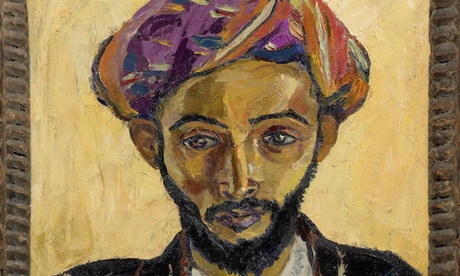

Hannah O’Leary knew right away that she was looking at something very special. The art specialist had been called to a flat in London to take a look at a painting. If its owners thought it was valuable, they had a funny way of showing it – they were using it as their kitchen noticeboard. Last week, it emerged that the artwork, which had postcards tucked into its ornate frame and had been draped with beaded HIV/Aids-awareness ribbons, was worth £1m. O’Leary, the South African art expert at Bonham’s auction house, recognised it immediately as an Irma Stern. “I knew that it was not just one of her paintings, but a very important one,” she says.

The painting, the Arab in Black, created in 1939 by the South African artist, turned out to have a fascinating history. In the 1950s it was donated to a charity auction raising funds to defend Nelson Mandela, and other ANC activists, as they were tried for treason. The people who bought the painting – the parents of the current owner – moved to the UK in the 70s, which is how it ended up in London. “[Stern] was South African-born to German parents and studied in Germany under Max Pechstein, moved in the expressionist circle in the 1910s, then took that training back to South Africa where she made it her own,” says O’Leary. “She was well respected in her own lifetime but since she passed away her stature has grown.” The owners weren’t clueless – they knew who Stern was and that it could be worth something. But they had no idea quite how much. “They were shocked and delighted, as anyone would be.”

Every so often a tale like this surfaces – the priceless painting found in the attic or down the back of the sofa (a family in Buffalo, New York supposedly found a Michelangelo stored behind their couch that may be worth $300m). One story, about a possible Jackson Pollock picked up for $5 at a thrift store, is so enthralling a film was made about it – the documentary Who the *$&% Is Jackson Pollock? followed former truck driver Teri Horton’s attempts to get it authenticated; the jury is still out whether or not it is the real deal, but she has said she won’t take less than $50m for it. In 1999, a painting bought from a furniture sale and hung on a wall in an Indiana home to cover up a hole was discovered to be by the American artist Martin Johnson Heade – it sold for $1.25m.

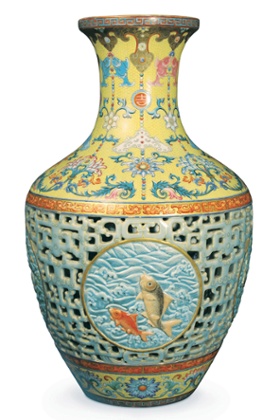

A Ming vase, believed to have been brought back from China in the 1930s by an adventurous relative, lived on a wobbly bookcase in Pinner – until it sold for £53m including VAT in 2010. But there were wrangles with the buyer, who failed to pay up, and a new buyer is thought to have paid around £25m for it in 2013. Others are not quite what they seem – a Renoir, apparently bought by a woman at a West Virginia flea market for $7 in 2010, was genuine, but her story wasn’t (friends of her late mother told papers the painting had hung in her house for years). The Renoir was valued at more than $100,000, but Ian Shapira, a Washington Post reporter, discovered that it had been reported missing from the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1951; the auction was stopped and last year a judge ordered that it be returned to the museum. Other finders are luckier – in 2012, Beth Feeback, an artist from North Carolina, picked up a large canvas at a charity shop for $9.99. She was going to paint over it, but a friend said she should look up the artist, which was on a label. It turned out to be by the abstract painter Ilya Bolotowsky, and sold for more than $27,000.

In 2012, a couple from Basingstoke, Jane Cordery and her partner James Ravenscroft, found a small, beautiful painting of an owl in their loft (Ravenscroft thought it had been in a box of things belonging to his mother). It was discovered to be a work by the pre-Raphaelite artist William James Webbe. “It’s a complete shock – I’ve never won anything beyond the odd thing from a tombola,” said Cordery before it was sold, when it had been valued at £70,000. It went on to sell for £589,250.

The story of a painting by the Hungarian artist Robert Bereny, which had been missing since the 1930s, is similarly incredible. In 2009, at Christmas time, the art historian Gergely Barki sat down to watch TV with his three-year-old daughter, and found the children’s film Stuart Little, the film about a mouse who gets adopted from an orphanage by a human family, then kidnapped. In the background of the family’s house, Barki spotted a painting of a woman with a 20s haircut, dressed in blue and asleep. He knew it was – Bereny’s Sleeping Lady with Black Vase, and he knew it was genuine – he had seen a photograph of it from 1928 in a museum archive, but since hardly anyone else had, he was almost certain it couldn’t be a copy.

“I knew this painting from a black-and-white photograph,” he says. “I couldn’t believe my eyes. I thought I was daydreaming.” This was before he had a TV that could pause and rewind, he says, so he sat glued to the screen for more glimpses. Luckily, he says, “there were many moments in the film where it appeared again so finally I realised it was the painting.”

Barki emailed the film’s production companies, then contacted as many crew members as he could. Finally, one of the set designers got in touch to say she had the painting in her house. He went to the US to see it. “It was absolutely amazing. It is a beautiful painting. It was a great moment.” The owner, he says, was “absolutely surprised” she had such a valuable painting (it had been acquired as a prop from an antiques shop for a few hundred dollars, and she had later bought it from the production company).

She sold the painting to a collector, who auctioned it for €229,500 in December 2014. Since then, Barki has been on the constant lookout for other works. “I hope more will pop out again,” he says.

So how often are miraculous masterpieces found? “A story like this is really very rare,” says O’Leary of the Irma Stern find. “The internet has changed everything – if you’re left a painting or you buy one in a shop, you can Google the artist’s name and find out pretty quickly whether it’s worth something.” In her career, she has had other examples of people who bought paintings at car boot sales, then found them to be worth quite a lot – but nothing like £1m.

“For every truly important work that turns up, there are a lot of hopefuls,” says Nicholas Eastaugh, scientist, art historian and director at Art Analysis & Research, which authenticates works for clients including auction houses. “A lot of people are on the lookout for something tucked away in their attic or on a grandparent’s wall.” People bring works to his lab, which offers tests including scans and analysis of pigments, but he gently tries to steer people away if he thinks there isn’t much chance of finding something. He once had to break the news to a client that a painting they thought was by Rembrandt wasn’t. Is it awful having to disappoint people? “If someone has put all their hopes on something, it can be difficult for them to accept,” he says. “We go through the stages of grief, as it were.” But when he does find something, it’s worth it: “To share in that process is exciting. These new discoveries make our day, too.”