The new Tiaho Mai mental health inpatient unit at Middlemore Hospital is the benchmark facility in the country. Newly released design guidelines for future builds will hopefully ensure its successes are replicated elsewhere, reports Oliver Lewis in part four of a series on mental health units in New Zealand.

At the apex of the inner wall of the wharenui, right up the top under the sloping lines of the roof, is a carving of Tama-nui-te-rā, the personification of the sun in Māori mythology.

Service users, or tangata whaiora, are welcomed onto Tiaho Mai, the new acute mental health inpatient unit at Middlemore Hospital, in the wharenui with mihi and karakia. For Māori, the familiar cultural rites help make them feel safe. But, as Te Teira Rawiri — a kaumātua with the mental health team at Counties Manukau District Health Board (CMDHB) — explains, the welcome is not just for Māori. This is a place of caring, he says, where manaakitanga is extended to all. Pointing to the rear wall, adorned with intricate patterns and framed photographs of significant people, Rawiri explains the presence of the sun carving.

“When I’m unwell, I see darkness. So hopefully that man up there is bringing some light.”

READ MORE:

*Part one: 'Dilapidated’ mental health units undermining care

*Part two: Overcrowded mental heath units breach torture convention

*Part three: Mental health units should provide more than ‘meds and beds’

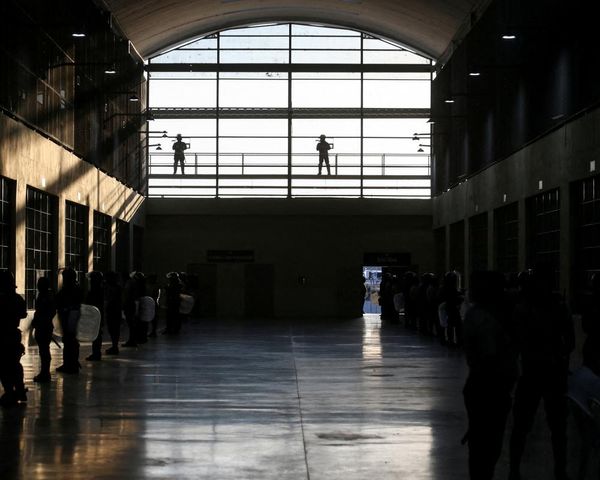

Newsroom visited the $64 million unit designed by Auckland architects Klein Ltd, in May. Designed around internal courtyards, the spacious wards and common areas were bathed in natural light, with easy access to fresh air. Just off the reception area, a high-ceilinged space with comfortable chairs and banks of windows, someone was playing basketball in one of the courtyards. The other outdoor spaces, built into the footprint of the building, featured native trees and planter boxes full of broccoli, chilli and other vegetables planted and tended by service users. The second and final stage of the unit, designed with input from mana whenua and tangata whaiora, opened last September. The te ao Māori influence is obvious, from the wharenui and wharekai through to the large pouwhenua in the central area, Te Manawa. New staff are given a workbook when they arrive on the unit to familiarise them with Te Whare Tapa Wha, a Māori model of health.

“This is like the new wave of inpatient design,” Dr Ian Soosey, the clinical director of mental health at CMDHB, says. “Most of the units around the country were built in the immediate aftermath of deinstitutionalisation and so were very much shaped by the thinking of that era.”

Tiaho Mai, on the other hand, was designed to send a message: this is a place of healing. Soosey believes the unit is far better for his patients, although he is quick to point out that the physical environment isn’t everything. As he rushes away, late to another meeting, he quips: “Once we start talking about this building, we talk a lot.”

It is easy to understand why. A post-implementation review, shown to the executive leadership team the week Newsroom visited, reveals a significant downturn in negative metrics compared to the old Tiaho Mai, a leaky facility built in the 1990s which was in a state of disrepair by the time it was decommissioned. In 2013/14, there were 43 reported physical and verbal assaults on staff. In the year to June 2020 in the new unit, this had dropped to 26. Restraint dropped from 173 to 134 incidents over the same period, with the downward trend continuing after the second stage opened last September. The number of self-harm/attempted suicides dropped from 13 incidents in 2013/14 to 10 in both the year to June 2019 and the year to June 2020. Most significantly, the number of people absconding went from 20-30 a month to just 0-5 a month in the year to June 2020; the DHB attributed this, in part, to the number of outdoor and indoor activities, something that was constrained in the old unit due to a lack of space.

