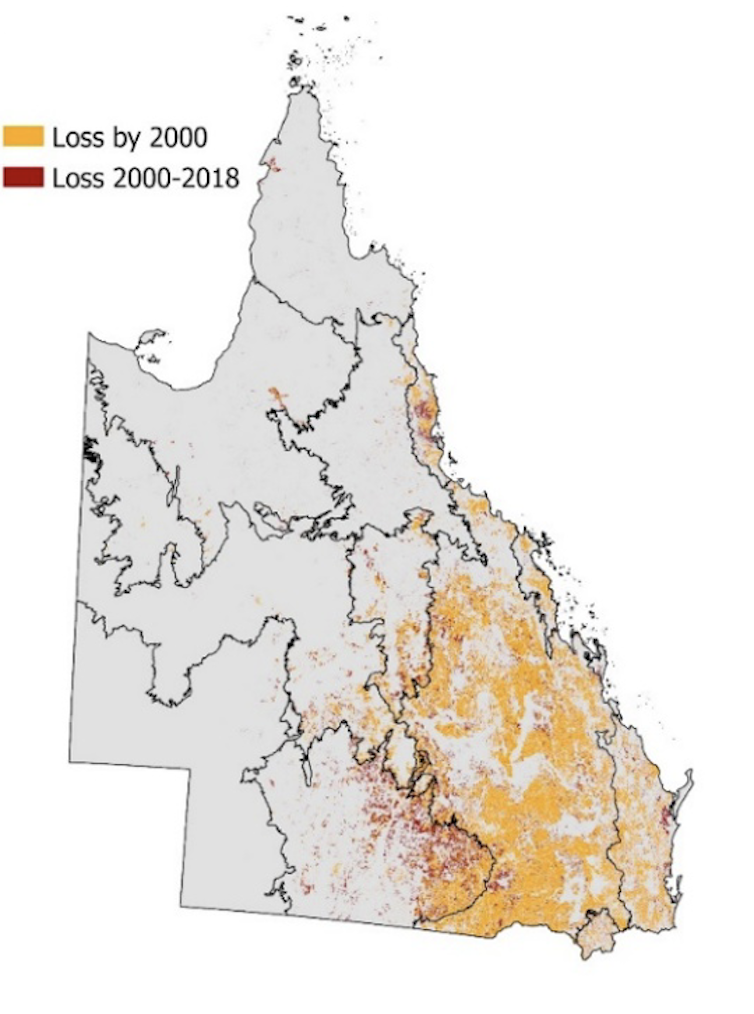

Our new study finds Queensland has lost at least 21% of its original woody vegetation since European colonisation. One-fifth of that loss has happened since 2000, even as the area of land being protected in state or national parks more than doubled.

By 2018, nearly two-thirds of subregions (areas that have similar patterns of climate, geology, vegetation and wildlife) still had less than 10% of their woody vegetation protected. Half were considered at “high” or “very high” risk of further loss.

Despite the creation of new national parks in some areas, bulldozers have kept working across vast parts of the state. Threatened animals, plants and precious landscapes are hanging on by a thread.

Parks in the wrong places

Our analysis compared the loss of forests with the growth of protected areas across all Queensland regions with significant woody vegetation cover, using government data from 2000 to 2018.

This conservation “balance sheet” approach shows not only where protection is growing, but whether it’s keeping pace with ongoing clearing.

We found a dangerous imbalance: for the 20% of vegetation cleared, only about 10% has been protected. And this mismatch was more stark when we looked at different parts of the state.

Most of Queensland’s newly protected areas were in subregions within areas such as Cape York (northernmost point of mainland Australia) and the wet tropics (northeast coast), which already had the highest protection and not under land clearing pressure.

Meanwhile, areas that have historically been heavily cleared kept losing vegetation at some of the fastest rates in the country, with very little new protection added.

These included the Brigalow Belt – a wide band of acacia-wooded grassland between the coast and the semi-arid interior – the New England tablelands in the south of the state, and parts of the Mulga Lands in the south-west.

The illusion of progress

Governments often report the growth of protected areas as evidence of progress toward global targets, such as protecting 30% of land by 2030 under the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

But focusing only on the creation of new parks paints a very misleading picture. If the bulldozing in Queensland continues at current rates, the net outcome for nature is negative, even when more parks are created.

We identified regions of Queensland that are ecological crisis zones and need targeted protection now.

The Brigalow Belt – home to species such as the northern hairy-nosed wombat, bridled nail-tail wallaby, golden-tailed gecko and Brigalow scaly-foot legless lizard – has lost almost half of its original woodland vegetation.

And areas across heavily-populated southeast Queensland continue to be cleared for grazing and infrastructure. These are the landscapes most in need of urgent intervention — not just remote places that look good on international scorecards.

Tougher protection

Stricter limits or moratoriums on clearing in fragile environments could ensure their protection. This will only happen with tougher compliance.

And expanding protection to capture depleted environments, rather than just photogenic or politically-palatable ones, is another way both state and federal governments can act.

Our research also shows an urgent need for a bold restoration agenda. Many of Queensland’s ecosystems are in a perilous state. Incentives and funding are needed for both protecting and restoring habitats where losses are already severe.

From accounting to action

Signatories to the Convention on Biological Diversity, which include Australia, have agreed to halt and reverse biodiversity loss this decade. But as Queensland’s example shows, success depends not just on how much land is protected but on how effectively we prevent nature from being destroyed.

Queensland’s nature protection strategy must move beyond counting hectares of parks. Instead, it should focus on a four tier approach: stopping the destruction of native vegetation, restoring degraded land in areas that provide a biodiversity benefit, ensuring protection targets important areas for biodiversity, and an accounting system that is transparent and captures both losses and gains.

Otherwise, we can only expect more of the same: a small jump in the number of protected areas in politically palatable locations and far less protection for the animals and plants that looking down the barrel of extinction.

Michelle Ward has received funding from the Australian Research Council, National Environmental Science Program, Queensland's Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland Conservation Council, Australian Conservation Foundation, The Wilderness Society, and WWF Australia.

James Watson has received funding from the Australian Research Council, National Environmental Science Program, South Australia's Department of Environment and Water, Queensland's Department of Environment, Science and Innovation as well as from Bush Heritage Australia, Queensland Conservation Council, Australian Conservation Foundation, The Wilderness Society and Birdlife Australia. He serves on the scientific committee of BirdLife Australia and has a long-term scientific relationship with Bush Heritage Australia and Wildlife Conservation Society. He serves on the Queensland government's Land Restoration Fund's Investment Panel as the Deputy Chair.

Ruben Venegas Li has received funding from South Australia's Department of Environment and Water, Queensland's Department of Environment, Science and Innovation as well as from Wildlife Conservation Society, Queensland Conservation Council, and The Wilderness Society.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.