We’ve been fighting nature for years. Given climate change, it’s high time to let rivers roam. David Williams reports.

Chris Allen apologises for not being able to speak earlier.

“I was trying to get some lambs dagged, and it was getting wet and cold and dark and horrible.”

There seems to have been a lot of wet and cold, of late.

Allen’s sheep, beef and arable cropping farm, Annadale, spans some 360 hectares – just over twice the size of Christchurch’s Hagley Park. The farm is where Bowyers and Taylors Streams meet, and then join the south branch of the Hakatere/Ashburton River. Hence the area’s name: Ashburton Forks.

In May last year, flood waters gushed across a quarter of Allen’s farm, collecting fences and culverts, damaging and drowning machinery, and spreading trees, rocks and gravel. The flood scalloped a hole in the farm’s 6.5-hectare irrigation pond, and left a 75cm-deep layer of sediment.

(The total, regionwide recovery work after the flood is estimated by the regional council, ECan, to cost $20 million, $7.5 million of which will be paid by the National Emergency Management Agency because of its regional significance.)

That’s about 20,000 tonnes of sediment which, now, thanks to the fastidious work of diggers and dump trucks, spread over a five-hectare block the flood blew through. “Over time that will just settle down,” Allen says. “It has got grass on it now.”

Traces of flood damage might have been erased at Annadale but the threat lingers, as evidenced by storms in recent weeks.

After last year’s damage, Allen says the regional council scooped gravel from the bed of Taylors Stream in one spot, “just to shore things up”. “And you look at it now and you go, holy shit, that’s all filled up with gravel.”

At another spot, just above the farm, the stream, spurred on by heavy rain and snow melt, ran incredibly high a fortnight ago. Another nightmare was avoided by just 100 millimetres.

“The water was spilling in, but it didn't have enough depth to do any more damage,” he says. “We’re really, really vulnerable.”

In a climate crisis, Ashburton Forks doesn’t hold a monopoly on vulnerability.

Think about Westport. Edgecumbe in 2017. Or the rain-drenched North Island in March. In November last year, Gisborne received more rain than in a single day than it did for the whole of the previous summer.

Around the world, the mercury hit 40C in England, and, in January, 50.7C in Western Australia.

A year ago, after killer floods in Europe, a group of concerned scientists said the question was no longer whether global warming — caused mainly by the use of fossil fuels — will influence the occurrence of extreme weather events, but “in what way and to what extent”.

Back here, scientists found last year’s Canterbury floods were 15 percent more intense as a result of our warming world.

As NIWA meteorologist Chris Brandolino explained after record rain in March: “In the future, it’s likely such events will become even more common and more extreme.”

Given the extra energy in our already boisterous rivers, building higher floodbanks isn’t going to work, in many cases.

There are calls for a re-think. And in some areas, at least, the revolution, of giving the rivers room to roam, is already underway.

The Canterbury Plains were created by high-energy, braided rivers blasting down slopes between the Southern Alps and the coast, hopping between ancient channels and new ones, forming huge, gravel fans.

Colonised New Zealand has gone to great lengths to try and tame nature, impounding rivers behind banks so floodplains can be developed. Not that it always worked. As former Prime Minister Geoffrey Palmer famously said, Aotearoa is an “irreducibly pluvial nation”.

Human-induced climate change makes extreme weather events more likely, but the way we manage rivers is making matters worse.

“You’d now call it mismanagement,” says Gary Brierley, a Professor of environment at University of Auckland.

Essentially many of our rivers have been strangled, disconnected from their historic channels and confined to smaller areas by engineered flood defences. This has led many riverbeds to build up, or aggrade, considering the huge volume of gravel and sediment being transported from the mountains to the sea.

It has also given people hope, falsely in some cases, that they’ll be safe, pushing development closer to rivers, and within their historical range. Should the worst happen, then, the repair bill for damaged infrastructure and developed property rises, not to mention the risks to lives.

“We are manufacturing future disasters,” Brierley says. “We have created the circumstances by which this is happening.”

Flood periodicity – how often they recur – is changing. Giving them less space ramps up their power, Brierley says.

Another factor is society’s disconnection. “We just perceive the river to be ‘over there’; we’re not living with it.

“And it’s just a disaster waiting to happen because many of our rivers are now perched higher than their floodplains, whether it’s in the Tukituki and rivers around the Ngaruroro, or rivers down in the Wairarapa and the Ruamāhanga, rivers like Ashburton, or rivers in Canterbury plains that just simply want to re-occupy the bits of the old riverbed that they used to be in.”

