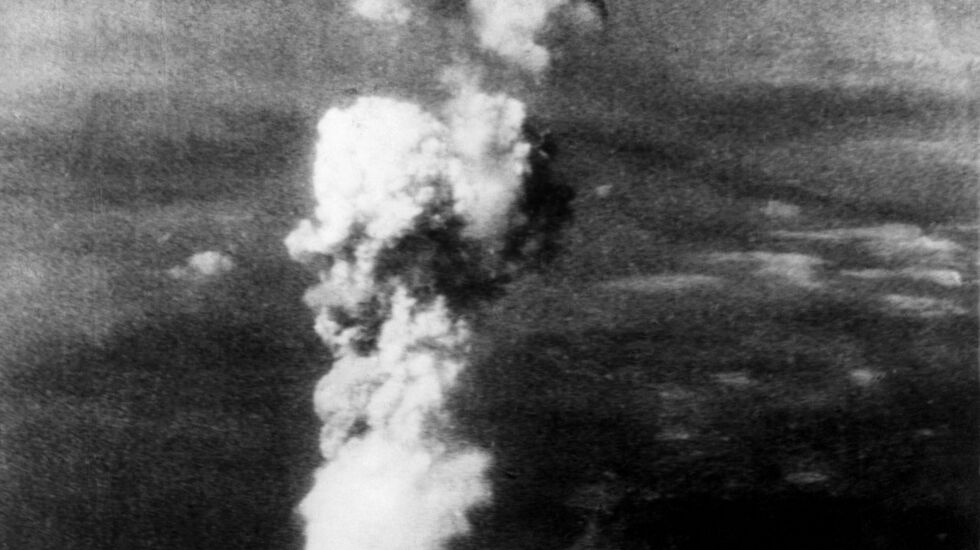

This weekend’s anniversary of the end of World War II, coming at a time when we continue to talk heatedly about the film “Oppenheimer,” reminds me of how long I showed images of the Hiroshima mushroom cloud to introduce class lectures on wartime Japan. They were dramatic; they evoked power; they were horrific. And students loved them.

I could have used other images. I might have shown a photo of a man I met in 1979 at the Hiroshima bomb memorial. Standing with his daughter in front of thousands of peace cranes, he told me she was 34 but had the mind of an 8-year-old — because she was born on the day the bomb was dropped. Her mother died, and she survived.

Or I could have talked about Dr. Michihiko Hachiya, who saw a flash on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, after a night’s work in a Hiroshima hospital. He jumped up to go outside and find what caused the flash. When he looked down, he saw that his clothes had vanished; he was naked.

But I preferred the cloud image because it attracted students.

In later years, my attraction to that image waned, however, as I saw how it over-simplified the bomb, capturing its power but not its tragedy. I largely stopped showing it.

After seeing “Oppenheimer,” I have become more certain than ever that we must begin looking at the bomb — at all nuclear weapons — in a more nuanced and honest way if our world is to remain livable.

When we hear the father of the atomic bomb say, “All war becomes unthinkable,” when we see him grapple with what he produced, we should be warned about the danger of accepting the easy-to-chew narratives that still shape our understanding of Hiroshima — and of nuclear weapons today.

The decision to drop the bomb was not, as President Harry Truman suggested, a simple one. Nor did it represent any consensus that 1 million American GIs would die if an invasion of Japan were necessary. Estimates of how many Americans would be killed in fighting on Japan’s mainland varied greatly in discussions about whether to use nuclear weapons, but most military experts then put the losses in the tens of thousands. The million figure became “truth” only when Secretary of War Henry Stimson introduced it in a 1947 Harper’s magazine article.

There also were disagreements about whether the bomb should be used at all. The debates were fierce, with Stimson expressing doubts and Secretary of State George Marshall opposing the use of nuclear weapons against civilians. Fleet Admiral William Leahy called them barbaric.

And there was sharp disagreement about whether atom bombs even were needed to make Japan surrender. Today’s historical consensus is that Japan would have surrendered by the end of 1945, regardless. After the war, President Dwight Eisenhower said he had argued against dropping atom bombs because Japan’s defeat already was assured. We already had killed enough Japanese with regular bombs — nearly 90,000 on a single March night in Tokyo, for example — to make continuation of the war next to impossible.

The decision to open the nuclear age was understandable. Wartime invites costs-be-damned thinking. But such thinking in this case unnecessarily opened the door to the possibilities that frightened Oppenheimer — possibilities that could quite literally end human civilization.

That being the case, we must look at the war-driven language that saturates our discussions of Europe and Asia today.

We continue to be told that Ukraine has no choice but to fight until the Russians are driven out yet hear almost nothing about the more honest and complicated truth: That the only way to avoid endlessly continuing deaths and destruction is through negotiations.

On the other side of the globe, our officials toss around confrontational language about China, labeling Xi Jinping a “dictator” and threatening to employ “all” military options, with no discussion of the devastation that would result if we stumbled into war with nuclear-armed China.

People are right to condemn Putin’s aggression and Xi Jinping’s threats against Taiwan. But the short-sighted, war-fogged thinking that brought us Hiroshima still dominates our discussions of Ukraine and eastern Asia. This time, however, it is a world stocked not with two small bombs but 10,000 massive nuclear weapons.

One only wishes Oppenheimer had been right when he pronounced war unthinkable in a nuclear-armed world, a world that could be destroyed before climate change even gets its own chance to do so.

Chicago resident James Huffman is the Hirt Professor of History emeritus at Wittenberg University. He has published nine books, including “Japan in World History.”

The Sun-Times welcomes letters to the editor and op-eds. See our guidelines.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Chicago Sun-Times or any of its affiliates.