Charles Tutagalevao, general manager of mental health and addictions at CMDHB, says the reduction in negative statistics is due to the enabling nature of the building, among other factors. Broad wooden desks on the wards encourage staff to do their work on the floor and engage with service users, a marked difference to the enclosed, glassed-off nurse stations in other units.

“I can’t describe how the spiritual dynamics and overall vibe work for me but they’re a big part of healing and without them the opposite is dark, crammed, oppressive, fearful and hopeless."

A business case to replace the old Tiaho Mai unit was approved in 2015. Stage one of the new building opened in 2018 and the unit was fully commissioned last September. Tutagalevao, a former mental health nurse, says the team is still figuring out how to get the best from the new space. But compared to the old unit, he says, it feels like a hotel.

Two weeks after the move into stage one, a roof in the leaky old building collapsed. The layout and condition of the building, described as ‘extreme end of life’, created an environment incompatible with a place of healing and recovery, the review said. Dr Gabriellle Jenkin, a sociologist at the University of Otago, Wellington, visited the decommissioned unit as part of her research examining the acute inpatient experience in New Zealand.

“That old one was the worst I’ve ever seen of any ward,” she says.

“It was dank, dark, threadbare and frightening.”

Staff and patient feedback about the new unit has been positive, Tutagalevao says. The flexible design means nurses can change the configuration by closing and opening up different spaces to separate groups of service users. The courtyards are internal to the building, so they aren’t fenced off and they don’t look like cages. Nurses can see across them to corridors on the other side, giving them improved line of sight, and the wards are designed around them, meaning the corridors mostly have rooms on just one side. People also have easier access to fresh air, light and nature.

Tiaho Mai has 52 beds in a mix of low and high dependency spaces, however there is scope to expand to 76 in response to demand and when staffing levels allow. The new unit also features more occupational therapy and intervention spaces, there is increased ability for partners to stay overnight and attend clinical sessions and there are dedicated psychologists who provide group and individual therapies.

“The whole place felt really safe and healing on a ‘spiritual’ level,” said a person who provided feedback included in the post-implementation review. They credited the kaumātua and iwi for making Tiaho Mai the space it was now. “I can’t describe how the spiritual dynamics and overall vibe work for me but they’re a big part of healing and without them the opposite is dark, crammed, oppressive, fearful and hopeless.

“I felt these in the old building as a service user.”

Chief Ombudsman Peter Boshier this week put out a press statement contrasting the condition of two mental health services housed in older buildings against Tiaho Mai, which his inspectors found to be modern and therapeutic. His report, following an inspection last June, still flagged issues — including criticisms that sensory rooms were small and hard to access and voluntary service users had no information about coming and going from the unit — however, overall the new building showed the positive impact of having a purpose-built facility.

"In my opinion it is a model for recovery and service user-centred care and the thoughtful design of the admission suite, in particular, is commendable,” Boshier said.

Of 24 mental health units assessed as part of a national stocktake of hospital infrastructure in 2019, Tiaho Mai was one of only three ranked ‘good’ against the relevant design criteria. Most were either ‘very poor’ or ‘poor’, which begs the question: how long will vulnerable service users have to wait to see more inpatient units like it?

Overhaul needed

In the past five years, service users have been treated in mental health units with reported issues including leaking, mould, fungal growth and pest and rodent infestations. As Newsroom revealed, vulnerable people have been looked after in stark, run-down and tired facilities with overcrowding, maintenance and cleanliness problems.

“I just think what it says about society is mental health is the lowest on the agenda,” Jenkin says.

Experts, service users and professional groups have all called for more investment to provide therapeutic, modern facilities and better resourcing for specialist mental health and addiction services. Instead, some groups have accused the Government of prioritising people with mild to moderate illness.

“To put it bluntly, it seems like they've been focused on the nice, warm and fuzzy end of things rather than the difficult areas,” says Helen Garrick, chair of the mental health nurses section of the New Zealand Nurses’ Organisation, a union.

While he believes unit culture is more important, Deputy Health and Disability Commissioner Kevin Allan, who visited many inpatient units in his former role as Mental Health Commissioner, says there does need to be investment in facilities.

“I think we do need to have a good, systematic way of improving facilities and continually updating, redesigning and replacing facilities that are beyond their use-by date.”