Brierley’s colleague at University of Auckland, Dan Hikuroa, a senior lecturer in Māori studies, says when a river floods “it’s a river being a river”.

In Te Ao Māori, the Māori world, rivers are seen as ancestors, and you can derive part of your identity by your connection with it. As proved by generations of Māori observation, those ancestors can meander across a landscape.

One way to explain this behaviour is through purakau – knowledge in story form. Māori might say, Beware the flicking tail of the taniwha (dangerous water spirit), to explain disaster risks in certain areas.

“If we actually listened to the way rivers behaved, and observed their natural fluctuations and observed seasonal things, and also looked out for the critters and things that live in rivers, in our conceptual design, those are the many voices of the river that are speaking to us,” Hikuroa says.

“Sometimes those voices are absent and sometimes those voices are silenced.”

Jonathan Tonkin, a senior lecturer in population and community ecology at University of Canterbury, says from an ecological standpoint, the more space you give a braided river, the more naturally it functions.

That creates variability and heterogeneity in habitat. Water rocking and rolling in riffles and rapids, bubbling up through springs, and sinking into swimming holes, makes homes for a wider variety of species.

Constraining a braided river’s complexity with, say, rock revetments, groynes and concrete walls, and choking multiple channels into a single channel, speeds it up, removing species and strangling biodiversity. (There’s the other worldwide crisis we hadn’t mentioned yet.)

“Disturbances are fundamentally important, a natural thing in ecology,” Tonkin says. “It’s something that all of our native species are adapted to.”

Black stilt/kakī often nest on islands in the middle of braided rivers, away from predators, and hide their camouflaged eggs among the gravels. The threatened Robust grasshopper, with what looks like armour plating, is endemic to riverbeds and terraces in the Mackenzie Basin.

Take away a river’s natural character and our fish, birds, macroinvertebrates, tuna and īnanga struggle, or disappear.

