Oldest evidence for math: 43,000-year-old scratch marks on a baboon bone found in Africa

Most famous equation: Einstein's E = mc2, which means energy is equal to mass times the speed of light squared.

Known digits of pi: More than 105 trillion digits

Digits of pi NASA uses for equations: 16 digits

Mathematics is the science that deals with the logic of shape, numbers and arrangement. Math is all around us, in everything we do. It describes the tiniest subatomic particles and the most massive structures in the universe, and it is crucial to many things in our daily lives, from how fast our hot cocoa cools to the path of a fastball as it arcs toward a batter. Math was invented as a field of study thousands of years ago, yet some of the simplest mathematical questions have never been answered.

5 fast facts about math

- There is no "biggest" number because numbers are infinite, meaning they go on forever. However, there are different sizes of infinities.

- No matter how long you stir a drink, after the liquid comes to rest, there will always be a point that ends up exactly where it started.

- Humans aren't the only species with number sense. Bees can count up to four and may even understand the concept of zero. And a famous parrot, named Alex, could add and subtract.

- The biggest prime number — that is, a number that can be divided only by itself and 1 — is 2136,279,841 – 1. To calculate this number, multiply 2 by itself 136,279,841 times, and then subtract 1.

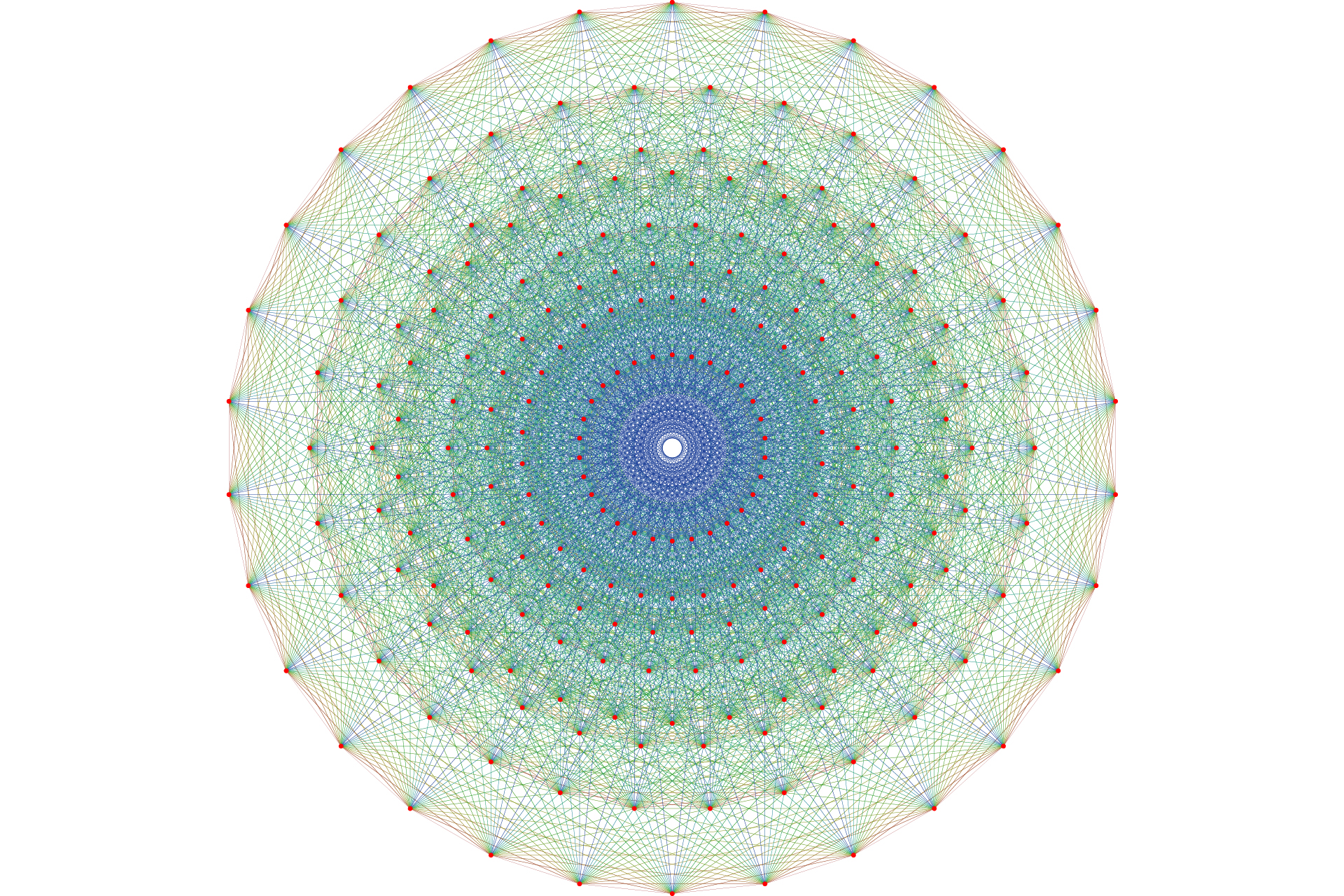

- Mathematicians think the most beautiful geometric object ever discovered is the E8 Polytope. They like it because the object, which exists in eight dimensions, is incredibly symmetrical

Everything you need to know about math

What is mathematics?

