For a long stretch of Earth’s history, the continents were not separated by wide oceans. They were joined into a single landmass known as Pangaea. It formed slowly, through collisions that took place over tens of millions of years. There was no clear starting moment. Land simply kept drifting together until separation was no longer the norm.

Pangaea existed long before humans, mammals, or even flowering plants. In geological terms, it was stable for a while, but it was never meant to last. Once the continents were locked together, the planet worked differently. Huge areas of land lay far from the ocean. Rain struggled to reach the interior. Temperatures swung more sharply between seasons. Some regions baked. Others froze.

This was not a world with gentle gradients. Coastlines were limited. Deserts expanded across central areas. Forests survived mostly near the edges. Ice came and went at different times, depending on global conditions. Much of what is known comes from rock layers and climate models rather than direct evidence.

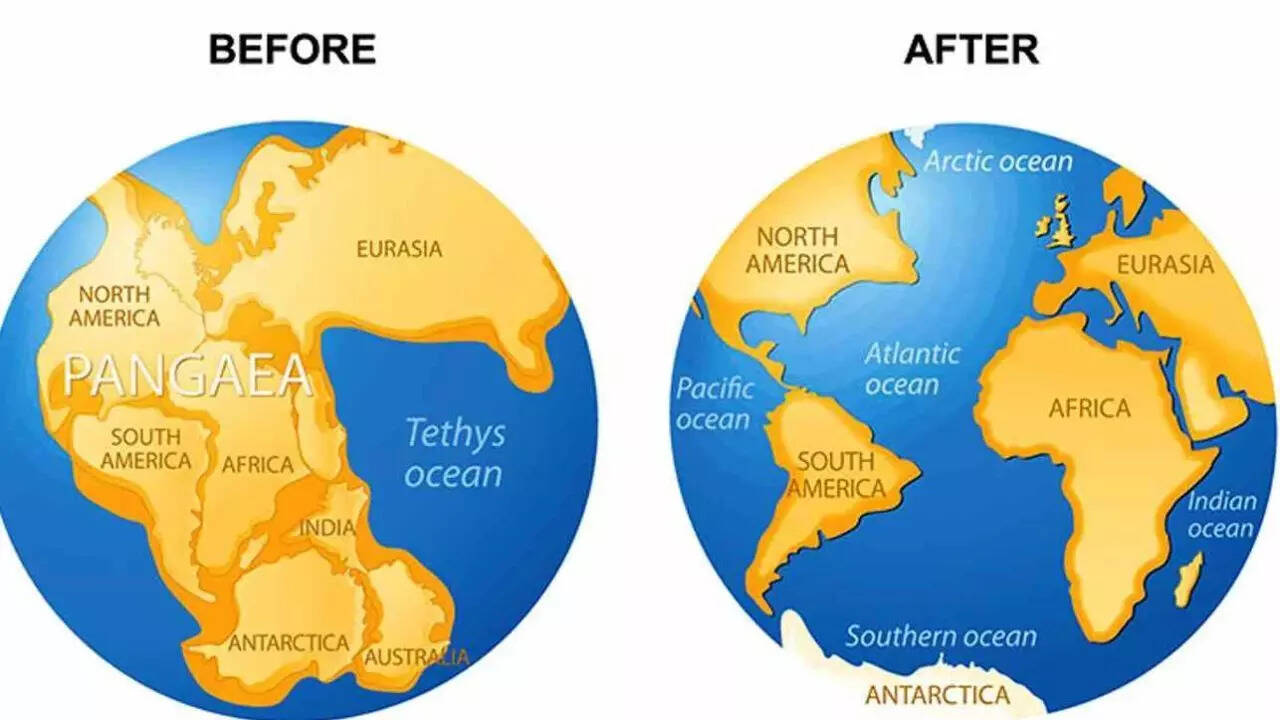

Earth’s continents were once joined as Pangaea before they moved away

With no oceans in the way, plants and animals could move across vast distances. This is why similar fossils appear today on continents that are now thousands of kilometres apart. Reptiles, early mammals, and ancient plants left traces across what are now separate worlds.

But access did not mean comfort. Many regions were harsh. Life clustered where conditions allowed it, and vanished where they did not. Survival depended less on mobility and more on tolerance. Pangaea did not simply split apart without warning. Heat accumulated beneath the thick continental crust. Weak points developed. Volcanic activity increased along fractures. Over time, the land began to stretch.

Cracks widened. Valleys formed. Eventually, water filled those spaces. New oceans began as narrow seams before expanding. The breakup was slow, uneven, and irreversible once it reached a certain point.

The breakup reshaped Earth’s long-term climate

As Pangaea fragmented, coastlines multiplied. Ocean currents shifted. Moist air could once again move inland. Rainfall patterns changed. Some deserts shrank. New ecosystems appeared.

These changes did not happen all at once. Species adapted, migrated, or disappeared. The world became more fragmented, but also more climatically diverse. This set the stage for the rise of many modern ecosystems.

Pangaea still leaves marks on today’s planet

The influence of Pangaea did not end when it broke apart. Mountain chains line up across oceans. Rock layers match across continents. Even the shapes of coastlines hint at how the land once fit together. Geologists see Pangaea as part of a cycle, not an exception. Supercontinents form, break apart, and eventually form again. The plates are still moving.

Pangaea is often described as ancient history, but it is better understood as a reminder. The continents feel permanent, yet they are temporary arrangements in a much longer story that is still unfolding.