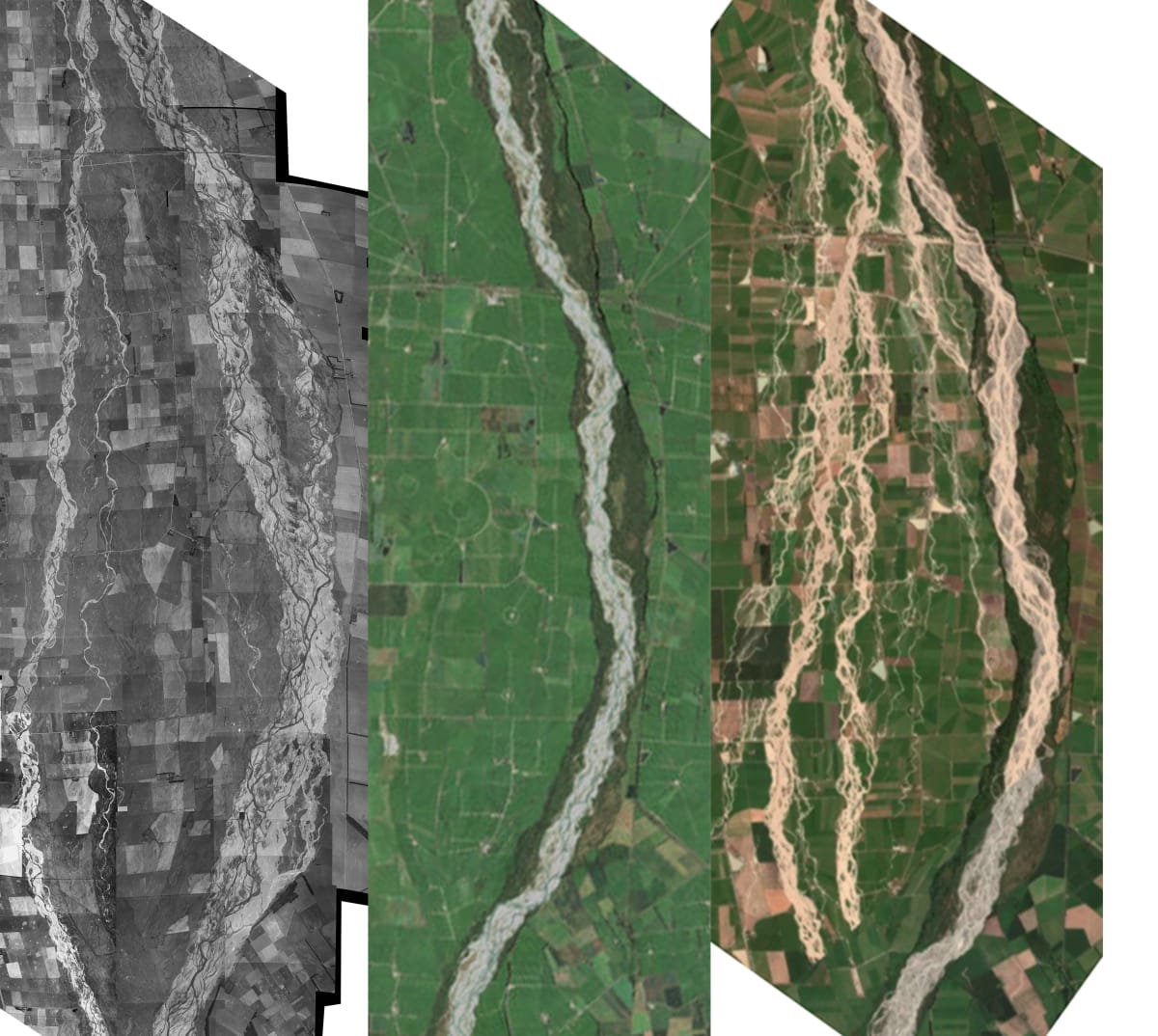

At a braided rivers conference at Lincoln University last month, Forest & Bird freshwater advocate Tom Kay showed aerial photos of constrained rivers, compared with their natural range. He says Canterbury is the poster-child for river encroachment.

Yet people are still surprised when rivers burst their artificial banks. “The river’s going to take back that room whether we like it or not,” Kay says.

“What we’re doing isn’t working for ecology or ecosystems or community resilience, and we need to do something differently.”

Forest & Bird says we need to make room for our rivers, something the Dutch know a lot about.

During most of the 20th Century, Netherlands managed to escape major riverine floods. (Although, a 1953 storm caused the surging North Sea to breach dykes, killing more than 1800 people.) Near-misses in the 1990s spurred its people into action.

The biggest was in 1995, when 250,000 people and a million cattle were evacuated. But no dykes were breached, and no one died.

“Our system was not safe enough,” says Ralph Schielen, a water management expert at the Netherlands’ Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. “We had to do something.”

The response became known as Room for the River, for which Schielen became an adviser on hydraulics and morphology.

Effectively, there was too much water for the barriers to handle. The water needed more space to flow, wider areas to meander, and to be slowed through natural sponges.

The Government directed 39 related projects to be built, with the on-the-ground details to be decided by local and regional authorities and communities. The result was new flood by-passes, expanded flood plains, relocated dykes, and lower groynes. (Room for the River was controversial, sparking protests and court challenges.)

Completed in 2018, the project cost €2.3 billion.

Did it work? Schielen says flood levels since have not hit 1995 levels “but we are quite confident that it will work”. Other benefits include the beautification of river areas, enjoyed by more people, and a marked increase in biodiversity.

Many Netherlands’ rivers are constrained, and have been for centuries. Removing banks and letting them meander again is out of the question. The same can’t be said for some New Zealand rivers.

“If you have the possibility and if you have the space, and if there is not so much economic activity in the floodplains, then I would always say try to maintain that space and try to keep the river as natural as possible,” Schielen says.

“You should work along with the river and not against it.”

Just getting started

Despite the Te Ao Māori view, getting people out of nature’s way in New Zealand is embryonic.

The country’s first attempt at managed retreat, in the Bay of Plenty town of Matatā, has been traumatic for some residents.

In the Hutt Valley, north of Wellington, meanwhile, 120 properties are being bought for the $750 million project called Riverlink, giving more room for Te Awa Kairangi/Hutt River breathe, at the cost of 120 properties, plus new transport links and a new river park.

Once flood protections are upgraded, the surrounding area will be protected from a one-in-400-year flood.

“The alternative is wet feet,” Greater Wellington Regional Council chair Daran Ponter says, while pointing out the Wairarapa faces similar issues. “There’s no getting around it. If you don’t do these works, you’re going to flood whole communities and the consequences of that are dire.”

The national conversation about flood defences seems frayed, and money seems at the heart of it. After all, flooding is this country’s most frequent natural hazard. And with sea level rise and vertical land movement, some areas are more vulnerable than others.

