As part of her ongoing public art series, Pax Americana, Toronto visual artist Dara Vandor has been posting aluminum signs in public spaces.

These are plaques that reimagine, as the artist writes, the city as “a site of future conflict and occupation” by the United States. The signage, in the style of commemorative historical markers, echoes U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent and repeated threats to annex Canada and “is meant to serve as a dark warning, inviting contemplation on the fragility of nationhood.”

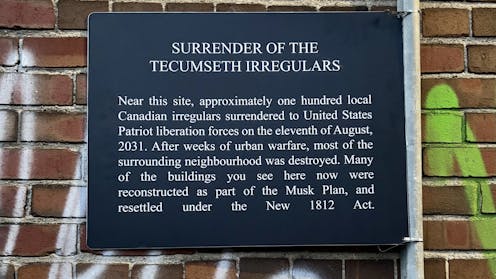

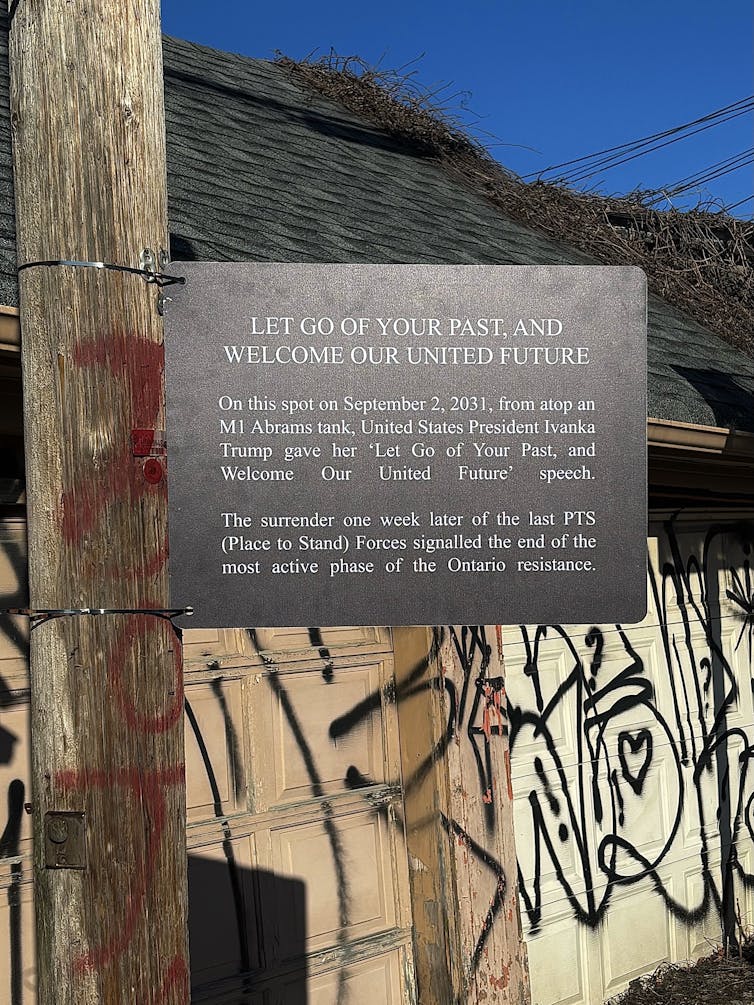

For example, one plaque, posted on a bridge on Spadina Ave., informs passersby:

“This spot served as the center of operations for United States Army snipers during Operation McKinley, the campaign to liberate the northern territory formerly known as Canada. From February to May 2035, this site, code-named ‘The Hot Dog Stand,’ served as a concealed sniper’s nest, providing precision fire support, disrupting insurgent movements, and protecting advancing American units.”

Vandor’s thought-provoking project, which she told CBC News was sparked by anger at Trump’s threats to Canadian sovereignty, underlines how storytelling can be a powerful tool in times of conflict, especially when it affords itself the artistic freedom to envision potential futures before they can become reality.