Mathematics is the study of numbers, quantity and space. In essence, it's the study of the relationships between things, and those relationships need to be figured out using logic and abstract reasoning. Counting is one of the earliest types of mathematical skills, but math is about much more than counting.

And while most people think numbers like 1, -3, or 3.14159 are the heart of math, a lot of math doesn't use any numbers at all — some is written with only letters, symbols or even drawings.

There are many types of math, from the simple arithmetic almost everyone learns in school to fields of study so tricky that only a few people on Earth understand them.

Arithmetic: Arithmetic is the type of math that deals with "operations," like addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. It also involves fractions, squares and square roots, and exponents.

Geometry and trigonometry: These fields of math study the relationship between lines, points, shapes, sizes, angles and distances. Geometry is what tells us the area of a circle and how big the Great Pyramids of Giza are, for example.

Algebra: In algebra, expressions describe relationships between numbers. Algebraic problems are equations that ask you to solve for unknown quantities, called variables. A simple algebraic equation is 5x - 5 = 10.

Statistics and probability: Statistics involves the mathematical tools used to understand large amounts of information, or data. Probability deals with how likely things are — it is the math of chance. Statistics and probability play a big role in engineering, business and medicine.

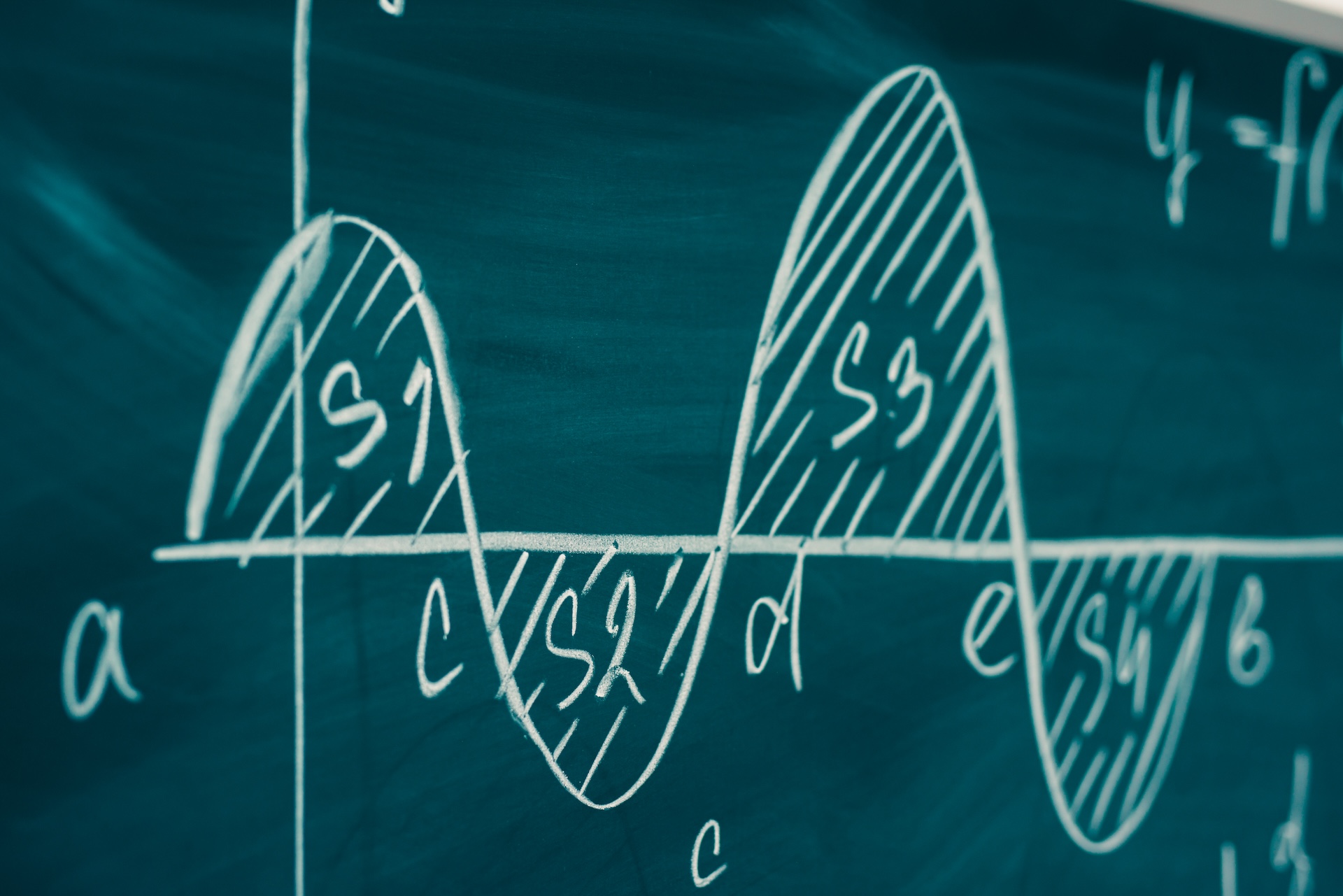

Calculus: Calculus is a more advanced branch of math that deals with derivatives and integrals. Derivatives describe how fast things change, while integrals find the area under a curve. Famous physicist Isaac Newton and his rival Gottfried Leibniz both separately developed calculus in the 1600s. Calculus is essential for physics.