The Insurance Council made a detailed submission to the draft national adaptation plan in June. The country needs to get serious about reducing flood risks, chief executive Tim Grafton says.

“Insurance remains readily available and affordable for New Zealanders in flood-prone areas. But the point that we are making is that New Zealand can’t sit on its hands and do nothing.”

Consents for developments in high-risk, flood-prone areas need to stop now, Grafton says. “Then we need to be identifying higher-risk areas.”

In April, a report from regional and unitary councils, called for central government help to pay for flood protection schemes. The councils spend about $200 million on flood protection, but that falls short of what’s required by $150 million a year.

As part of the Government’s $3 billion Covid-19 infrastructure fund, $210 million was earmarked for “climate resilience and flood protection projects”.

How was that “urgent” request received?

Doug Leeder, who chairs the Bay of Plenty Regional Council, and represents the regional sector on Local Government New Zealand, says the Government acknowledged the issue but, given budget constraints and financial demands, said it wasn’t in a position to address it.

The regional sector will push the Government to establish an annual fund for flood protection work.

Does New Zealand need a flood management agency?

Ponter, the Greater Wellington chair, says: “We certainly think that there is a gap. If you look through the lexicon of government agencies, you’d be hard pressed to find the agency that’s responsible for flood management, flood control, etcetera.”

Bay of Plenty regional council chair Leeder is using what is, by now, familiar language.

“You won’t build your way out of this, in terms of keeping lifting stop banks up,” he says. Some houses and infrastructure will need continued protected but, to some degree, “you’re going to have let rivers find their own course”.

Leigh Griffiths, rivers manager for Canterbury’s regional council, ECan, says giving rivers more room to move has been an “active conversation” within its walls for years, and it is now “actively talking to central government” about permanent co-investment.

ECan is scoping a 200-year river strategy which will cover many topics, including ‘room for the river’, Griffiths says. “The document has not yet been drafted, but the target date for completion is currently June 2023.”

New Zealand seems on the cusp of quite a different style of water management, beyond stopbanks and strangling rivers, but it’s going to take money and leadership.

Newsroom asked several Ministers if a flood management agency has been discussed, and for the Government’s reaction to councils’ urgent call for flood protection money.

Emergency Management Minister Kieran McAnulty said in an emailed statement: “The Government is assessing what more support may be needed including for flood protection – this is a regional council responsibility but we acknowledge there may be cases where central government support is required. And we are considering these.

“Climate change is causing more severe weather events and the resilience of our infrastructure is being tested.”

Even more reason to do something about it, Forest & Bird’s Kay says.

“We’re going to see our infrastructure damaged more often, and it’s going to cost us more, and we’re going to be repairing it perpetually.”

There’s not a single solution, he says. Some stopbanks will be non-negotiable – they have to stay. In other places, regular flooding will lead to honest conversations about the sense of spending money on works in high-risk areas of a floodplain that are doomed to fail again and again.

In that case, a community can come together to solve the problem, including conversations about compensation.

“There'll be places where there's low hanging fruit, where councils already own land alongside rivers, or where there's parks and sports fields and things like that, that can afford to flood from time to time, to completely different scales,” Kay says.

“The way to protect our communities and protect the environment and restore nature is actually to work with rivers rather than sort of continuing to try and fight them.”

Brierley, the University of Auckland professor, says flooding issues will become more expensive the more they’re pushed aside – “because you’re just creating the prospect of bigger and bigger disasters”.

“We can no longer ignore it.”

The head-scratching reality is we know a great deal about how our rivers behave, but, often, authorities and developers are burying their heads in the river sediment, in what seems to be a dangerous game of denialism. The whole lot – our command and control mentality, our relationship with rivers, and the institutions that look after them – isn’t fit for purpose, Brierley argues.

“We just need a different set of relationships and a different set of institutions, to take us to a different place in the ways that we look after these things.”

Back at Ashburton Forks, farmer Chris Allen recalls the “good old days” of the Ministry of Works and catchment boards, when the Government contributed most money towards river protection works, including building stopbanks.

Nowadays, special rating districts collect money from those who benefit.

Allen argues the country is criss-crossed with important infrastructure – roads, bridges, power lines, and internet cables – so we all benefit from flood protection works, even if that means public money being used to buy private land better used to let rivers roam.

“It’s about having a plan, and the plan needs to be facilitated by central government,” Allen says. “But also put some cash aside because it’s going to need some cash.”