Corruption in the Catholic Church long predated the eight-year papacy of Pope Benedict XVI, which began in 2005. The Protestant reformers hammered their critique of Catholic greed and treachery into history several centuries before this pope. The churn of time proved no cure for the Church’s failings. When Hannah Arendt published her reflections on the life and death of Pope John XXIII in 1965, she hung her consideration on the questions posed to her by a canny Roman chambermaid: “Madam, this Pope was a real Christian. How could that be? And how could it happen that a true Christian would sit on St. Peter’s chair?” After so much worldly infamy, the idea seemed suspect.

But the rot the world learned of during Pope Benedict XVI’s tenure was new in its overwhelming attestation from victims, its global reach, and its especially sinister perversion: For decades, priests and prelates had raped and sexually molested thousands of children in their charge, and their superiors in the Church had protected them from consequences, allowing the abuse to continue and spread unabated.

Although sex abuse in the Church appears to have been most rampant from the ’60s through the ’80s, discovery of widespread mishandling of sex-abuse cases came about in 2002, with The Boston Globe’s coverage of crimes in the Archdiocese of Boston. Benedict XVI was therefore left to reckon with a groundswell of reports recounting hideous violations that had taken place before he was pope but during his long career as a prelate. There was the Ryan Report of 2009, which identified hundreds of cases of sexual and physical abuse perpetrated in Catholic institutions in Ireland from 1914 to 2000; the Murphy Report, published later that same year, which found evidence that more than 170 priests in the Archdiocese of Dublin had been shielded from allegations of sexual abuse from 1975 to 2004; and, finally, The New York Times’ exposé of the American priest Lawrence C. Murphy, who sexually abused boys at a school for the deaf in Wisconsin for decades despite his victims’ best efforts to have the man stopped, including, in 1996, through the appeal of an archbishop to then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. Ratzinger, at the time of the report’s publication in March 2010, was no longer Cardinal Ratzinger at all; he had become Pope Benedict XVI.

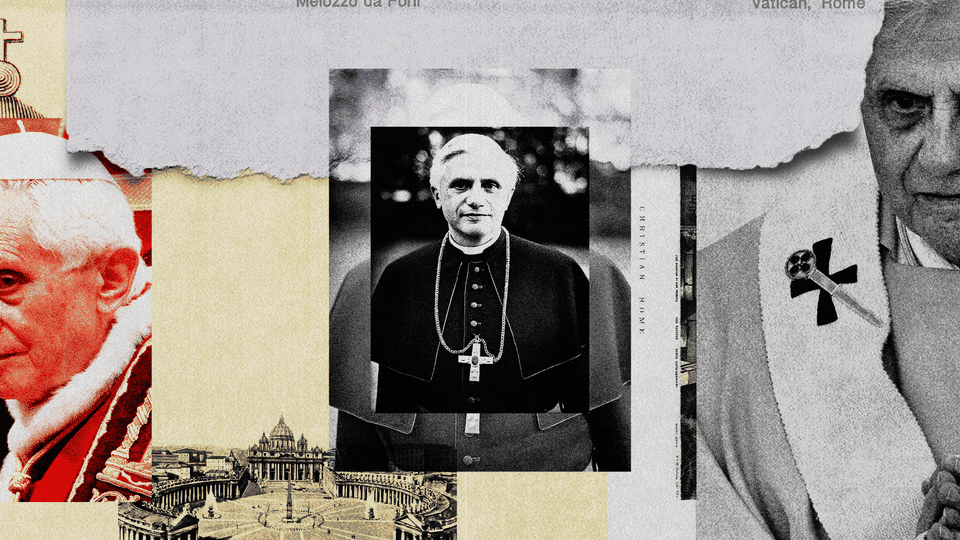

Thus, the face of the Catholic Church when much of the world decisively lost faith in the institution was his. An aged face: Somewhat withdrawn and intellectual, already white-haired and occasionally bespectacled upon his election, Benedict XVI was never the charismatic, crowd-working celebrity that John Paul II had been, nor did he have the simple, common touch that Francis would bring to an office so badly in need of moral credibility. Instead, Benedict XVI was devoted to his theological work and, perhaps even more so, to the otherworldly beauty the Church lays such proud claim to: “Better witness is borne to the Lord by the splendor of holiness and art which have arisen in the community of believers,” he once wrote, “than by clever excuses which apologetics has come up with to justify the dark sides which, sadly, are so frequent in the Church’s human history.” The late pope emeritus’s reputation as a liturgical traditionalist is thoroughly entangled with his record as an advocate for sacred artwork and music. Though I understand that the politics of the two camps are rather opposed, I find their means and methods suspiciously similar: Both are compelled to the best versions of themselves by beauty. Benedict XVI himself seemed to hail every kind of beauty—he reintroduced several retired items of papal attire during his tenure, and wore a bespoke cologne with notes of grass and verbena—but this often seemed to only aggravate public sentiment against him, perhaps because he led the Church at such an abhorrently ugly time.

Evidently, the tension weighed on him. Peter Seewald, a German journalist and Benedict XVI’s biographer, writes in his second volume on the pope emeritus that, in the later years of his papacy, the pontiff “felt a sense of gloom … No Catholic would ever think Christ’s community could be purely holy, all wheat and no weeds. But the older he became, the more he doubted that human beings would ever learn. ‘But let’s leave that,’ he once abruptly ended a discussion, when he was asked about his hopes for the future.” In the aftermath of the sex-abuse crisis and the 2012 “Vatileaks” scandal, in which a trove of internal Vatican documents were published depicting a corrupt and altogether worldly struggle for power and influence in Rome, then-Pope Benedict XVI apparently began to withdraw. He knew the feeling, Seewald writes, “of no longer being equal to a situation.”

And so, it was the corruption in the Church, always an item of ridicule but now a pervasive, agonizing reality, that seemed at last to overshadow the man, who became in 2013 the first pope in 600 years to retire from his office. The pope—who in 2010 had remarked, dispiritingly but not unconvincingly, that “humanity has succeeded in unleashing a cycle of death and terror which they can no longer break out of”—became the pope emeritus, and left the Roman Catholic Church and its billion souls in the hands of his successor, who has typically struck a more optimistic note.

The wisdom of that insight aside, it is hard to disagree with Benedict XVI’s own assessment that he was in some sense unequal to the moment, not least because the conclusion squares with the gravity of the crisis itself. This was and is the sort of darkness not seen for centuries, a historic catastrophe. It affected its direct victims, their families and loved ones, the parishes and dioceses that became responsible for settling with them, the parishioners who now had to salvage their faith. The world—and the Church—post-crisis can feel like a place too violent, too exploitative for the vulnerability of enchantment. Perhaps the pope emeritus saw the magnitude of the damage himself, and perhaps his retreat came nearest to acknowledging it.

How heavy the toll is—how it colors the Church’s recent history with a streak of predatory menace, how it demands an accounting for itself even in moments of celebration and loss for the Church, how it irrevocably complicates simple lay faith. The summary Catholic novel of the post-crisis era may well be Mary Doria Russell’s prescient The Sparrow, whose protagonist cries out before a council of his brother priests: “I had nothing between me and what happened but the love of God. And I was raped.” To speak of the Church now is always to speak after the crisis; to write about the faith now is always to grapple with this ghastly inheritance. But where there remains something whatsoever to be said, there remains some hope, and some capacity for redemption. That belief may at last be the very one upon which the entire faith survives.