Other types of advanced math include number theory, graph theory, topology, and complex analysis, which helps us understand "imaginary" numbers, or numbers that include the square root of negative one.

When was math invented?

No single person "discovered" or "invented" math, as humans likely always had some number sense and the ability to count. For instance, a 43,000-year-old baboon bone from southern Africa has notch marks that a person may have made to tally the 29 days of the month.

But the ancient Sumerians, who lived in what is now Iraq around 5,000 years ago, created the first known counting system that relied on base 60, which means you start a new digit or column after counting to 60. This is why we have 60 seconds in a minute and 60 minutes in an hour. The Sumerians also wrote simple algebraic equations, created multiplication tables, and calculated squares and square roots. We know this because they baked their calculations into clay tablets with a special type of writing called cuneiform.

Around the same time, the ancient Egyptians developed new ideas about geometry, — the math of shapes — and figured out how to measure the surface area and volume of those shapes.

The concept of zero as its own number emerged in ancient India more than 1,600 years ago. A document found in what is now Pakistan shows a little dot, which would eventually become the zero we know today.

Who invented algebra?

While some simple equations with variables have been around since the Sumerians, Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi is often considered the "father of algebra." This Persian mathematician and astronomer lived in what is now Iraq in the ninth century. In 820, he published a book about algebra called "Al-Jabr" — pronounced "all jabber" — which is how the discipline of algebra eventually got its name.

"Al-Jabr" introduced the idea of equations, along with some of their basic principles, such as that both sides of an equation should be equal. The book also showed several simple equation-solving techniques that people still use today, including subtracting a term from both sides of an equation or canceling out equal terms on either side of the equal sign.

Al-Khwarizmi also included solutions to certain polynomial equations, which are equations with a variable raised to a power. In particular, he provided general types of solutions to quadratic equations, which take the form ax2 + bx + c = 0, where x is the variable and a, b and c are numbers. Before Al-Khwarizmi came on the scene, people had only been able to solve these problems in tricky, confusing ways, using techniques that didn't hold for all types of problems.

What is a math proof?

We know 2 + 2 = 4. But how do we know that is true? It may seem obvious, but mathematicians need to prove that statements like these — and all mathematical relationships — are actually true.

They do this with a mathematical proof. Most math proofs use something called deductive reasoning, which lists the steps showing how a certain pattern or statement is true. Usually, it starts with something general that you already know is true, and works from there.

Even if this sounds easy, even relatively simple "conjectures" — ideas you think might be true — can be extremely tricky to prove.

Take the Collatz conjecture. Devised by German mathematician Lothar Collatz in the 1930s, it states that if you start with a positive integer (a whole number) and divide by 2 if it's even or multiply by 3 and add 1 if it's odd, you will eventually end up with the number 1.

You can test it on paper for many numbers and show that it holds. But how do we prove it holds for all integers? Mathematicians have been trying to solve the Collatz conjecture for decades, and it remains unsolved.

Some well-known proofs include one showing that pi is irrational, meaning it's a number that can't be written as a ratio of two whole numbers, and a proof of the Pythagorean theorem, which states how the lengths of the shorter sides of a triangle (a and b) are related to its longest side, or hypotenuse (c). This theorem — a2 + b2 = c2 — was stated around 2,500 years ago by Greek mathematician Pythagoras and proved by another Greek mathematician, Euclid, a couple hundred years later.

What's the hardest math problem?

There's not one hardest math problem, but there are many difficult, unsolved problems that mathematicians are eager to solve.

One organization has offered a $1 million reward to anyone who solves one of seven math problems. These questions, known as Millennium Prize Problems, are a set of seven unsolved problems that mathematicians agree are generally both difficult and important to crack.

One of these is to find a general solution to the Navier-Stokes equations, which describe how fluids flow. Only one Millennium Prize Problem, called the Poincaré conjecture, has been solved. The Poincaré conjecture had to do with how we define a sphere using a type of math known as topology, which looks at whether shapes become different when twisted, stretched or deformed.

Some of the hardest problems to prove are the easiest to explain. The Collatz conjecture is one example of this.

And sometimes, math proofs are so complicated that it can take years to figure out if they're right. For instance, in 2012, a mathematician claimed to solve something called the ABC conjecture. But the proof was 400 pages long, and there were only a handful of people in the world who could understand it — so it took several years to pick it apart. Mathematicians now say the proof probably has a mistake in it, but they had to spend several years to get to that conclusion.

Math pictures