Psychological effects

In order to understand how exactly stories such as the one portrayed on Vandor’s plaques can make a real impact on the way we navigate moments of crisis, we can turn to the work of conflict analysis experts such as Solon Simmons.

In his recent book on conflict storytelling, Simmons introduces the concept of post-plot pressure.

The term describes the psychological effect that a story can have on its readers after they finish reading. As Simmons puts it:

“What makes stories so important (as opposed to just interesting or entertaining) is the effect of the story, and this effect doesn’t end when the story ends. It leaves the viewer/reader/listener with a feeling.”

Simmons also explains that the kind and amount of post-plot pressure placed upon an audience depends on the type of story being told.

Projected unhappy ending exerts pressure

A story, for example, featuring a struggle in which the antagonist eventually triumphs over the protagonist is what Simmons calls a “satirical struggle story.”

“Satirical” in this context does not necessarily mean that stories of this kind include elements of mockery or sarcasm. Rather, the label goes back to the influential research contributions of Canadian literary theorist Northrop Frye and American historian Hayden White, from which Simmons derives his own framework.

This is exactly how to understand the story told over its several episodes on Vandor’s Pax Americana plaques: the U.S., as the story’s antagonist, abuses its power and ends up getting away with it, defeating Canadian resistance and annexing what is now only referred to as the “northern territory.”

As Simmons suggests, conflict stories like this one, where what is viewed as injustice is allowed to prevail, exercise a relatively high level of post-plot pressure. This is mainly because the unhappy ending leaves audiences dissatisfied and with a sense of loss to grapple with.

Reader reactions

Simmons also explains that not all readers react to this particular kind of post-plot pressure in the same way. Vandor’s project, for example, has brought out some critical and upset responses.

As the artist told Toronto Today, some people have called the plaques pro-American propaganda; one online commenter said they should be taken down.

Julian Bleecker — a researcher, author, designer and engineer with a PhD in history of consciousness whose design studio offers services around future imagining and planning — voiced his objection to the project in a blog post.

In his opinion, the antagonistic and fatalistic vision of the future portrayed on the plaques runs the risk of “playing into the hands of the very forces that are at work to make the world a less habitable place.”

Read more: The theatre we want in 2040? We used 'strategic foresight' to plan on the Prairies

But, as Simmons argues, conflict stories in which the happy ending never comes can also leave readers with a productive sense of post-plot pressure. In that case, feeling dissatisfied with the story’s outcome can instead motivate people to mobilize and strategize against the perceived injustice.

Seen in this light, the plaques’ imagined collapse of Canadian sovereignty can therefore also serve as a stark and urgent inspiration, begging response.

A cautionary tale

Fictional storytelling is often viewed as a useful tool that allows us to make sense of real moments of conflict that happened in the past. Think, for example, of Erich Maria Remarque’s famous war novel All Quiet on the Western Front, which was turned into an Oscar-winning film directed by Edward Berger in 2022.

Our understanding of these kinds of stories as useful comes with the acknowledgement that there is nothing we can do to prevent past conflict. At the same time, the underlying assumption here is that by learning about the past, we can learn from the past and hopefully stop similar crises from ever happening again.

What makes Vandor’s ongoing project especially valuable is that it moves its reflections on the past into an imagined future. The actual conflict that the plaques refer to is still part of the present, and its future still undecided. Whatever lessons we draw from their cautionary tale about Canadian annexation, we still have time to act upon them before that imagined future can become reality.

Importance of resistance in the present

This is exactly what leads historian Camille Bégin to conclude that the project’s appeal to the importance of resistance in the present is particularly strong:

“It really shows us that the future is not written, that it’s in our hands to act in the present to forge the future that we want.”

Even though Vandor’s project tells a story of Canadian defeat, it also highlights that Canadians did resist, a thought that should appeal to anyone opposed to Trump’s vision of territorial expansion.

Or, and this is perhaps the most hopeful reflection coming out of the project, if Canadians come together and resist now, Trump’s threat of annexation may never get that far.

Pascal Michelberger does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.