The Ministry of Health was unable to estimate how much it might cost to replace or improve all mental health facilities to ensure they were fit-for-purpose. However, it did provide the total budget allocation between 2015/16 and 2019/20: $472 million to refurbish or build new mental health facilities (this money has been promised, but not necessarily spent). The spend includes funding to address issues at some of the worst units: $30m for Hutt Valley DHB to replace its acute inpatient unit, Te Whare Ahuru, $18.8m for Tairāwhiti DHB to build a new unit, $25m for Lakes DHB to replace its more than 40-year-old facility, $30m for MidCentral to replace its inpatient unit, and $81.8m for Canterbury DHB to build new inpatient units at Hillmorton Hospital to house services currently stranded at Princess Margaret Hospital. Responding to the charge it had been overly focused on the “warm and fuzzy end of things”, the ministry referred to the Budget 2019 spend on specialist services, including $15m over four years for adult forensic mental health services and $19m for youth forensic services.

Ministry infrastructure deputy director-general Karen Mitchell said improving the state of mental health facilities was a key priority for the Government. As a result of common issues being identified with existing facilities, the health infrastructure unit within the ministry had set up a dedicated mental health infrastructure programme (MHIP). The MHIP, which would provide better engagement and support across a range of mental health building projects, was key to delivering on the Government’s priority, Mitchell said. The programme would produce a capital investment roadmap for acute mental health and addiction facilities across New Zealand.

“This includes building a clear picture of the current state and future service needs,” Mitchell said.

Last month, the facility design team, a recently established part of the health infrastructure unit, released draft design guidelines for acute adult inpatient mental health facilities. The ministry provided Newsroom with a copy of the new advice, which makes explicit many of the things we know create better outcomes.

The guidelines require facilities to incorporate Kaupapa Māori elements, environmental sustainability, accessibility and universal design and co-design, among others. In practice, this means doing things like having an appropriate strategy for engaging with Māori, incorporating local narratives and getting input from service users.

The new guidance, which applied to new builds and refurbishments, would be tested on current projects and updated in August 20201 based on feedback, Mitchell said.

MidCentral DHB (MDHB) is in the design phase for a new unit to replace Ward 21 at Palmerston North Hospital, a facility described as dangerous, cold, sterile and non-therapeutic by staff and in assessment reports. Vanessa Caldwell, mental health and addictions clinical executive for the DHB, said Ward 21 was “a classic case of not designing for the end user”. Service users were not bed-ridden like some people with physical health conditions — they needed activities, therapeutic programmes and places to meet with whānau. Caldwell said Ward 21, which was built like a regular hospital, didn’t take this into account.

Design of the new facility, by contrast, would be done in partnership with service users, iwi and community stakeholders. Architects appointed by the DHB started work in February, Caldwell said. Following the design process and once a builder was selected, construction would take about 18 months. Caldwell and others at MDHB had been to Tiaho Mai “to see what good looks like”, and planned to incorporate similar design features, such as a whare entrance. The new unit wouldn’t look like a hospital ward, she said. It would have light, colour and plenty of space.

“We want to create a space in which immediately people feel warm, welcome and safe.”

As well as Tiaho Mai, Boshier released two other Ombudsman inspection reports this week on mental health facilities at Palmerston North Hospital and Te Whare Ahuru, the acute inpatient unit in Hutt Valley. Both were unfit-for-purpose and Te Whare Ahuru (which had soiled carpets, graffiti and other cleanliness and maintenance issues) needed to be urgently upgraded, he said. Taken together, the three reports highlighted the stark differences in the condition of mental health facilities around New Zealand, and the positive impact well-designed, therapeutic units could have.

“Units such as these provide care for some of our most vulnerable and unwell people,” Boshier said in his media statement.

“It is crucial that they meet the standards of care and therapy we as a society expect.”

Want to share your inpatient experience? Email oli.lewis720@gmail.com

This project was funded by Nōku te Ao Like Minds, with support from the Mental Health Foundation

Where to get help:

1737, Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 or (09) 5222 999 within Auckland

Samaritans – 0800 726 666

Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO)

thelowdown.co.nz – or email team@thelowdown.co.nz or free text 5626

Anxiety New Zealand - 0800 ANXIETY (0800 269 4389)

Supporting Families in Mental Illness - 0800 732 825