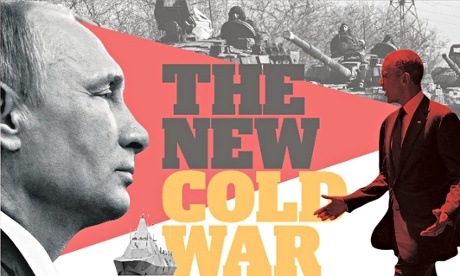

There are suggestions, at the start of 2015, that, after years being told that extreme ideologically-driven terrorists – "non-state actors" – posed the most serious security threat, we are now drifting towards a new cold war era, of conflicts between states.

While in the east, China and Japan are flexing their muscles, further west, Vladimir Putin is trying to show that Russia is again a military power to be reckoned with despite its serious economic problems.

Russia is developing a new cruise missile which the US says violates a 1987 nuclear treaty. The Obama administration is considering whether to respond by redeploying tactical nuclear cruise missiles in Europe.

Pentagon officials say they are concerned, too, about reports that Putin is planning to deploy short-range nuclear weapons in Crimea.

Meanwhile, Russia is expandng its fleet of submarines, stepping up naval patrols at a time Britain has no maritime patrol aircraft designed to reconnoitre and survey activities around UK waters.

As the Financial Times recently pointed out, ministers and officials in 2010 scrapped the planned of Nimrod MRA4 patrol aircraft despite a warning from the National Audit Office that such a move would have "an adverse effect on the protection of the strategic nuclear deterrent".

In an understandable but interesting argument, given the government's adamant defence of the continuing need for a Trident fleet of nuclear missile submarines, it appeared to believe such protection was no longer needed.

All this seems strange at a time of increasing globalisation, and interdependence, with the Russian economy in dire straits, national borders increasingly irrelevant in the west, notably in the EU, and ignored in the Middle East by the extreme jihadist group the Islamic State (Isis).

But perhaps this dichotomy is not so strange.

It is spelt out in "International Relations", a 150-page brilliant essay by Aberystwyth university's Ken Booth.

"There is no alternative to interdependence", he says. "Even for the most powerful states, dreams of political 'independence' and 'freedom' are like the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland: the smile lingers, but the reality has disappeared."

But Booth acknowledges there is a view that international relations will remain characterised by "war and the infantile rivalries of states, systematic injustice, and the countless forms of corrupt and corrupting power".

He adds that the continuing commitment of the UN Security Council permanent members and others to rest their 'ultimate' security on genocidal nuclear threats shows how far human society globally still has to go.

And he warns that the tides of globalisation, instead of washing away the state, might well provoke higher defences "as nationalist flag-wavers demand the exclusion of outsiders to protect the way of life of those who feel historically entitled to their homeland".

That is increasingly apparent, even in the EU, provoked in part by hostility to an elitist and undemocratic Brussels machine. (It should not be forgotten that the National Front is the largest French party in the European Parliament, where Ukip have more seats than British Conservatives or Labour.)

Booth is a follower of Immanuel Kant. The German political philosopher, he insists, was '"not dreamily utopian". At the centre of Kant's thinking about international relations was "the harmony of morality and politics, order through justice ...the need to think universally."

But in the other corner lies the shadow of Thomas Hobbes, who most famously declared that life in the state of nature is "nasty, brutish and short". Hobbes' philosophy is reflected in his claim that "during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every man".

The question is what tendency, the Kantian or Hobbesian, will gain the upper hand in 2015 and if it is the latter, as some commentators suggest, what that means for Britain's security and the future shape of its armed forces.